Metropolis

Publicado em: 7 de March de 2024

He is nobody´s, but therefore he is not a street dog either. Perhaps, more precisely, he’s a neighborhood dog, from that neighborhood, any neighborhood, which is what makes him unique, as well: if we’re to recognize him, we’ll need a few more very particular and precise details. And, even unitentionally, he can do it, like when we breathe, sleep, or walk. Sleeping and walking – those are what mainly defines his life. He sleeps with her, he walks round the neighborhood. Almost every day, she leaves the neighborhood; when she leaves, he starts prowling around. But there are also days when they go for a walk together.

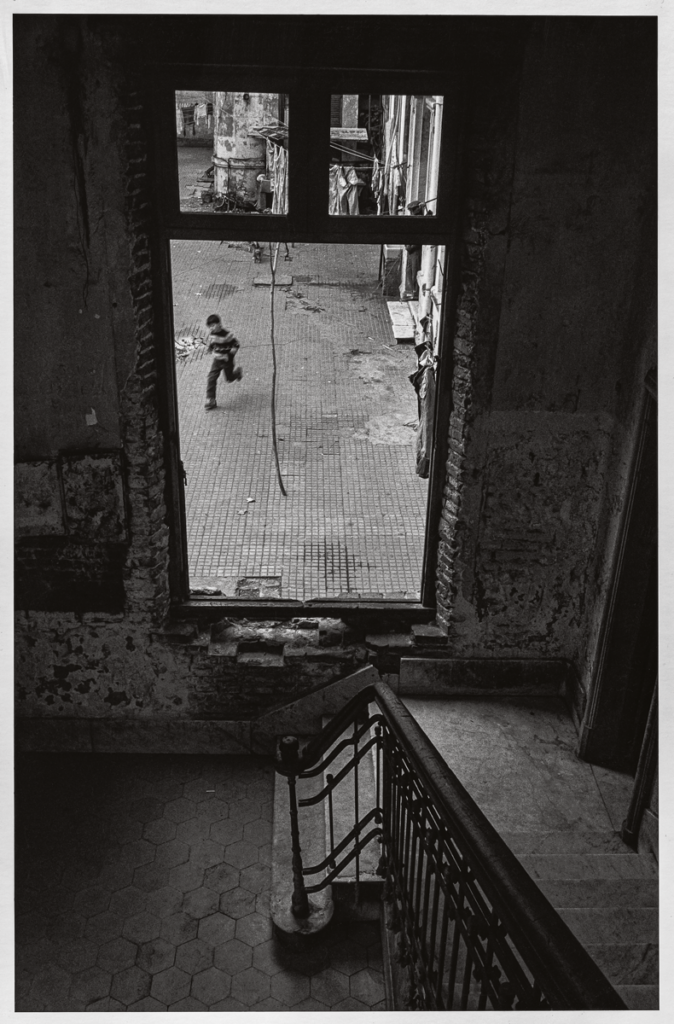

This morning they went down the crumbling steps together – her running, him moving at his own pace, which would slow down when passing the wooden gate of the big house. The gate is the threshold that separates their day ahead: she opened her umbrella and headed off to the left, in the direction of the avenue six blocks away, nervously taking care to avoid the loose paving stones and the water trapped beneath them, which may gush out, and there she waits for the striped bus to arrive; he pauses for a moment on the cracked marble doorstep, taking his time before deciding what to do as he watches her walk away.

