Between Heaven and Hell

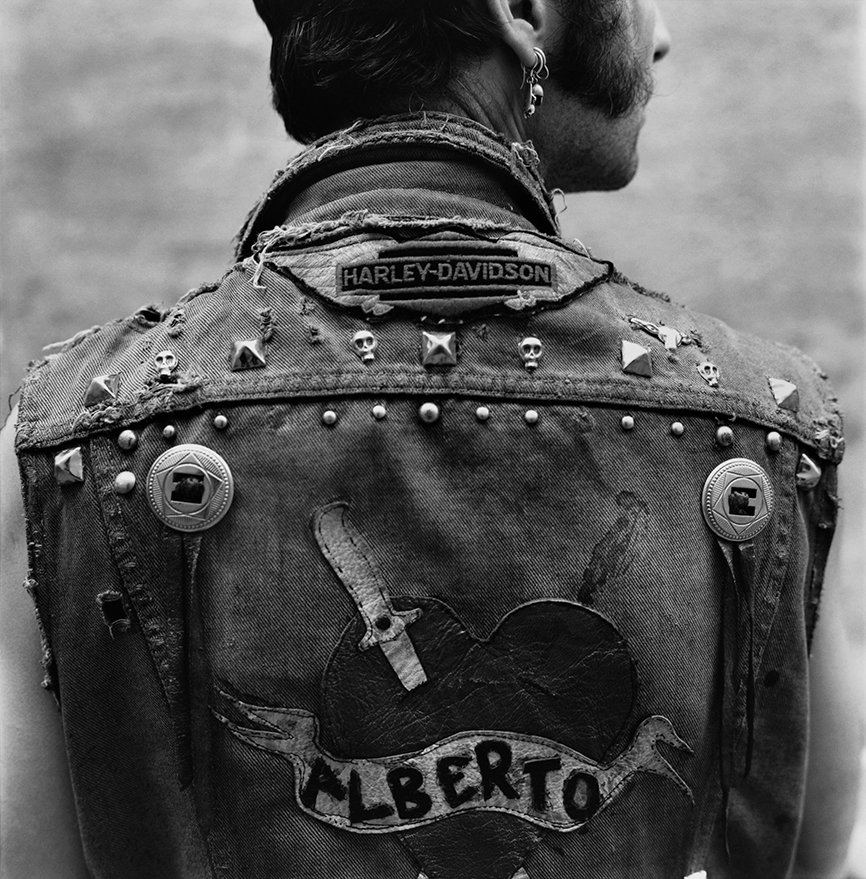

Publicado em: 22 de January de 2014An eternal adventurer, the Spanish photographer ALBERTO GARCÍA-ALIX, who recorded the rebellious years of la movida madrileña, presents his new road companions

Motorcycles arrived before photography in Alberto García-Alix’s life. He was 12 years old, not a sign of his trademark side-whiskers yet to be seen, when his parents gave him a yellow Ducati. The engine was pretty feeble but those 50ccs seem to have had a more powerful impact on the future photographer’s eye than other elements of his life: the powerful women, the tattoos, the heroin, the rock’n’roll or the Cuba Libres mixed with Negrita rum.

“On a cycle the frame is gone,” wrote the American Robert M. Pirsig in his book Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance (1974). The motocyclist is in the scene, not just watching it. Life on two wheels: the real and constant possibility of a fall; overcoming the powerful blast in your face; the tarmac flowing fast under your feet; unexpected curves. That’s how it is on the road when you’re astride a motorcycle, and that’s what García-Alix’s photographs are like.

