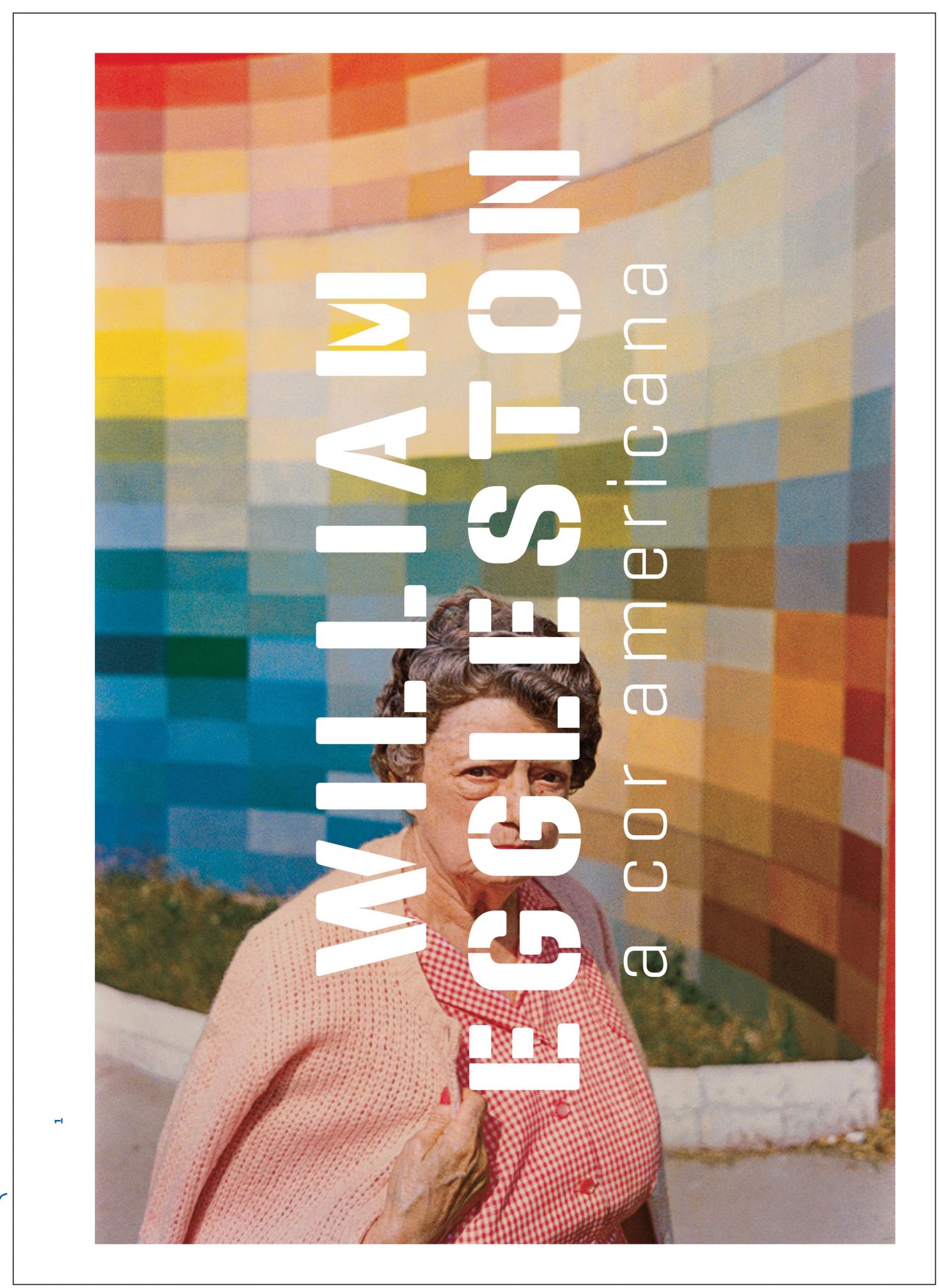

“William Eggleston, American Color”, exhibition at IMS-Rio de Janeiro

Publicado em: 27 de fevereiro de 2015from the portfolio The Seventies: volume 2, 1972

