Memory needs to move ahead

Publicado em: 29 de June de 2023

Born in the indigenous territory of Porto Lindo in 1975 in the municipality of Japorã, in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul, Sandra Ara Benites has a long history in education. She was a teacher, and worked in the administration of public education in Mato Grosso do Sul, Santa Catarina and Rio de Janeiro, reflecting, researching, and writing essays on the challenges facing indigenous education.

We worked together on the exhibition Dja Guata Porã – Rio de Janeiro indígena [Dja Guata Porã – Indigenous Rio de Janeiro], organized by José Ribamar Bessa and Pablo Lafuente at the Museu de Arte do Rio in 2017 and 2018. Since then, we have shared an interest in bringing together, bewildering and developing the relationship between curatorial and educational practices. In the first half of 2022, we began putting together the group Retomadas [re-takes] for the exhibition Histórias Brasileiras [Brazilian stories] in MASP (Museu de Arte de São Paulo), which was under the overall direction of Adriano Pedrosa and Lilia M. Schwarcz and the collaboration of many other curators.

In May, we decided to cancel the project, after MASP vetoed the inclusion of six photographs by Edgar Kanaykõ Xakriabá, André Vilaron and João Zinclar who document the struggle of the Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra [landless rural workers movement] (MST) and indigenous movements against the colonial looting and unequal distribution of agricultural land in Brazil.

What happened from then on – a public debate and a struggle until the group was reinstated in the exhibition, this time including the photographs – is here the guiding thread for a reflection on what the images may teach – and what perhaps they cannot teach.

Sandra, is there a term in Guarani for “image”?

There is. It’s ta’anga, a word that means “something captured” and, because of that, has become an image that is not true, that is not the thing itself. A photograph or a drawn figure can be ta’anga.

We also have nera’anga, which means a thing that is no longer, as if it were a shadow or a replica – images of you that are not you in reality. Nera’anga can be a reflection, a photograph or a drawing produced without the presence of the person depicted. Therefore, it indicates something that no longer is related to what is represented.

Ta’anga and nera’anga convey this idea of an image that is emptied of truth. We think that producing an image may empty someone.

One of the Guarani’s perception, which is revealed in the meaning of these words, is that someone may want to be you and, in order to do that, steals your image. Nowadays, on the other hand, having an image captured is important because the memory of photography serves as proof, as a complaint. We, the Guarani, use photography as a weapon in our struggle. On the other hand, the image can be dangerous in other situations, because photographing can be a way to take the place of the person represented.

These two terms, ta’anga and nera’anga, come from a’anga, which in turn comes from angue, which means “soul that no longer exists”. For us, angue is as if it were your trail. It’s no longer you. It may be something you left or something that comes from the place where you lived. But it is only a trace of your presence, not your spirit. For the Guarani, the spirit and the soul are not the same thing. The spirit, inhe’˜e gue, is true, it is a being that can exist even without a body, without producing traces of its presence. Angue is not the spirit, but its emptied image. It is a kind of “soul”, the trace of a presence that no longer exists – a presence that may even be invisible. Angue is a kind of ghost, shadow, the trace of someone. Images are a kind of ghosts.

Then how do we deal with the images from the Guarani’s perspective?

Recently, in the village of Pico do Jaraguá, in Sao Paulo, I was having a conversation with relatives who are thinking about the types of presence and representation of the Gua- rani in the Museum of Indigenous Cultures, where I work.

At one point, a young man mentioned that he was thinking of putting some photographs of a xe ramõe (“elderly man”) and of an elderly lady who had died on display in the museum, as a form of tribute. But the older women in the group, who were taking part of the conversation, were against it. They did not want the images of xe ramõe or xe xajaryi (“elderly/old woman”), already deceased, to be displayed in the museum because, for the Guarani, the image that should remain is not the photograph, but the essence of what the person did in life.

When we want to remember someone who has gone, we talk about the person’s spirit. We speak about their way of being, about what they did. We discuss why they were good, and what they did to be remem- bered. We speak of the person: not of an im- age that was done and is a souvenir, because, for the Guarani, a photograph is a memory without spirit. And for us, what is important is the spirit of memory.

This spirit of memory is sacred because it brings, at the same time, the pains of the struggle and challenges that these people lived on Earth, but also the teachings that they brought to the community. Despite bringing sadness, memory is sacred, be- cause it is learning. And what it teaches is not the photograph as such, but the collec- tive memory of the lives represented by the images, who the people and their journeys were.