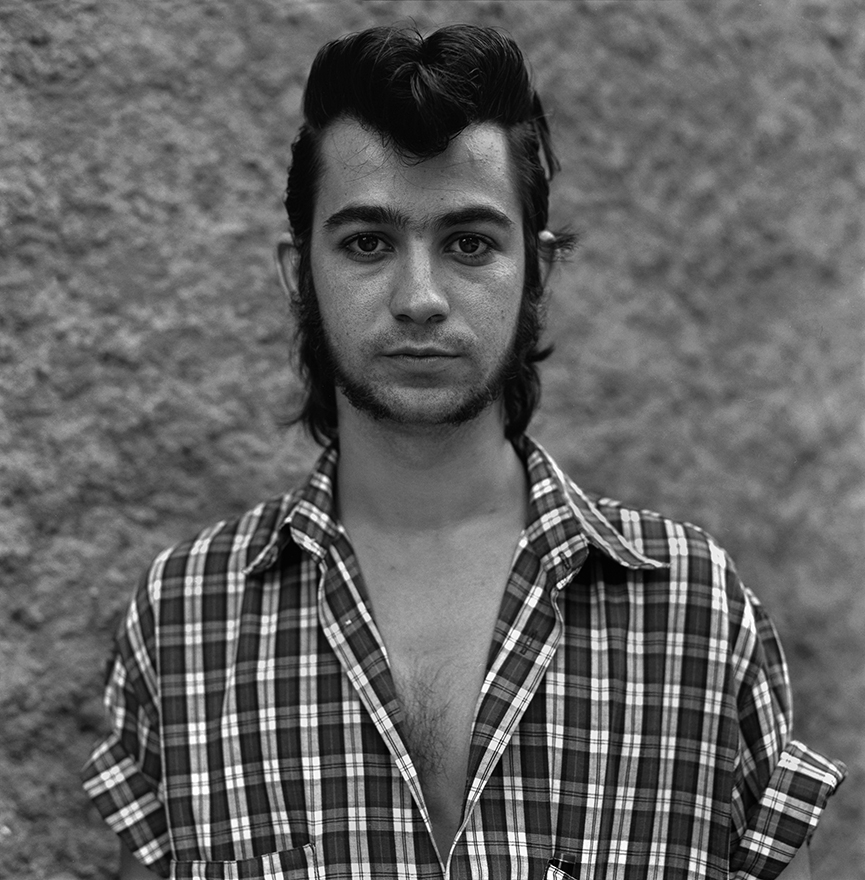

His story starts in 1956 in his birthplace, León – 338 km northwest of the Spanish capital. His father (appropriately an ophthalmologist) moved to Madrid with his family in the 1960s. Photography began by chance, García-Alix repeats whenever he can, frequently saying how he is self-taught. In 1975, a camera “fell into his hands” – as he says – the same year that a new political horizon “fell into Spanish hands,” with the death of Generalissimo Franco.

That moment was rapidly followed by the opening of the cultural floodgates: the movida madrileña (Madrid Movement), that moment of bohemian and cultural effervescence that swept over the Spanish capital in the late 1970s and early 1980s. García-Alix surfed on the wave of this trend along with many others, such as the film director Pedro Almodóvar, the punk-rock singer Alaska, the painter/musician/ does everything Fabio McNamara and the illustrator Ceesepe, who joined the photographer in the Cascorro Factory collective.

García-Alix had a motorbike, a camera – and not a lot more. He rode the city from one bar to another, from one party to the next, until he woke up on a sofa somewhere. When he managed to put some pesetas in his pockets, he bought some rolls of 35mm film. And so, from time to time, the clothes line in his house sported portraits of strange faces, drying alongside underpants and socks.

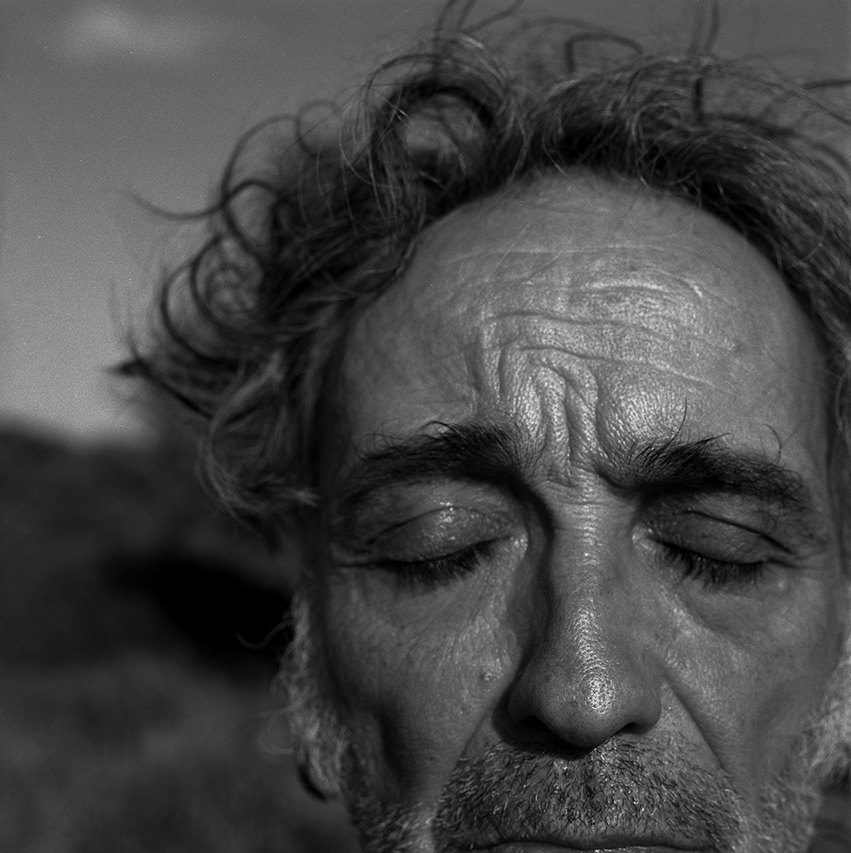

Montserrat, 2005

It is strange, but at the same time perhaps not, to imagine these photographs in such an environment. 57 year-old García-Alix is nowadays one of Spain’s most celebrated photographers, an artist of European dimensions. His images are at home as much in a scullery as they are in the Reina Sofia Museum, that great Spanish temple to contemporary art, which put on a retrospective of his work in 2008 with more than 250 photos.