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________

William Eggleston, American Color

March 14th to June 28th, 2015

Curated by Thyago Nogueira

opening featuring the artist’s presence,

March 14th, Saturday, 5 pm

screening of William Eggleston in the Real World (2006), a documentary film by Michael Almereyda, and the launch of the catalogue

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Starting March 14th, Instituto Moreira Salles/Rio de Janeiro presents William Eggleston, American Color, the first large solo exhibition in South America dedicated to American photographer William Eggleston. The exhibit will feature around 170 original photos coming from famous collections including the Museum of Modern Art in New York (MoMA), the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston (MFAH), Eggleston Artistic Trust, Cheim & Read and Victoria Miro galleries.

William Eggleston is one of the most important artists in the history of photography. His vibrant and most famous images depict day-to-day life in small cities and suburbs of the American south, constructing an inventory of American culture in the 1960s and ‘70s. Eggleston opened new ground for photography by combining a focus on the symbols of modernization (roads, cars, supermarkets, billboards, shopping malls, parking lots, fashion), a particular use of color saturation and a diaristic approach while documenting friends, family members and anonymous characters.

William Eggleston first found success in 1976, when the influential John Szarkowski, at the time the director of the photography department at MoMA, organized an exhibition of his color photos at the institution. Up until then, black and white photography was the norm. The exhibition, which presented ordinary scenes, a freedom in formal composition and the seductive nature of color – at the time most often seen in amateur and commercial photography–, became the subject of an intense debate in the photography community, and was subjected to harsh criticism. Over the years, however, the exhibition came to be seen as a milestone.

Today, Eggleston’s images are among the most celebrated and influential in 20th century photography, with a wide variety of admirers: from photographer Nan Goldin and musician David Byrne to filmmaker Wim Wenders and Brazilian artist Karim Aïnouz. Such movies as Gus Van Sant’s Elephant were notoriously inspired by the photographer’s visual world. Both Van Sant and David Byrne have invited Eggleston to collaborate on projects.

William Eggleston, American Color is one of the biggest exhibitions ever done on the photographer and will bring to Brazil for the first time an extensive selection of works from 1960s and ‘70s, considered to be Eggleston’s golden years. One of the rooms will feature many of the photos included in the legendary 1976 exhibition at MoMA. Two other rooms will present the famous portfolio Los Alamos, which resulted from a series of road trips around the Mississippi Delta and all the way to California from 1965 to 1974.

The photos on display will include over 150 rare and delicate photographs made through dye-transfer, a near-extinct printing technique, which became the artist’s trademark for allowing him a precise control of color and intense saturation. To those who are already familiar with Eggleston’s work, the exhibition will also feature lesser-known, but still important works from the period. Among them, the formidable set of portraits made on bars and streets with a large format camera in 1974 and known as 5×7, in reference to the size of the film used. A set of five black and white photos, made before Eggleston embraced color definitively, will also be on display. The experimental film Stranded in Canton, shot in black and white in 1973 and 1974, with improvisations, performances and intimate footage of family members and friends in the bars of New Orleans will also be on view.

William Eggleston, American Color was curated by Thyago Nogueira, editor of the ZUM magazine and coordinator of contemporary photography for the IMS. The exhibition design was created by Martin Corullon of the firm Metro Associados, and the visual identity was designed by graphic artist Luciana Facchini.

***

READ THE TEXT BY CURATOR THYAGO NOGUEIRA, PUBLISHED AT THE EXHIBITION CATALOGUE:

William Eggleston: An Extraordinary Puzzle

Thyago Nogueira

I’ve always hated that technology is not yet here to record our dreams.

