The great time

Publicado em: 4 de December de 2023

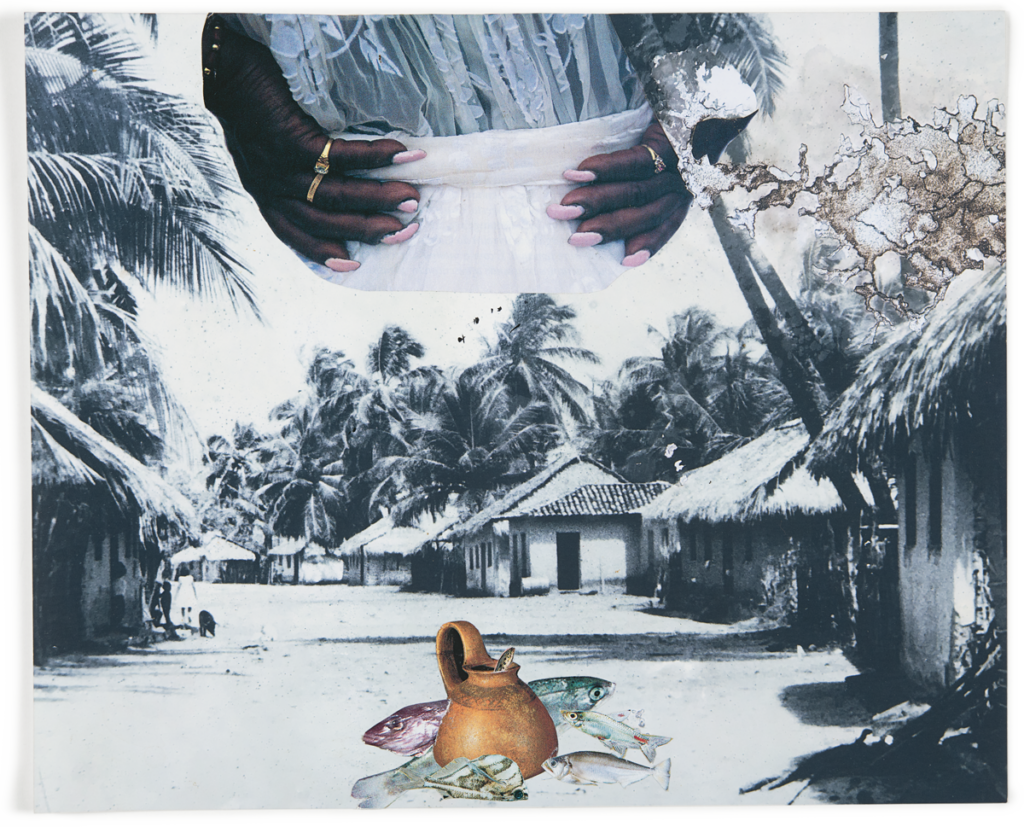

Details of the jewels on the fingers, nails are spear tips. Closed fists clasp on the waist asking for equality. Let the high point be a dimension of energy favorable to us to break down and bring down greedy rockets. They do not go up, they turn into iron embers. At the great time they kneel before the candles and continue; the force of the forest enters the communication. – Gê Viana