To be ancestral, the person has to be constantly remembered, brought back to presence, summoned in stories, in conversations, in rites. Ancestry is a condition that is produced every day. The ancestral is continually being created, like what happens to the “classics” of the juruá (“non-indigenous”) world in an uninterrupted process of canonization through education, media, science, and symbols.

When you talk about the elderly lady’s concern, I get the feeling that she was attentive to the risk of the image – and, in particular, photography – acting against the process of ancestry. For when one believes that someone’s spirit has been captured in an image, one becomes bound to a past memory of this spirit, preventing it from living vividly in the present on which it depends to become an ancestor.

This has to do with the way we, the Guarani, understand time, which for us is the ara pyau (“new time”) and the ara ymã (“old time”). We have no present time. The “pres- ent” is the moment, not a chronological interval. What we have is the moment of now and times that come and go.

We can say that ara ymã has to do with the past time, and ara pyau with the new time, the future. For the Guarani, the old and the new do not form a linear sequence. These times occur in cycles, as with the periods of the year, which are continually starting over again. In these cycles, at various moments, ara ymã and ara pyau approach and meet. The two times flow, move. The past and the future are not fixed places in time.

They are not even still in space…

Exactly. That is why we say that we are moving toward the future, which we call tenondé. What is tenondé? It is “in front of you”. That’s when you go walking, go forward. This “forward”, which is only yours, is the tenondé. The future moves along with you.

It’s not a place, is it? It’s a position.

Yes, because the future is the body walking, moving ahead of you. To walk is not to predict the path ahead, but to prepare the body for the journey. This is important because, in your journey, if you find something that is not good, you can prepare to leave this place, to take other paths and not harm yourself. The future is a process.

The past also moves with the body. So, if you have a memory that is important and must not be forgotten, you need to carry it forward. You can’t just capture the memory. You need to keep it close to you, move it ahead with your body. The past is also a journey. That is why memories – both new and old – need to walk.

The movement of walking wakes up memory. We need to wake up our memories. But what is very important to understand is that waking them up is to be in agreement with them, since their place is the body itself.

This happened with the photographs of the landless rural workers movement in Histórias brasileiras, at MASP: we woke up the MST memory, but we had to be in agreement with it. We had to honor the fighting spirit represented in the photographs so as not to empty them politically. It was this commitment that led us to cancel the Retomadas group when the museum prohibited the presence of the images.

To keep that fight awake at MASP, we had to be in agreement with the confrontation that it demanded of us now. Only in this way can we walk with these memories, building a future in which they can keep their fighting spirit alive.