William Eggleston

Sporting robust curves and looking rather worn-out, a white and green tricycle stands out in a suburban American landscape, with its typical rows of perfectly-aligned bungalows distinguishable only by the mailboxes and the cars in the garage. Taken in Memphis in 1971, the photo is printed on the cover of the catalogue book known as William Eggleston’s Guide, published by the Museum of Modern Art in New York on the occasion of the photographer’s first major solo exhibition. By positioning the camera on the ground, Eggleston offers the viewer a child’s perspective and suggests that the tricycle will guide us in our journey.

The small catalogue brings together street scenes, landscapes, indoor scenes and portraits taken in the photographer’s native region, an area in southern United States that covers the western part of the state of Tennessee and follows the Mississippi river towards New Orleans. It was John Szarkowski’s idea to call the catalogue a guide. At the time, he was the director of MoMA’s department of photography, where the exhibition opened on 25th May 1976. The title was a reference to the famous Michelin Guide, created at the beginning of the 20th Century by the French tire company to stimulate the car industry, an ironic wink that proposed an excursion through an area featuring few notable tourist attractions and even fewer tourists.

BACKGROUND

Eggleston was born in 1939 in Memphis, Tennessee, but soon after moved to his maternal grandfather’s house in the city of Summer, Mississippi, because his father, who was in the navy, was forced to spend extended periods of time away from home. A descendant of a family who for at least the last two generations dedicated themselves to the the cotton industry, Eggleston grew up in a region dominated by old plantations, floodplains and the swampy streams called bayous, peppered with small urban nodes and intersected by a growing network of roads. It is a region of the United States that, throughout the 1960s, when Eggleston was growing up, still coped with the scars of its slavery past, divided between intense racial conflicts and the emerging middle classes, which were interested in the new standards of consumerism. Those were the days of Elvis Presley and the Vietnam War, of J.F. Kennedy (killed in Dallas in 1963) and Martin Luther King (killed in Memphis in 1968).

Eggleston first delved into photography when he was in college. In 1957, as a Vanderbilt University undergraduate, he bought his first camera and began to work intensely in taking pictures. When transferred to the University of Mississippi in Oxford two years later, Eggleston came into contact with the work of Henri Cartier-Bresson and Walker Evans. It is likely that Cartier-Bresson’s work freed Eggleston from his photographic constraints. The French photographer’s candid street shots proved it possible to condense complex movements in a single image, inspired by ordinary themes. Quite different from the technical and compositional rigidity of photographers such as Ansel Adams, who was the reference point in fine art photography. Cunning and informality became photography’s inextricable ingredients.

In Evans’s photos, Eggleston must have discovered the unassuming elegance of the plain and balanced frontal framing. The affinity must have also been thematic. In 1936, Evans and the writer James Agee were sent by Fortune magazine to spend time among cotton sharecroppers in southern United States, for a reportage on the effects of the Great Depression. The article, which steered away from traditional journalistic features, took five years to get published, but several of the photographs taken in Alabama, Mississippi and Tennessee were included in Evans’s American Photographs (1938), a book Eggleston read in college. The storefront of a New Orleans barbershop, the patterns created by torn posters or a typical automobile repair shop are just a few of Evans’s images that seem to have resurfaced, years later, in Eggleston’s work. Evans was an intellectual photographer, casting a rather uncommonly detached and refined gaze on southern decadence.

IN BLACK AND WHITE

Eggleston did not graduate but college gave him the opportunity to experiment with several artistic practices. His friend the painter Tom Young introduced him to abstract expressionism. By this time, the young Eggleston had already transformed black and white photography into a regular practice, and he developed his photos himself. His first shots emulated those of the masters who inspired him, but the period of intense work with a 35 mm camera between 1960 and 1965 was a game changer.

“I couldn’t imagine doing anything more than making a perfect fake Cartier-Bresson. And finally, I have succeeded. But there comes a time — and it has to have something to do with seeking my roots and coming to Memphis —, because then I didn’t have those mentors, a time when I had to face the fact that what I had to do was go out in search of unknown landscapes. What was new at that time were shopping centers − so I took photos of them.”