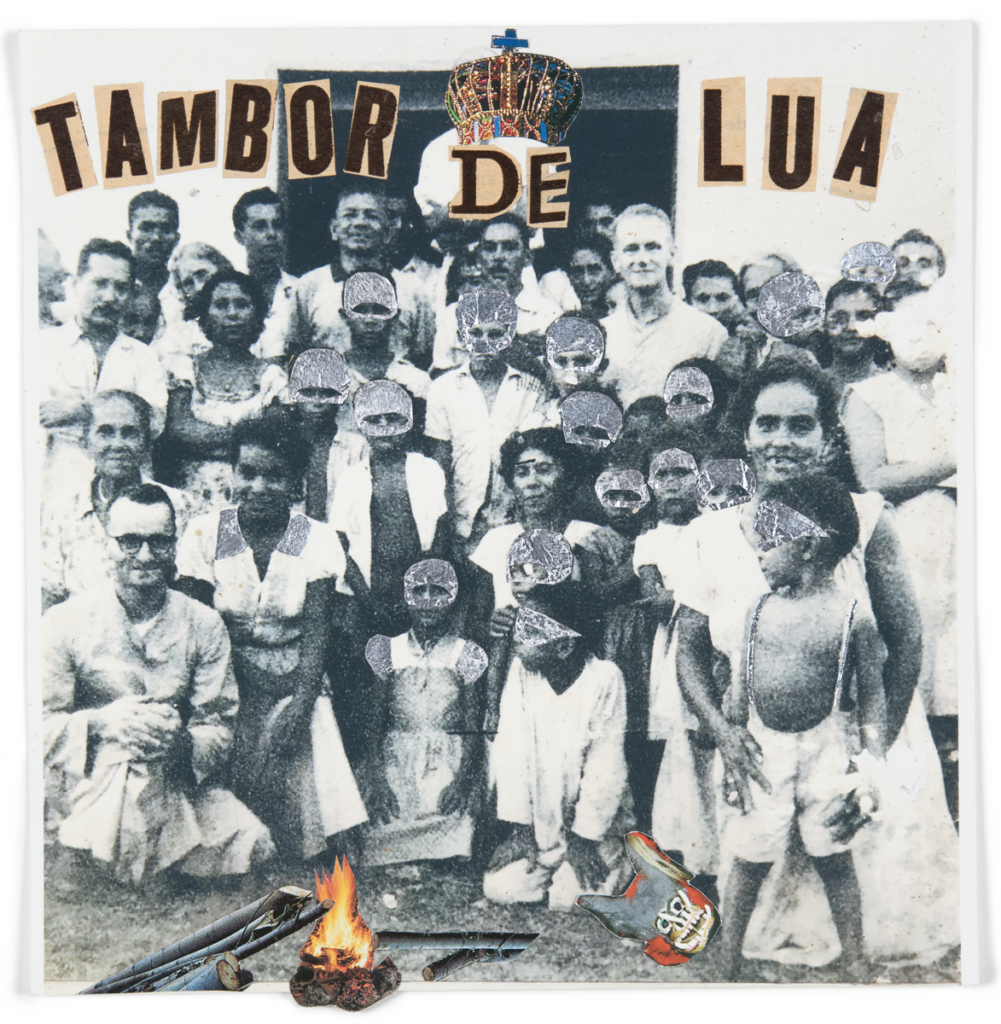

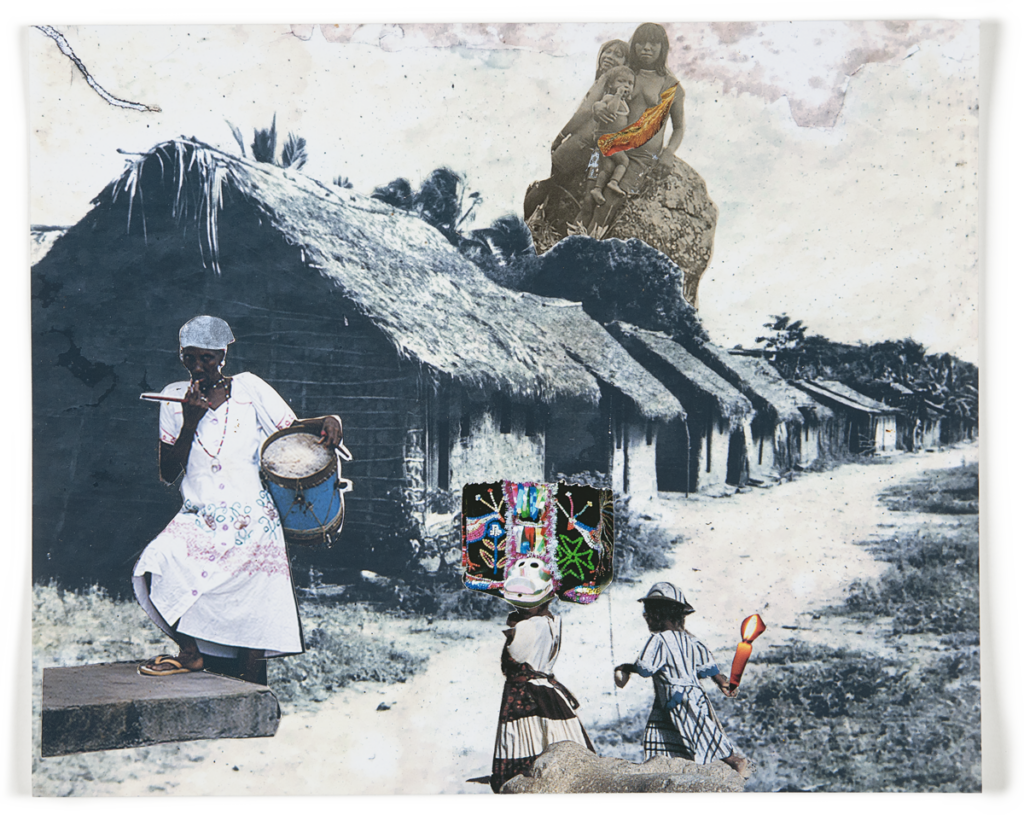

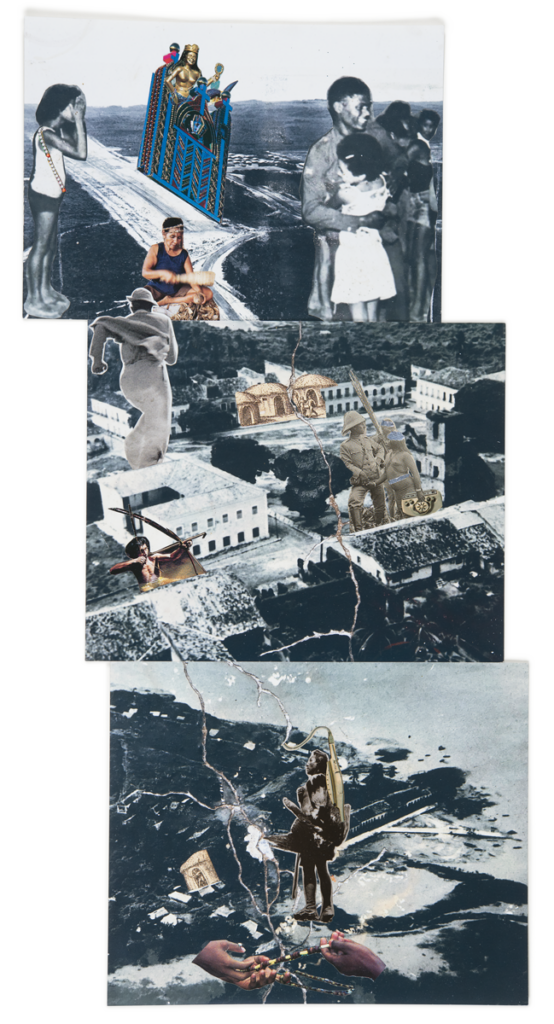

To look at an image is to walk around an island. But Hora Grande [The great time] (2020) describes a peninsula: Tapuitapera, the original name of Alcântara, in collages carved by Gê Viana’s machete, based on photographs taken between 1939 and 1986 along the route between the river mouth, the islands and the continental part of the territory.

The accumulation of different times and textures in the artist’s work is an extension to the experience of life in the quilombo [hidden and fortified place where slaves escaped from captivity were sheltered]. The sea foam of Cumã, the series of collages shows, in a dive, the good way of life in this village.