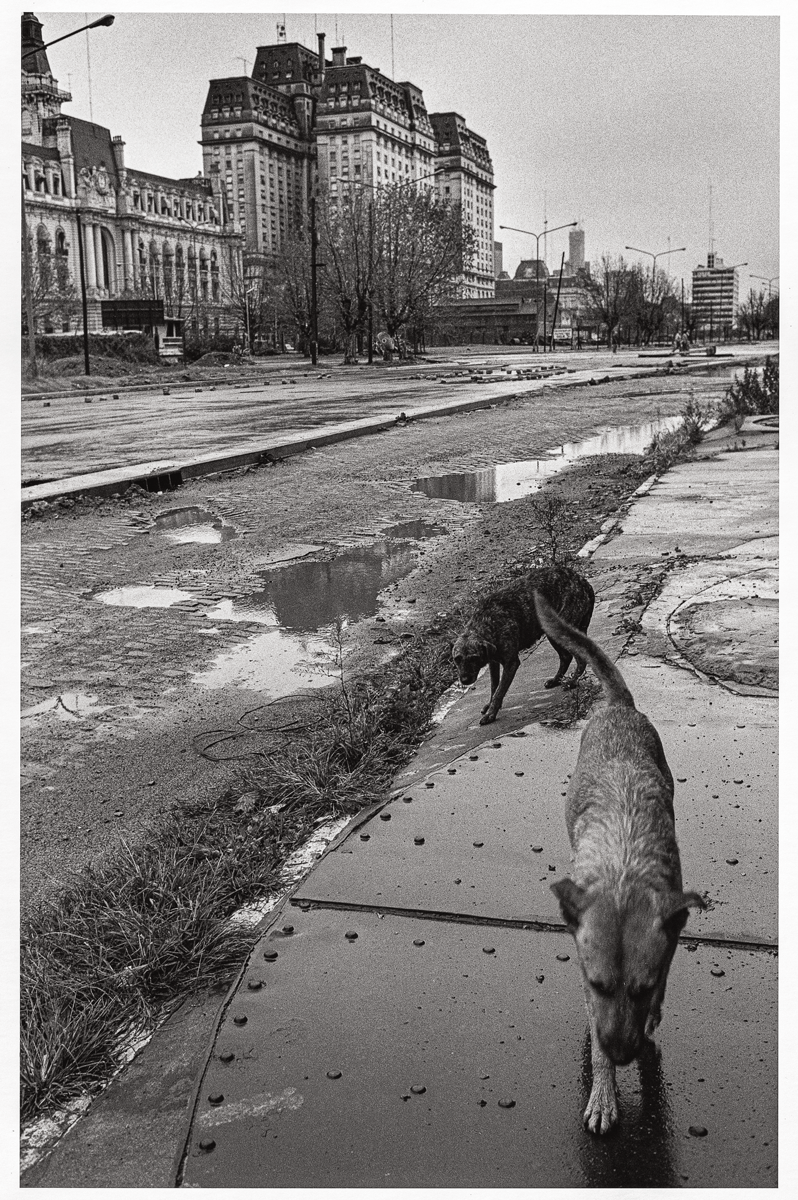

It never occurred to her to leave him locked up at home, as other people do in other neighborhoods. This is a rare thing there. The dogs are in the street, where there is also food and company, and not imprisoned behind a gate barking, as they wait for someone to come, or startled by passers- by. Yes, there are waits and surprises, of other types and quite variable, depending on where they head for each day. In rainy days, like this one, the main thing is to avoid getting soaked and shooed away. The wet fur makes the dog feel cold, and, which can be worse, it puts people off – her in particular. But that can happen later on – now he’s got the whole day ahead of him. His life is a series of snapshots, with him as part of the scenery, as in a set of photographs in which what the passing of time has erased gets hightlighted. He is capable of living just for the moment, in its almost still dimension, because he’s not used to looking ahead to the present. He stayed where he was for a while, keeping an eye on the tenement on the other side of the street, where there were some movements too, until he moved off in the opposite direction to her, heading for the park.