In the following years, Eggleston focused on the daily life of small towns in southern United States, the strange and familiar world that surrounded him. He took photos of everything: convenience stores and diners, offices and workshops, supermarkets and parking lots, as well as his family, friends and whoever he met along the way. Agricultural mechanization and accelerated industrialization laid the ground for a new urban class to emerge. The car industry was modernizing, driving vehicle prices down and ensuring that, wherever there was a highway, there would be cars. Neighborhood shops were replaced by gigantic strip malls, which offered hundreds of products and catered to several urban cores. Social life drained away from the city’s main squares to the shopping centers off the highways, with their constellation of shops, restaurants and movie theatres. Traditions were modernized, and fashion underwent changes with new cuts and fabrics. An everyday life that had seemed stagnant was gaining a new lease of life. Wheel caps shone, trendy hairstyles emerged, merchandise flashed and consumerism bloomed. A world of lights, sparkles and… colors. Just what photography had been missing.

LIFE IN COLOR

Around 1965, Eggleston began to experiment with color film, which had rarely been used in fine arts and was more commonly found in advertising and amateur photography.

“What I set out to do was produce some color pictures that were completely satisfying, that had everything, starting with composition. My first tries were ridiculous. I got some snapshots back and I hadn’t exposed them properly; they were awful. I threw them away. Composition was probably correct, but it was lost in the … dismal technical failure. I’d assumed I could do in color what I could do in black and white, and I got a swift, harsh lesson. All bones bared. But it had to be.

“Then one night I stayed up figuring out what I was gonna do the next day, which was go to Montesi’s, the big supermarket on Madison Avenue in Memphis. It seemed a good place to try things out. I had this new exposure system in mind, of overexposing the film so all the colors would be there. And by God, it all worked. Just overnight. The first frame, I remember, was a guy pushing grocery carts. Some kind of pimply, freckle-faced guy in the late sunlight (p.3). Pretty fine picture, actually.”

The image of the supermarket assistant already hints towards questions that will become central to his work. The attentive gaze upon the everyday life in small towns in southern United States; the interest in prosaic themes and in the ordinary man; the new forms of social interaction engendered by changing customs and consumption habits and by urban decentralization with its related mass production of cars and networks of highways; and, of course, the seduction of colors and bright lights offered by the world of commodities. The yellow light, which highlights the angelic profile of the young boy and the metal of the shopping cart lends an air of sophistication to what was previously regarded as only ordinary.

LOS ALAMOS

The image of the supermarket is the keystone of Eggleston’s first large series which would later be known as Los Alamos. Taken entirely with color negative film, Los Alamos is composed of some 2,200 photos taken in the photographer’s native region and during his trips, solo or in the company of friends, to New Orleans, Las Vegas and Southern California. The photos were taken during two time periods: between 1965 and 1968 and between 1972 and 1974.

Seen together, they make up anthem of sorts for the American roads which could be an epigraph for musician David Byrne’s line in the film True Stories (1986): “Highways are the cathedrals of our time”.

Most of Eggleston’s images are organized around a noteworthy central element related to color, scale or visual complexity, as in the huge hamburger billboard against the blue sky (p. 95), the ruffled dwarf palm sprouting from the corner of a garden (p. 105), and the elegant grey-haired woman seen from her back (p. 101). In some images, the photographer comes so close to his subjects that all one can see is a fragment, as if he just wanted to show us their colors, surface and texture, a graphic result that could be linked to his interest in abstract expressionism. The way in which Eggleston works, composing a panorama of fragments of Americana, reminds one of a metonymic construction, addressing everything by representing its parts.

The images’ color is intense and the contrast high, with its greens, reds and yellows enhanced by the clear blue sky or the golden light of dusk. Even when an old lady frowns, the colors evoke a happy, sunny world. But a closer look also reveals a tinge of precariousness. The red Coca-Cola freezer is worn-out in a state very unlike that displayed in advertisement (p. 18); the nicely-made poster for ice creams displays glaring spelling mistakes (p. 20); a person who should be having fun at an arcade is caught gazing off into the distance (p. 103); and many of the shiny awnings and façades seem damaged. With his themes and colors, Eggleston adds an ambiguous layer to the strange mix of optimism and pessimism that permeated American society. These were times of glowing consumerism and opaque decadence.