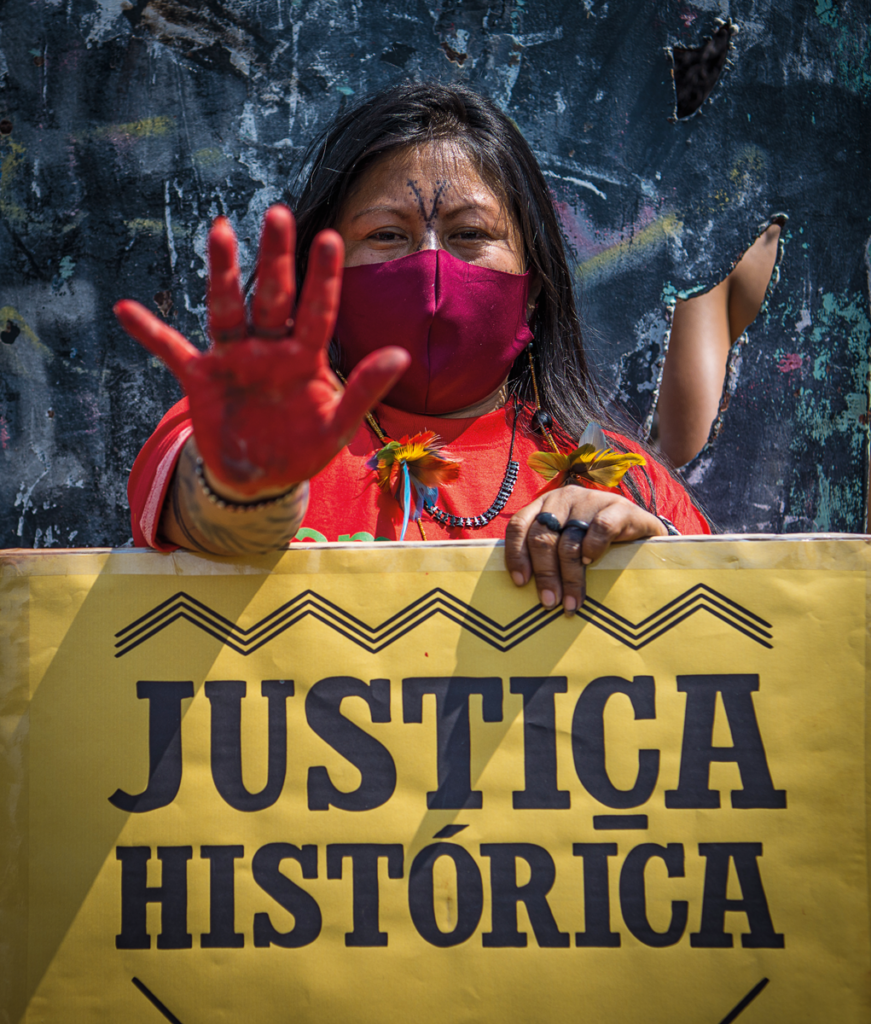

You mentioned the two central aspects of our conversations around the photographs of André Vilaron, João Zinclar and Edgar Kanaykõ Xakriabá in the Retomadas group: the fight and the journey. We arrived at these six photographs from the idea of a march, researching the iconography of marches, such as those historical MST ones. When the images were vetoed, we refused to stop them. We do not accept that they could not be part of the march, that they could not move ahead, go public, be in the museum and seed the world from there too. When we confronted the veto, the images continued their journey.

As my relatives said, when you take a photograph, it is as if you have also captured the spirit of the photographed person. But the spirit is not that frozen image, it is precisely the movement. That is why it is important to move the images, so as not to disrespect the spirits of the people or the struggles they represent.

When we resisted the veto, the images moved much more. In addition to being in the exhibition and catalog, they moved into the newspapers, became posters, spread rapidly through social media. And so they got us to move, didn’t they? We move with them. It seems that there is an ethical and political reciprocity in the relationship with images. To wake them up, we need to be in agree- ment with them, as you say so beautifully. To move them, we need to move ourselves.

That’s it. Especially these photographs, which are images of struggle. They are provocative – they cause movement.

The question is not if they are good or bad photographs, as the museum claimed and some others, too, trying to legitimize the veto, arguing that the MST and Kanaykõ images would not be “art”.

And, in response to the assumption that only a few images can be “good art”, we question in return: “This image is good for what? Good for whom?” It’s not a question of aesthetic relativism. It is about political use. If we want to dismantle the servitude that constitutes colonialism, we need to question for what and to whom the images serve. Their servility cannot be disguised by aesthetic approaches. Not even aesthetics should make them servile. It is important to face head-on the discomfort of thinking critically about our artistic practices. In the end, who do the images we produce and legitimize serve?

Because an image can be used for good and evil. What, then, would be the power of these images?

This is very important to me because these photographs represent a lot of struggle. They are documents and instruments of struggle. When I started looking at the photographs of the marches, the demonstrations, I soon came to the memories of the leaders who were assassinated in the process of confrontation and resistance. That touched me. We needed to show this, because the lives of these people are not yet taken into account in Brazil. I experience this pain every day. And who does that knows.

It is difficult for us to find spaces to show the perspectives of the social struggles, because what we want to show is frequently not received well, although we are showing reality. The images have an impact, and people retreat from the impact.

The images we have shown at MASP are not as shocking as, for example, the photographs in the Figueiredo Report, a set of horrendous images which document the crimes committed against indigenous people during the military regime. The photos in the report are extremely shocking because they reveal how inhumanly we were treated. Because they are so traumatic, they cannot be shown anywhere, so they are not even discussed.

These shocking photographs do not circulate. Only a few researchers or those who are interested in them know these images. That is why it is so important to show images of our struggles. And, in the face of denial, we need to prepare the territory to show them. That is what we did with Retomadas: we prepared the ground with newspapers, posters, speeches, works, showing not only the context of the struggles, but also the ways in which the images circulate.

We, indigenous people and people in the social movements, always need to prepare the public, because many people do not want to receive images that speak of concerns and break the silence. The media keeps erasing our images, realities and voices, cutting out small parts of our struggle, leaving visible only what the interests of the powerful accept to be shown. It is essential to be able to display our images in art exhibitions.