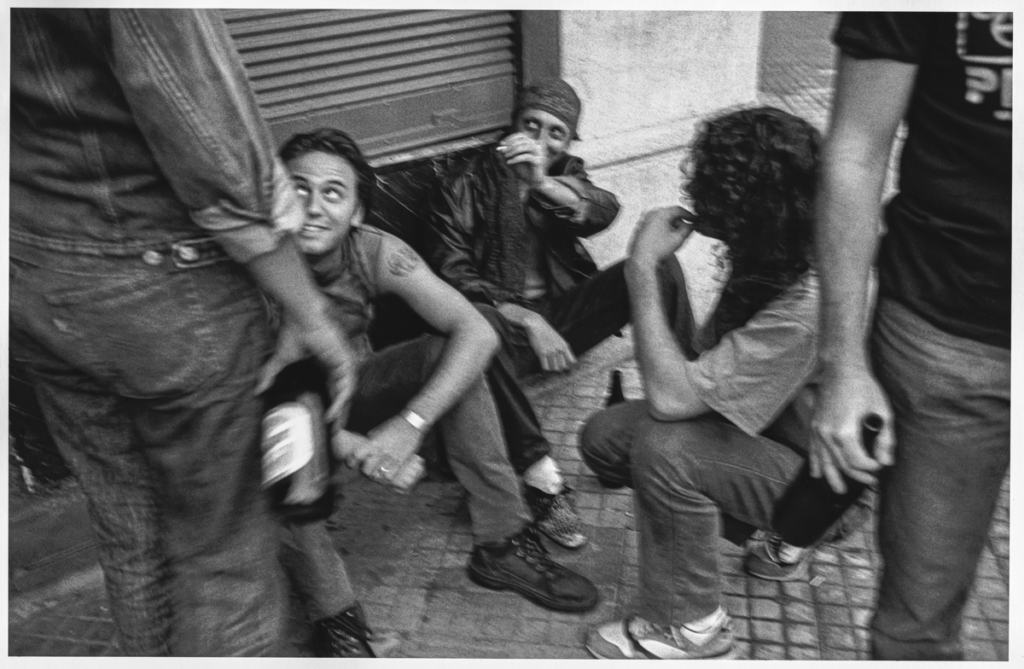

The park is his favorite place in the neighborhood, despite the challenges it offers. It’s occupied by strange dogs looking for scraps and boys willing to run after any animal. He likes the boys, though sometimes they cannot tame their impulses. There is never too much playing, except when it’s painful, because kids push, step on him, shove, or aim a kick at him, provoked by that energy kids are so full of, swaying between joy and violence. By watching their movements, he would see them hug each other and then shove each other about, in order to tell from the expression on their faces and tone of voice where their play would be heading, deciding whether to get involved or not.

He normally ignores the dogs, although it annoys him that they tend to put people off from getting close to them, as they don’t know how to wait. They have no time to lose. There isn’t one day after the other. They almost always want food. On days like this, they also want somewhere to shelter. They don’t know anything about set mealtimes, or that the weather changes. Or perhaps they do, but as they’re just passing through the area, they prefer to risk getting a kick to wasting time calculating things that their changeability makes pointless.

He moved on a quiet street. There are several like it in the neighborhood: if it wasn’t for the cars and the fact that they’re maintained and clean, despite being old, the streets might appear abandoned by humanity to a passerby in a hurry. That’s not the case with him, because he rarely hurries, perhaps never. Above all since they met and started to spend the night together. Now he knows he’s going to eat at the end of the day. And, until then, perhaps something will come up, usually in the park, which is the heart of the neighborhood. The neighborhood has a center and a boundary, marked by a small river, where they go together when they sleep late, cosy in the bedroom of the big house, and later they head out for a walk together, at a different pace from other days.