The framing of the images is either frontal or skewed at angles. Sometimes the cuts are dry, abrupt and sudden and the close-ups so large that it is difficult to make out the context. It is as if Eggleston was roaming and tripped over a theme and had instinctively taken a picture, before getting the chance to adjust the scene’s composition. Garry Winogrand once said: “I photograph to see what the world looks like in photographs”. Eggleston seems to follow a similar intuition. Take photos first, recognize later. It isn’t that different from someone going into the woods to hunt partridges who at the slightest sound turns around and shoots. It is quick and precise work, which Eggleston himself compared to playing the piano, a passion he has had since his childhood.

In some cases, Eggleston seems so obsessed with a specific subject that he ignores what is happening around it. Perhaps this helps to explain the strange framing of the sign above a Laundromat − at the center of which stands a thin fluorescent lamp (p. 117) − or the awkward framing of a locker room with tiled walls, in which the photographer focuses on a pair of hangers (p. 107). The hard cut produces an unexpected composition that adds mystery and fascination to the images. It is as if by focusing on the ‘objects’ of modernity, Eggleston created photographic ready-mades.

The way of photographing is curiously described by the British author Geoff Dyer in his book The Ongoing Moment (2005): “Eggleston’s photographs look like they were taken by a Martian who lost the ticket for his flight home and ended up working at a gun shop in a small town near Memphis. On the weekends he searched for that lost ticket — it must be somewhere – with a haphazard thoroughness that confounds established methods of investigation.”

In order to understand Eggleston’s photos, it is also necessary to take into account his great interest in amateur photography with its abundance of banal topics and random compositions. The photographer himself remembers how, at the end of the 1960s, he used to visit a friend who worked in an automatic film-processing lab: “I began to see those images come out – they came out in long strips – and I thought that the majority of them were an accident. Some of them were absolutely beautiful. I started spending all night long admiring those strips of photos.”

His awareness of the seductive power of the color image, his interest in mass culture, in advertisement and in an almost kitsch world also brought him closer to the Pop artists of the time.

Eggleston – known as Bill by his friends – mostly kept his distance from the major art centers. In his last interviews, he was as monosyllabic as his photographs. He avoids talking about his work and does not care much about what others have to say about him. According to Eggleston, words and images are two distinct languages: “One has nothing to do with the other”, he affirms. “It’s possible to like art and appreciate it, but not to talk about it.” Eggleston does not like to title his images (titles “can distract too much”) and even when interested in a subject, he only dedicates one or two clicks to it. “It is very confusing afterwards if you have a strip of six images and you have to pick one.” he explains.

SLIDES

During the years he photographed with color negative film, Eggleston produced his prints in automatic processing photo shops, and he would edit his work with them and then show them to his friends. However, the automatic process permitted little control over the final result and, with time, the color of the images would fade. Automatic color prints were a practical and cheap solution, but limited if compared to the control offered by black and white photographs that allowed the photographer to make adjustments in the laboratory.

In 1969, perhaps unhappy with the results, Eggleston put aside the negatives and embraced slides. Slides gave his work a new boost, since the technology that permitted the production of a positive image on film also provided more defined colors. From 1969 to 1974, he made close to five thousand color slides. Little by little, chance also appeared to gain strength in his images. Eggleston began to photograph without looking through the viewfinder, placing the camera on the ground, leaving it at waist height or raising his arms over his head, as in the photo of the tricycle (p. 137) or in Greenwood, Mississippi, 1973 (p. 135).

During that period, the photographer took another important technical step. Slides generated a positive image that could be seen directly without the need of printed copies. On the light table or while projecting his slides on his living room’s walls, Eggleston would get his friends together to show his work during fun soirées, very often with the photographer at the piano. However, he still needed printed copies so that the images could be circulated and sold.