Xadalu Tupã, for example, with his silk screen images of indigenous carrancas [figureheads on river craft] exhibited at the Museum of Indigenous Cultures, talks about digging up heads. He talks about the city that is above us, as if all the villages were buried under the city. These images, when they are reproduced and thought about in another way, cause impact. That makes me very emotional.

Seeing the photographs of Vilaron, Zinclar and Kanaykõ, I feel as if I’m inside those marches. And then we ask ourselves: who benefits from these memories not being seen, talked about, revived? And how to take back images that have been captured?

When you say you feel as if you were inside the marches, you are attesting that the images of struggle are collective bodies. The political and aesthetic strength of these im- ages comes from their collective power, not from being unique pieces, captured, frozen and displayed as precious objects in an elitist museum.

We talked a lot about this when MASP proposed to acquire the photos it had vetoed. To the photographers and ourselves, the idea came in a biased way. The silence of the veto was not enough – the intent to purchase them seemed like a form of patrimonial erasure, didn’t it? Of using collectionism not to give energy to, but to stop the march of the fighting images.

Our counterproposal to MASP was to commission a large print run of posters of the vetoed images so that they could be distributed during the exhibition Histórias brasileiras, which did, in fact, occur. It was an attempt to walk in the opposite direction to the museal capture that marks Brazilian patrimonialism in its colonial and cunning implication between the public and the private, the State and the capital. We prioritize disseminating, moving and collectivizing the social and political imaginary of agrarian reform and the struggles of indigenous peoples, rather than making an exception of it in the form of collectible works of art.

We are still dealing with an aesthetic and politically relevant question: how do we continue with the body and the collective march of the images, from the perspective of curatorship?

This is a challenge for all of us. We need to think, reflect, listen. This is not something that is ready. It is something we can understand technically, but the challenge, which is always on the move, is open.

It is a responsibility for both the curators and the museum, for the artists, researchers and educators, for the public, etc. We need to be attentive to how to deal with it: how to receive, protect and reverberate this collective body. Because, while we are individuals, at the same time we represent collectivities. Silencing one of us becomes a silencing of all. That is what happened with the veto of the photographs in Retomadas. It was through the collectivity (in this case, everyone involved in the group) that we reacted to the violence suffered by some.

We must not forget that if we lose the collective, we will be more vulnerable. I’m sure of this, so I can’t accept situations that harm the collective. The collective body says more. It activates us more, moves us more. It is what underpins this attitude of affirming “yes” or “no”, which will say what the importance is and what the meaning of continuing the fight is. And it is what will echo our voice.

You’ve always said that you don’t want to be recognized by just your image, but by your voice. Perhaps it is important to talk about the voices of the images, the spirits that are in the images – those that sometimes we do not know how to hear and that, therefore, we silence.

I remember you talking about hendu, which is “listening with the body”; about how listening is an activity of the whole body, just as seeing is. In the visual arts, in general, we emphasize seeing, the visual dimension of the image. Despite all the sensory experimentations, it does not seem exaggerated to say that contemporary art is eyecentric. I have the feeling that we build a field that does not teach us to listen to the images, which does not provoke us to, say, “practice hendu”. The protagonism of visuality deafens.

When you say “I felt as if I was in that march”, you bring your body to the relationship with the photographs. It is not a question of witnessing the marches only with the eyes, treating them as documents. It is about inhabiting the image as a territory, involving your body.

I think hendu goes through the emptying produced by the image, reviving and releasing the spirits that were captured in it by listening. Couldn’t we think about something similar in relation to museums? How can we invite cultural institutions to listen with the body? How to activate hendu in our curatorial practices?

I think the experience in the exhibition Dja Guata Porã – Rio de Janeiro indígena showed us how voices, and not only images, can be the backbone of curatorial practice, something that you and I experienced and that we talked about, didn’t we? We are still trying to understand.

I remember that in 2016, while we were preparing the exhibition, we held meetings in various villages, listening to people’s wishes and interests. The last one we visited, the village Iriri Kanã Pataxi Üy Tanara of the Pataxó Hãhãhãe people in the municipality of Paraty, Rio de Janeiro, brought us a sense of the urgency to establish the border of their territory, at the time recently recovered.

The next day, one of the curators, Professor José Ribamar Bessa, went to speak to a public attorney to help us seek what the relatives wanted. We all took action and widened the struggle to draw the boundaries of the village from what we heard when we went there. That is hendu. And, in this case, it was the institution that practiced hendu, because this was one of the main themes presented in the Pataxó group. The same has happened with the Puri, with the Guarani, with other indigenous people living in an urban context. That is why the museum, and its teams, have to learn how to listen.