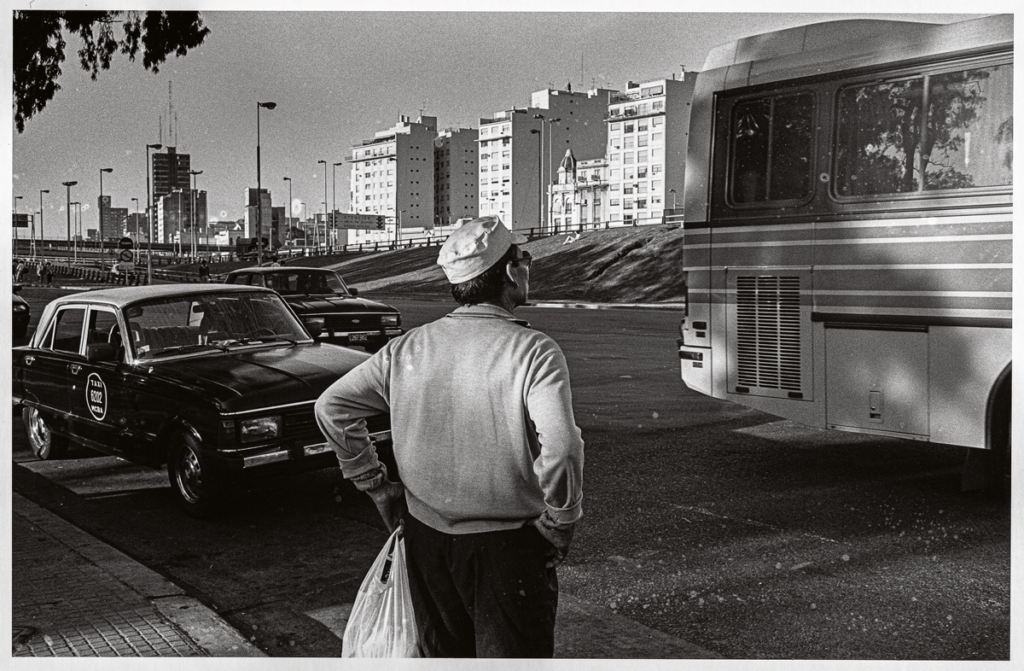

When he’s out on his own, he strolls around aimlessly, sniffing around, not looking for anything in particular, even though he’s waiting for something to happen, not really paying attention until it is time to cross the street, as it’s not unusual for animals to be run over in that neighborhood, so caution is needed at street crossings like this, where we get distracted and forget that this is where a striped bus passes by, imposing, noisy machine that sometimes goes unnoticed in the din, sometimes is the object of expectant gazes. Sometimes, like now, it reminds him that this is a metropolis.