Around 1972, Eggleston adopted the color printing process know as dye-transfer. A common process in fashion and advertisement photography, dye-transfer was costly and laborious. However, the technique permitted the photographer to individually control the colors and produce intense saturation. The images gained body and came to life. It is not surprising that one of the first prints using dye-transfer was Greenwood, Mississippi, The red of the roof gained an extraordinary intensity, which reminded one of Henri Matisse’s statement: “A certain blue enters your soul. A certain red affects your blood pressure”!

EXPANSION

Between 1973 and 1974, Eggleston added two important exceptions to his work: the video footage that eventually became Stranded in Canton (2005) and the large format portraits from the 5 x 7 inch series.

Influenced by American Direct Cinema, Eggleston recorded his family and nights out with friends in black and white, using adapted portable cameras sensitive to infrared light. In a mixture of irreverence and intimacy, the characters pull all-nighters of declamations, improvisations and binge drinking. The title refers to an imaginary place called Canton, where you can “smoke marijuana, hang out naked and where you never need a passport”, one character explains.

The second exception was a group of posed portraits, produced with a large format camera that enabled him to attain a level of detail similar to old studio portraits. The photographer took the camera and a flash to bars and recorded strangers and acquaintances. Despite being faced with bulky, complex equipment, the characters seem oddly at ease, facing the camera or absorbed in their own world. Focused and well defined, the images make up a gallery of American types that evoke traditional yearbooks.

STRANGE AND FAMILIAR

A big fan of guns and cars, Eggleston never needed a steady job. He was known for his bohemian lifestyle, his evenings regularly filled with music and booze. During the period that coincides with the adoption of slides and the birth of his children − William Joseph iii (1967), Andra (1971) and Winston (1973) –, Eggleston began to make photographs that displayed a subtle, but notable, difference.

Gradually the ‘on the road’ spirit gave way to more familiar landscapes. A larger number of images of Memphis and Sumner, where Eggleston spent a large portion of his life, appeared. The street scenes and images of anonymous pedestrians began to make way for people in their homes, seated in their living-room armchairs, at the piano or in bed. Familiar faces appeared in the images, and just by glancing at them it was possible to spot his friends, children, and other members of his family. Even the sharp close-up framings seemed to alternate with open panoramas that offered ampler views of the scene, space or region. A more nuanced vision was added to the apparent restlessness of his early years. The stark colors and strident saturation were also tapered down. Photos of cloudy days, nightscapes and purple-tinged late afternoons show up more often.

In his classic “American Photography in the 1970s”, Lewis Baltz explains that the period was marked by intense public funding and the emergence of chairs of photography at the universities. The innumerous museums, built in the previous decade, also saw photography as a cheap and fast way to build collections and attract the public. In the 1970s, photography portfolios and books by artists flourished, as a result of funding and an emerging group of collectors, students, and experts. In 1975, the George Eastman House, in Rochester, shocked the public with the exhibition New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape, with Stephen Shore’s color images and Robert Adam’s and Lewis Baltz’s black and white photos, among others.

All of this was at stake in 1976 when John Szarkowski inaugurated, at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the exhibition Photographs, including 75 of Eggleston’s images, and published the small Guide. At 36, the young artist from Memphis made his mark on the cosmopolitan city.

In a note sent to Szarkowski in July of that year, the influential art critic Clement Greenberg thanked him for the catalogue while at the same time displaying the typical mistrust that hovered over color photographs: “The photos are eye-catching, and so is your essay. Once again, I am obliged to notice that everything is possible in art – not that I wouldn’t have thought that good color photography was possible, but it appeared improbable, only occurring by accident. Yes, I have seen many color photos that turned out to be good out of accident (I myself made two), but, because they were by accident, they did not add up. Those of Eggleston add up, and accidental is the last thing I would call them.” Eggleston was elaborating a new visual vocabulary for the United States.