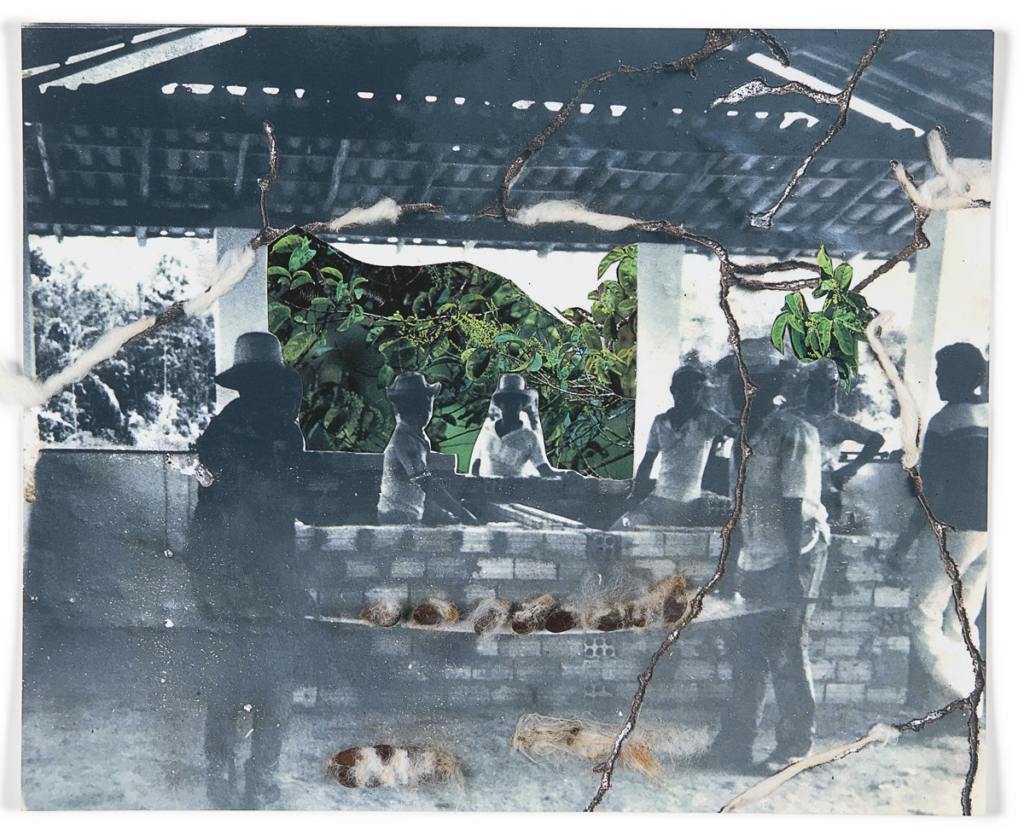

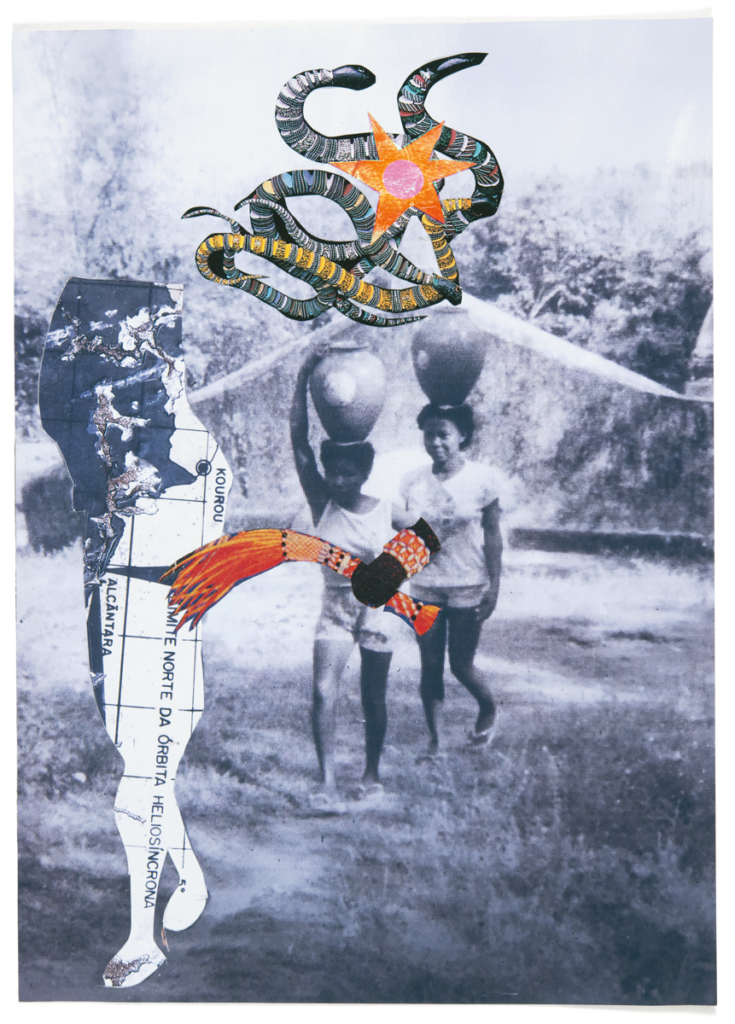

In Maranhão, we call “branches” the paths, the secondary roads, usually made from dirt or crushed stone, which interlink the communities from within. The collages work to show us this quilombo by means of a new document. Distressing the archival images with saltpeter, Viana transforms photographs from the collection of museologist Julio Abe, obtained from panels of the exhibition Museu de Rua de Alcântara, [Alcântara’s Street Museum], 1986, eaten away by termites, into branches connecting different times. Hora Grande is an imagination of the quilombos, a territory that has historically resisted destruction.