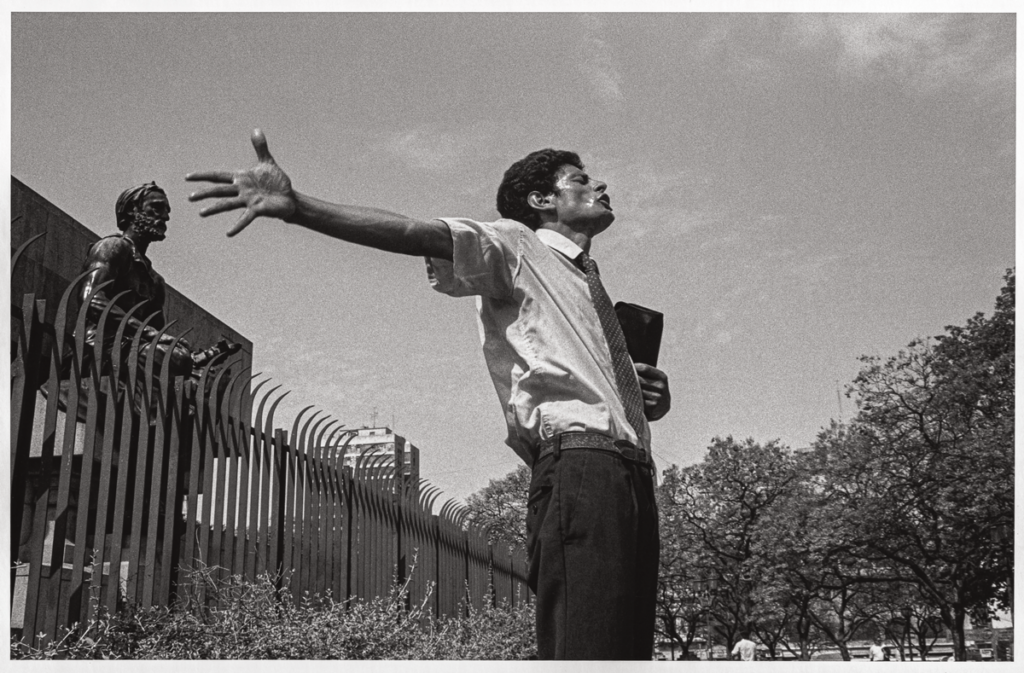

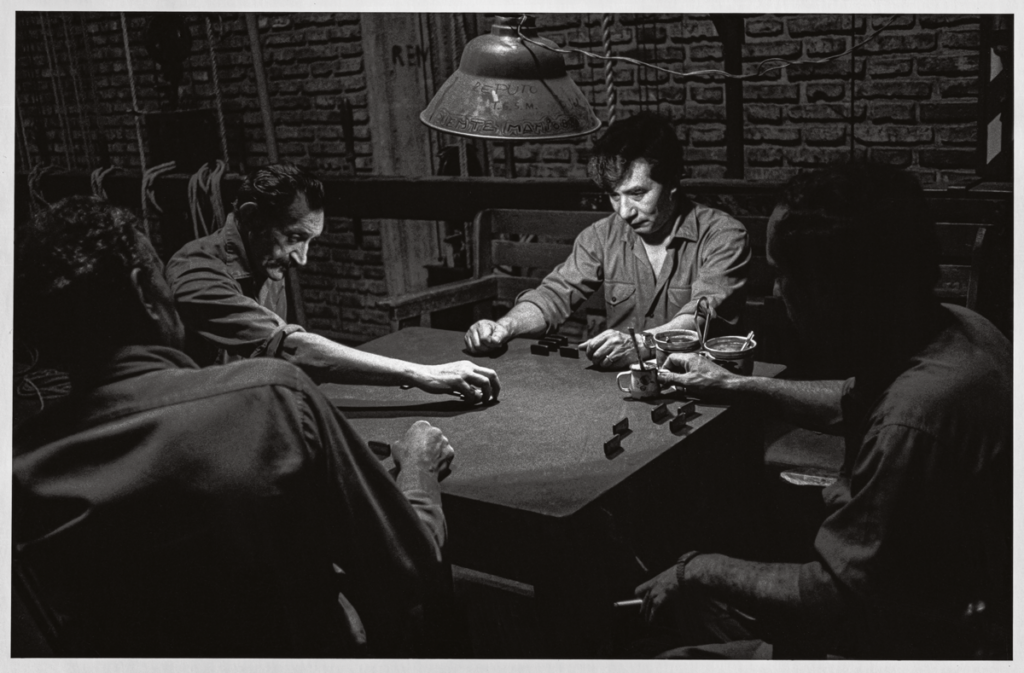

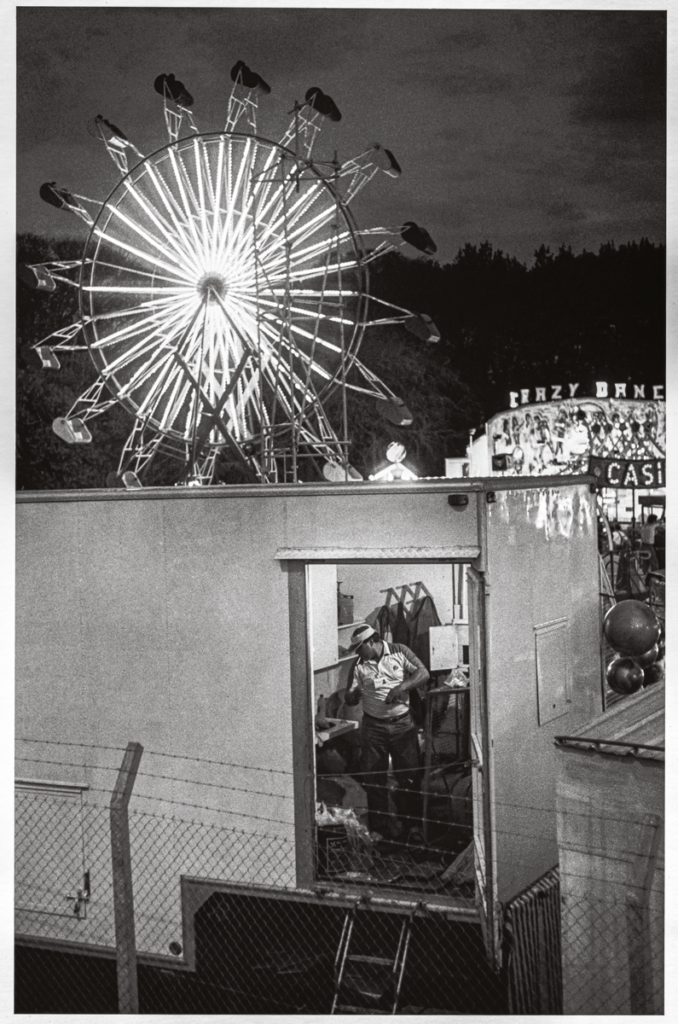

It is impossible to forget this in the park. Even early in the day, people are going about their business, even if that only means waiting. People wait standing or sitting, at the bus stop, in line, at a shop counter, clutching their bags, a little worried or a little suspicious, their thoughts at the tip of their tongues – an interjection, a request, a command, a compliment, a provocation: “What are you looking at?”