The name of the exhibition, De donde no se vuelve [from where there is no return], is the title of one of García-Alix’s most introspective works, which was published in a collective work of almost 300 pages entitled Morreremos mirando [we will die looking], in 2008. Written as an essay with some poetic touches and afterwards reconceived as a film script (García-Alix becoming fascinated by film), the text speaks in various semantic levels of the experience of losing oneself. It speaks as much of the experience of becoming involved in a new land – as he did when he systematically photographed what was to him the unknown life of the villages of China at the end of the last decade – as of the concrete, irreversible losses in life.

“Night and day, we feed a demon through our veins. Years when the pupils of our eyes demonstrate the emptiness of our smiles, with our heart in our mouths. We anaesthetise both love and pain,” he wrote of his long, intense and difficult experience with heroin. “Heaven was found five or six blocks away from Madrid,” he notes, without mentioning the distance to hell. Willy, his brother, was the first in the group to die of an overdose, aged 25. Many others followed the same path to an “immense cemetery,” including his companion Teresa – Tere.

People, places, situations, passions passed by and moved on, with no return. But García-Alix had a camera and what he calls the “will to meet.” “A portrait is an encounter between human beings which bears the happiness and the pain of being transient,” he said when receiving the important Spanish National Photography Prize in 1999. “This encounter is memory. Once the shutter is clicked, the subject is a prisoner in the image. It’s already not the present, it’s the past. We’re already not who we are, we’re who we were.”

And the portraits are not in scarce supply. Over four decades of clicking, García-Alix has taken more than 100,000 photographs, always using fi lm (“digital is too false, beauty is in the imperfections”). It is an almost infinite universe of solitary figures, most of them in black and white: transexuals, tatooed people of all sorts (“to enter heaven, thou must be tatooed”), people with squints, porno actresses carefully displaying their attractions with a gynaecologist’s dexterity, injured men, one with a bruised eye (“he was hit on New Year’s Eve,” says the caption). Colour is rarely used, and there are only a handful (and that hand is well supplied with skull rings) of smiles to be seen. García-Alix’s personality is exceptionally pensive, his gaze sinking into the highway of the soul. And, above all, this focus applies to one of his most constant models, himself.

García-Alix has photographed himself as a young man in Italy in 1986, flanked by two voluptuous and Fellini-like prostitutes; naked and displaying his tatoos at the edge of a swimming pool in 1991; with disheveled hair and wearing a black dress in 2002. Over the last few years, these self-portraits, or “x-rays” as he calls them, have become more frequent, to the extent that they were the exclusive theme of an exhibition at the La Virreina palace in Barcelona during the first half of 2013.

In an interview for the Catalan newspaper La Vanguardia, he said “I have developed a lot because I have learnt to hear my interior voice, and as the years have passed I have become more precise and concise.” But the years have turned him more taciturn too, adds a frequent observer of his work: “It can’t be said that García-Alix has got older, but we can see that his desire to live has deepened and his gaze has become more melancholic,” wrote the Spanish critic Francisco Calvo Serraller. In an essay with the title “Shots in the Dark”, Serraller draws our attention to some of the “self-portraits” where all that can be seen are his shoes, or the pointed-toe black boots worn by motorcyclists. “The shoes we wear not only demonstrate one’s taste, but also show the way we move through life, a way of life and, finally, the way we are,” writes Serraller. The critic sees in these objects a clear sign of the street poet, the wanderer, the globe-trotter – a contemporary version of what Baudelaire called “the painter of modern life” 150 years ago.

But those who think that this “easy rider” is only an artist capable of improvising, of sketching, of the moment that presents itself, deceive themselves. Many of the portraits are carefully planned, with an eye for detail which is not at all random or accidental.

“It’s not easy posing for Alberto,” says Ana Curra, singer in the Spanish afterpunk group Parálisis Permanente and one of the many muses to this man who loves women. “He’s really meticulous in his composition and can drive you mad trying out different positions for your hands until he gets exactly the pose he wants.”

But we also need to hear Ray Loriga, writer, film director, and García-Alix’s friend (and occasional enemy): “Alberto is the result of an impossible combination of madness and strategy. On one hand, he is a restless hunter. On the other, a surgeon with diabolic precision, capable of ripping the heart out of someone without leaving a mark on their skin. He’s a master of both noise and silence.”

García-Alix himself wouldn’t disagree with any of this. “When I give lessons in photography, the first thing I attempt to teach the student is to get rid of everything that is extra. As for what is missing… Ah, that is a difficult topic,” he writes. “A photograph should always have an air of mystery about it. The mystery of life, of the next bend ahead.” ///

Alberto García-Alix (1956) was born in León, Spain. He moved with his family to Madrid in 1967 where, in the late 1970s, he began to photograph, recording the frentic times of the movida madrileña. He received the Spanish National Photography Prize in 1999.

Cassiano Elek Machado is a contributing reporter with Folha de S.Paulo and curates the debates for the International Photography Festival Paraty em Foco.

///

Get to know ZUM’s issues | See other highlights from ZUM #5 | Buy this issue