The installation of the Alcântara Space Center (CLA) in the 1980s generated a process of brutal violence in the lands of the black population. In a criminal process, the lands and sacred places of the quilombolas were expropriated and their direct access to the coast denied – in short, the possibilities of life arranged according to the typical intelligence of the quilombos were removed. The ongoing genocide and ecocide, with the possibility of expanding the area of the CLA, stem from an extensive predation movement. Turning back in time to see further – a possibility triggered by the collage – the advance of the CLA on the territory can be understood as part of an ancient history of killings.

In the map of the “Todo Maritimo da Terra de Santa Cruz” [all the maritime area of the Santa Cruz land], from 1640, the location of some Tapuia villages are identified. Tapuitapera, one of the largest Tupinambá villages, according to the records of the time of contact with the French, is delimited in the peninsular area of Alcântara, on the border with the “White Settlement” which connects the peninsula to the continent. At this point, the colonial city advances and retreats in the historical conflict with the original and black populations that entrenched themselves.

The premeditated expansion of this colonial city threatens the biomes and alternative lifestyles with the ever-expanding practices of sugar and cotton monoculture and the maintenance of the slaveholder regime – which remains in place to this day. Between the settlements of the whites and the Tapuitapera, there is a radical conflict of thought and worldviews.

Anacleta Pires da Silva, the leader of the quilombo Santa Rosa dos Pretos, in Itapecuru-Mirim, says that, in order to resist in the quilombos, it is necessary to understand the territory as a body, not as separate allotments, separating the head from the limbs. What happens today in Alcântara is a genocide, part of a policy of extermination of quilombola territories cut by the BR-135 highway, by soybean plantations, by the railroad – the destruction of life, consumed by capital.