A young woman has just shoved a guy away. Clutching a bottle, he moves away to join other people, also holding bottles as they stagger away, arm in arm, laughing. She sees the dog and recognizes him. He’s the one which hangs around the big house. Every day she hops on that striped bus, but in the opposite direction, and before that she always stops by the kiosk in the square for a hot drink, especially on cold days like this. It’s good that it is warmer today, and he could accompany her to the counter where the two of them will wait, each of them eating in their own time: first, the food arrives for her, and then she slips a scrap to him. The scrap falls to the ground; he smells it, finds out what it is, savoring it. The young woman chats for a moment with the guy in the kiosk, pats his head and heads to the bus stop.

The kiosk is his favorite place in the park. He could spend the whole day there. There’s food available from early morning, and at midday there’s a feast of smells and scraps, many people willing to drop pieces of food on the ground or even to offer scraps straight to him with their hand, normally because they have already seen him at the neighborhood or just because they trust the face of a dog that sleeps at home. But, when people begin to come closer, the other dogs start to get a bit anxious around the kiosk, waiting for a meal, so he ends up deciding to head off in another direction.

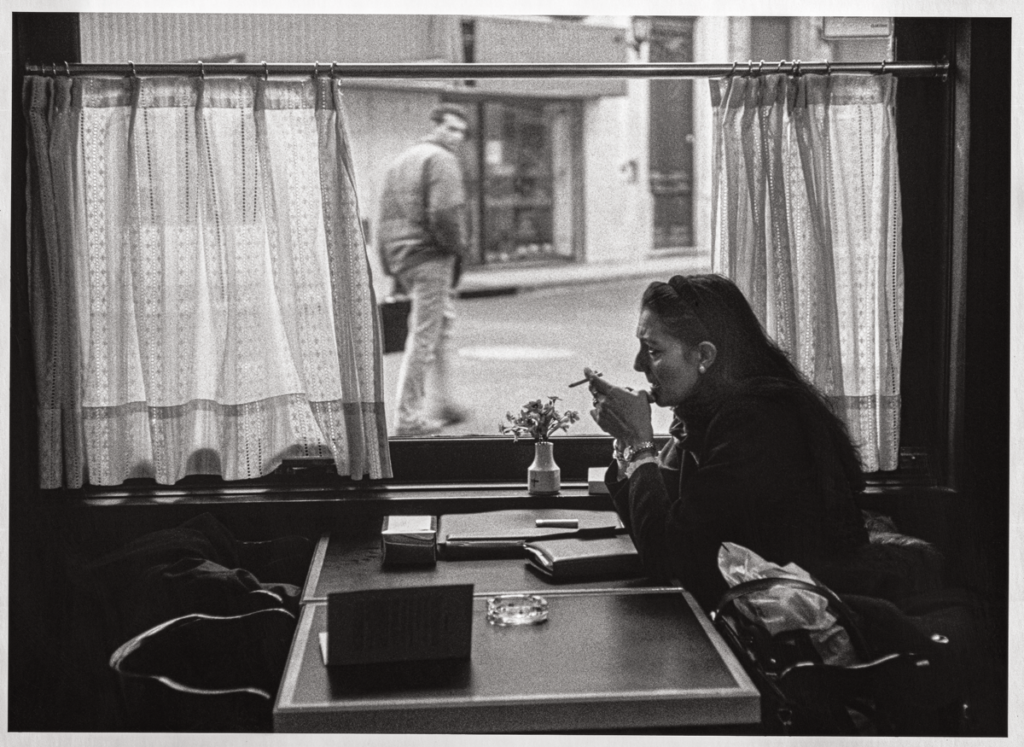

He goes to the street with the shopfronts. He sees how the people merge with the neighborhood: on a face watching him, a leafless tree and another big house, with its tall windows and iron balconies, which someone has turned into a clothesline now that warm sunlight has appeared from between the clouds, making the puddles on the asphalt shine. The reflections fascinate him, the transparent and bright surfaces that transform, amplify and intensify what is seen. At that moment, on the other side of the shop window scattered with rain drops, someone is watching him closely. The gaze looking at his eyes captures his attention. What does he want? He decides to get closer to the glass and then he recognizes a familiar smell – the lingering smell of smoke at the end of the afternoon, when she’s already returned home and before the night settles in, or when they have a long lie-in on the days she doesn’t leave the house. He’d like to be able to go in, but knows that it’s not allowed.