And they need to include the body in this listening, don’t they? The bodies of people, but also of the institution.

They have to involve the body, because it both moves and moves the images, the voices, time itself. And the body is collective.

Accepting MASP’s veto of the images of Vilaron, Zinclar and Kanaykõ would be to exclude the bodies and struggles represented there.

When this veto came, we canceled the group, but before doing so we talked a lot. We did everything not to cancel Retomadas.

The biggest drama was when we also saw ourselves in this place of silencing, which is the practice of frightening and making the other vulnerable – something that has been happening to me within MASP since before Histórias brasileiras.

The ethical question posed to us was that most of the artists who participated in the group already came from places and stories of silence. Therefore, we could not go let this pass and accept collective silencing, which would eventually further weaken these artists. Not only the authors of the photographs, but all. The collective body.

And the collective body is not generic. It is not about the representativeness of the majority or the least relevance of the minority. I do not want to be generalized, I want to talk about an idea in several ways; I want to see various things, various aspects, various voices appear. I don’t want to be the focus of attention. I want other things to be seen.

You do not want to assert majorities but strengthen collectivities.

That’s right. When dealing with my image or the image produced by other people, I can’t think of the general. Collectivity cannot be a form of generalization.

In this process, you and the landless rural workers movement have always held the firm position that our struggle is a collective struggle. Both the indigenous struggle and the struggle of the social field of culture. Either the fight is collective or there is no fight. Individualizing the struggle would also produce vulnerability. It would be a way of facilitating the capture, something that appears in one of the scenes of the film Martyrdom (2016), directed by Ernesto de Carvalho, Tatiana Almeida and Vincent Carelli, when the police arrive and ask the Guarani Kaiowa people: “Who are your leaders?” and they answer something like: “All of us.” They do not focus the fight on a single representative and thus keep collective resistance moving, escaping capture attempts.

That is the Guarani way – to dodge and swerve. A mode of resistance that we learn from when we were children through dance. By dancing, we learn to move. When we move, we learn to dodge, and so we survive everything and all who, for five centuries, have tried to kill us.

If we want to protect our images, protect the spirits that the images try to capture, we have to put them in motion. It never seemed so important to me to move the images.

And we move together with them.

That is why Retomadas continues. The photographs walk with us, we walk through them. Everything is moving. ///

Conversation held in september 2022

CAPTIONS p. 131: Alessandra Munduruku in the 2a Marcha das Mulheres Indígenas: reflorestamentes, corpos e corações para a cura da terra [2nd march of indigenous women: reforest-the-minds, bodies and hearts to heal the land], by Edgar Kanaykõ Xakriabá. Brasília, DF, 2021. p. 133: 2a Marcha das Mulheres Indígenas: reflorestamentes, corpos e corações para a cura da terra, by Edgar Kanaykõ Xakriabá. Brasília, DF, 2021. p. 135: Mulher, mãe terra, MST [woman, mother earth, MST], by André Vilaron. Pontal do Paranapanema, SP, 1996. p. 137: Marcha das Mulheres, MST [march of the women, MST], by André Vilaron. Pontal do Paranapanema, SP, 1996. p. 139: 5th Congress of the Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra (MST) [landless rural workers movement], by João Zinclar. Brasília, DF, 2007. p. 143: Marcha Nacional pela Reforma Agrária (MST) [national march for agrarian reform], by João Zinclar. Brasília, DF, 2005.

Sandra Benites (MS, 1975) is an educator, researcher and healer of the Guarani people. She holds a degree in intercultural studies of the indigenous people from the south of the Atlantic Rainforest by Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina (UFSC) and a master’s degree in Social Anthropology by the National Museum, UFRJ. She is an assistant curator at Museu de Arte de São Paulo (Masp), where she produced the Retomadas group of the Histórias brasileiras exhibition (2022).

Clarissa Diniz (Recife, PE, 1985) is a curator, writer and professor. She graduated in Visual Arts from Universidade Federal de Pernambuco (UFPE), holds a Master’s degree in Art History from Universidade Estadual do Rio de Janeiro (Uerj) and is a PhD student in Anthropology at Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). She held the exhibition Raio-que-o-parta: ficções do moderno no Brasil [go-to-hell: fictions of the modernity in Brazil] (Sesc 24 de Maio, 2022) and coordinated the group Retomadas of the exhibition Histórias brasileiras [Brazilian stories] (Masp, 2022), among others.

Originally published in ZUM Magazine #24, April 2023