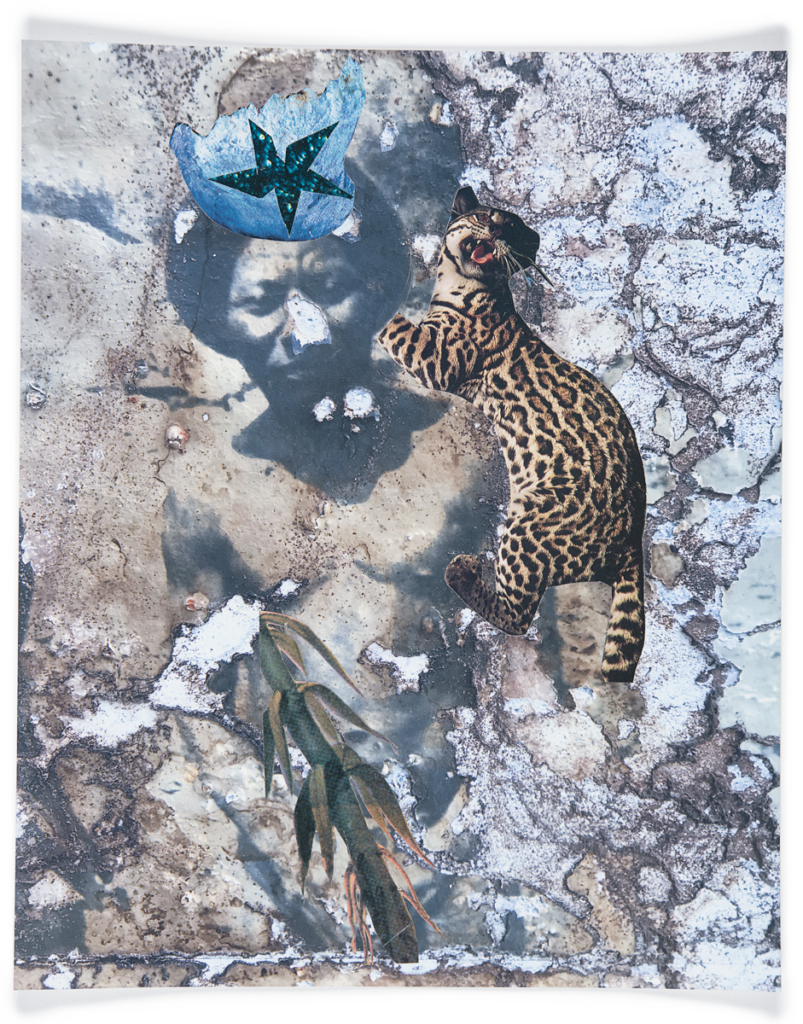

Imagining another future, using memory as a weapon of war, Viana’s collages provoke a distortion of scene, a mirroring. Her noisy observations mix the colonial structure, worn out by time, scoured by the sea mist, and the advance of nature; in these images, history seems to encompass the polyphony of a party. The clipping of Tapuitapera photographs opens tracks all around the forest, which resurges with a historical force and vital resistance. When the forest advances, we understand that nature takes care of itself. The narrative of this biome, with its whistles, buzzes, the various subjects and sounds, tells that, above the ruins of the village of the whites, Tapuitapera lives.

The green washes over both black and white; the taperas [ruined dwellings] surrounding the central courtyard of a village; the golden emerald of jewels, the palace of Ina, Princess of the Waters, at the bottom of the sea; the hands on the waist calling the punga, the circle of Creole drums, in which everyone plays. In the dream, the vision of the campfire, celebration of St. Benedict, the search for the Mast of the Divine in the mangrove forest, the shine of pindoba [a kind of palm tree] straw mats and the Crown of the Empire. Children of fish, of birds, it is as if we have heard the river Tapuitapera, the wind, the birds as part of this whole.

The dam from Viana’s work irrigates – brings to life – different resistance policies agreed by the communities, in their rituals, their festivals and internal organizations, which draw an alternative intelligence to the colonial models. We can make up the collages as the brackish and cloudy water of the Tapuitapera mangroves, through which one cannot really see the bottom. These images hold a precious quality of mystery.

While our flattered eyes fill with tears at the image of the Pelourinho, the CLA rockets and the colonial town houses, wishing for the collapse of these structures, Viana macerates the photographic archive devoured by termites, calling the land at the great time, asking for protection for the mother from whom we came. ///

Images: courtesy of the artist and Galeria Superfície.

Dinho Araújo (Pinheiro, Maranhão, 1985) is a visual artist and holds a master’s degree in anthropology from the Federal University of Paraíba (UFPB). He was curator of the exhibition Caminho de Muriá para brocar a terra

[Muriá’s path to drill the earth] (2021), by Gê Viana, at the Historical and Artistic Museum of Maranhão (MHAM).Gê Viana (Santa Luzia do Tide, Maranhão, 1986) is a photographer, performer and researcher. She presented the exhibitions Retirar o sol das cabeças, uma reza das imagens [removing the sun from heads, a prayer of images] (2022), at Galeria Superfície, in São Paulo, SP, and Paridade [parity], at Sesc in São Luís, Maranhão (2017). She was a resident of the Pampulha Fellowship in 2018-2019.

CAPTIONS AND CREDITS OF PHOTOGRAPHS USED IN THE COLLAGES: p. 27: Workers opening up a road / Collection of the Parish of Saint Matthias. p. 28: Mirititiua Fountain. p. 29: Workers opening up a road / Collection of the Parish of Saint Matthias. p. 30: Canadian priests visiting Iguaíba, Our Lady of Fátima Chapel (1956). p. 31: Farm workers’ manifesto (1986) / O Imparcial newspaper archive. p. 32: Assembly of the Mecb [Complete Brazilian Space Mission] satellite model / Archive of the Institute of Space Research – INPE. p. 33, above: Path to the Mirititiua Fountain (1939), by R. Lopes / Sphan Archive; below: Village waits in its new facilities (1986), by José Anselmo da Silva. p. 34: Mirititiua Street [Mirititiua] / Collection of the Parish of Saint Matthias. p. 35: Village of Ponta da Areia / Collection of the Parish of Saint Matthias. p. 36, above: Aerial view of the airport and NUCLA (Implantation Core of the Alcântara Rocket Launch Center) / Andrade Gutierrez; center: Aerial view of Praça da Matriz (1985) / Andrade Gutierrez; below: Aerial view of the Porto do Jacaré (1974) / Sphan Archive – Pro-Memory. p. 37: Itamatatiua – Saint Tereza Festivities (1957) / Collection of the Parish of Saint Matthias.