Except for the big house, closed places are hardly right for him, unless he’s with her, like that time when they went in the local club, where some nights couples slide around the floor keeping the same rhythm and paying close attention to the sound of the music. Even then, it didn’t work out that well, because he wanted to keep close to the couples, as if he wanted to play, which made her scold him, slamming and yelling at him until he was kicked out into the street. He kept waiting outside for her, thinking that she’d be angry when she left, but, on the contrary, she was excited when she came out and his being there made her even happier, as now she wouldn’t have to walk home on her own, late at night.

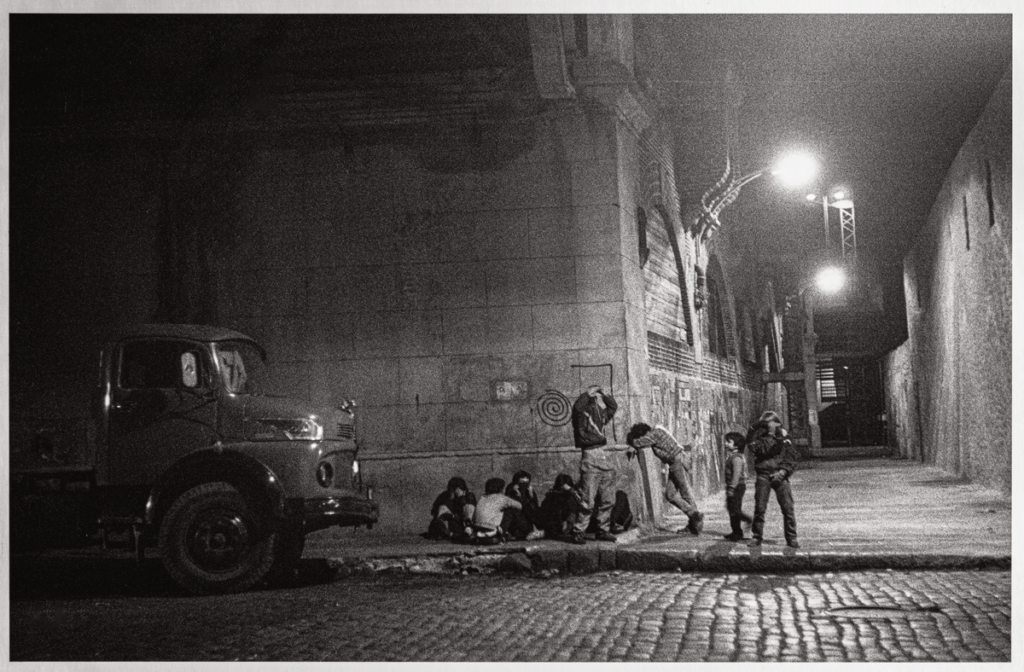

Walking alone is his call, but he isn’t bothered when he has company – another dog, or someone. Often, another dog follows him, thinking, rightly, that he knows his way around the neighborhood. Even now, a sandy-colored dog follows in his steps while sniffing his tracks on the road that leads to the bridge. He never goes that far, because the bridge makes him nervous, shaking and rattling on and off with every vehicle that passes over it. He prefers to go under its imposing steel structure, down there, on the banks of the stream.

That was where they first met, one summer afternoon. He’d gone down to the riverbank, attracted by a bunch of different-size kids having fun, they were pretty young and harmless, laughing and jumping into the muddy puddles. As soon as they saw him, they ran to him for some fun and, with their little hands, shoved him to go with them towards the women. They were standing around, chatting, in front of the quiet stream, surrounded by wreathes of smoke that quickly dispersed in the air. It was like being in another world, away from the metropolis, from its sounds and its frights.