Comprised of only 48 images and more intimate than most of his work, William Eggleston’s Guide became one of the most influential books in the history of photography. His fame can be accredited to the perfect combination of intimacy and mystery, proximity and elusiveness of each image, but also to their general narrative coherence, constructed through careful editing. Like an invitation to that world, the book opens with the door of a house, decorated with a plastic wreath touched by the light of dawn. Throughout the following 47 images, the photographer guides his viewers through towns in Tennessee, Mississippi, Louisiana and Alabama. Viewers enter and exit homes, walk through unknown backyards, pass people in the street, share intimate moments with friends, neighbors and family, while simultaneously being introduced to the vastness of the southern landscape. The book feels like a long day, filled with odd or ordinary events. Gradually, nightfall takes hold of the images, presenting a sequence of interiors and nightscapes, where characters circulate, that suggest the passing of time, in a reminiscence of boredom and loneliness.

AMERICAN COLOR

William Eggleston: American Color brings together the photographer’s best work, shot between 1960 and 1974. For the first time, the show brings to Brazil the famous series presented at the MoMA in 1976, along with other pictures from that period, offering a comprehensive overview of his production. It was not until after 2000, when the images published in the Guide became widely consecrated, that the black and white photos, the series Los Alamos, the 5 x 7 portraits and his video experiment began to get the attention they deserved. Almost forty years after his triumphant debut into the world of art, Eggleston’s relevance to the history of photography is greater than ever.

With his unique syntax, Eggleston opened new paths to color photography. His strange jigsaw puzzle of pieces and fragments, black and white and color photographs and videos, enriched people’s understanding of the times they were living. His work became synonymous with the American way of life and offered an indirect comment on the effects of mass culture and consumerism, of obsolescence and alienation. Eggleston’s interest in everyday life, his belief in the fascination of the image and his world of colors and themes, composed an extraordinary symphony that continues to be assimilated by generations of amateurs and artists.

|

William Eggleston, a cor americana Thyago Nogueira, ed. Shortlisted for the 2015 Paris Photo-Aperture Foundation Photobook AwardsWith texts by Thyago Nogueira, David Byrne, Geoff Dyer, Richard Woodward & John Szarkowski (in Portuguese) Format: 22,5 x 31cm Pages: 156 ISBN: 978-85-8346-021-3 Buy here |

About the photographer

William Eggleston was born in Memphis, Tennessee in 1939. In 1976, MoMA/NY presented the exhibition Photographs, which set Eggleston reputation as one of the most important photographers of 20th Century. Eggleston won the prestigious Hasselblad Award in 1998 and an Infinity Award from the International Center of Photography in 2004. His work has been the object of numerous books, including William Eggleston´s Guide (1976), Chromes (2011) and Los Alamos revisited (2012). In 2008, the Whitney Museum of American Art held one of the largest retrospectives of his work. In 2002, dOCUMENTA in Kassel displayed a selection of his photos. The Eggleston Artistic Trust, which preserves and disseminates his work, was founded in 1992 in Memphis, where the artist lives and works.

Events

In the lectures, given among the exhibition’s works, thinkers of photography are going to talk about William Eggleston’s work (in Portuguese):

April 10th, Friday, 5pm – Nelson Brissac Peixoto (PUC-SP)

May 13th, Wednesday, 5pm – Antonio Fatorelli (ECO-UFRJ)

exhibition

William Eggleston, American Color

opening featuring the artist’s presence

March 14th, Saturday, 5pm.

screening of William Eggleston in the Real World (2006), a documentary film by Michael Almereyda, and the launch of the catalogue

visitation

March 14th to June 28th

Tuesday to Sunday, from 11am to 8pm

Instituto Moreira Salles – Rio de Janeiro

Rua Marquês de São Vicente, 476, Gávea

Phone: (21) 3284-7400/ (21) 3206-2500

Sumner, Mississippi, Cassidy Bayou in the background, c. 1969 // from William Eggleston’s Guide, 1976

IMAGES © Eggleston Artistic Trust. Courtesy Cheim & Read, New York.

Tags: IMS Exhibitions