And there she was, smiling as if posing for a photo, cradling a baby in her arms, which she then would hand to another woman. When they went up the road towards the neighborhood and separated to go back to their homes, she was the only one who paid him any attention, without a baby or child to carry or pull; so he decided to follow her, and she didn’t object. When they reached the big house, she spoke to the girl who was sweeping the steps, as if she had known the dog for ages: “Look who’s come along.”

This is the same route he is redoing now. He’s not that wet, nor is he very tired. It’s been a quiet day. Soon he’ll be able to lie down next to her on the mattress, after she’s changed, taking off the damp clothes of the day and hanging them on the hanger; or, who knows, if the rain doesn’t start again, he’ll go with her when she goes for a chat on the big house’s veranda, where he can entertain everyone by running after a chicken; or perhaps they’ll go for a stroll together around the block, quiet at this time of night, to look at the moon as it appears between the clouds. ///

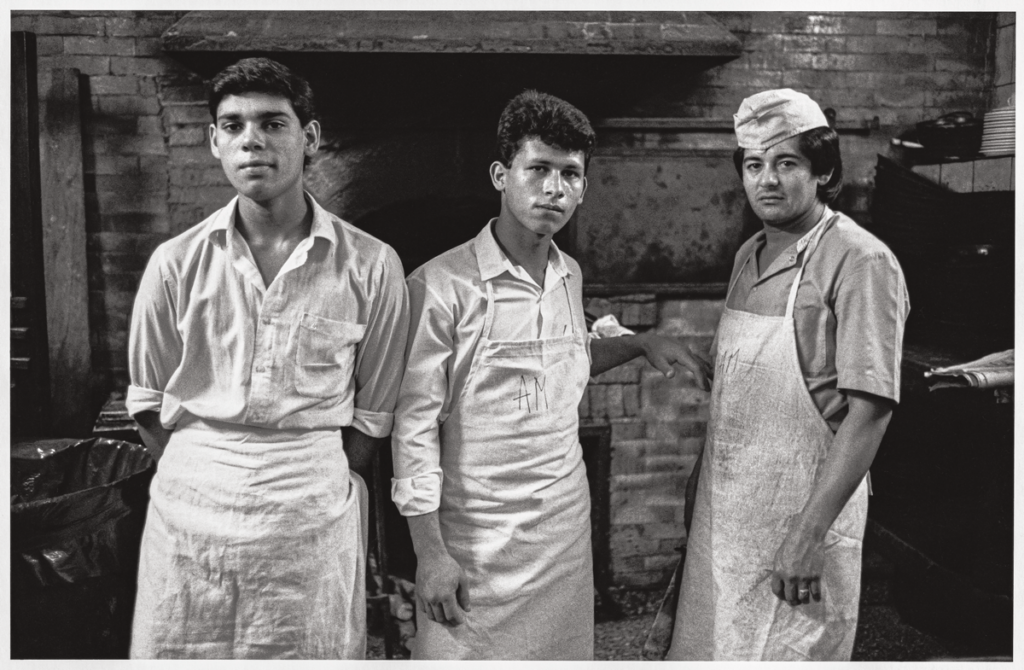

+ Metropolis: Buenos Aires 1988/1999, by Adriana Lestido (Lariviére, RM, 2022)

Adriana Lestido (Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1955) is a photographer. She has worked as a photojournalist for the newspapers La Voz and Página/12 and for the agency Diarios y Noticias (DyN). She has published seven photographic books, including Mujeres presas [imprisoned women] (Dilan, 2001), Madres e hijas [mothers and daughters] (La Azotea, 2003), Lo que se ve [what one sees] (2012) and Antártida negra [black Antarctica] (Tusquets, 2017).

Paloma Vidal (Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1975) is a writer, translator and professor at the Federal University of São Paulo (Unifesp). She has published, among others, La banda oriental [the Eastern side] (Tenemos las Máquinas, 2021), Pré-história [pre-history] (7Letras, 2020), and Wyoming and Menini (7Letras, 2018).