An exercise in perspective

Publicado em: 4 de September de 2018The interweaving of video and photography in performance art in the 1970s contributed to the debate on identity, gender and the body, and brought to the fore works by female artists. In 1974, American theorist Rosalind Krauss proposed the psychoanalytical hypothesis that the speculative potential of video also includes the possibility of autoerotic exploitation. In 1976, the American critic Lucy Lippard saw the work of Martha Wilson as deconstructing the myths of feminine beauty. Wilson, an American artist working in Canada, used photography to catalog parts of her body and presented performances in which she walked down the street with her face painted red. More recently, the work of American theorist Judith Butler has begun to inform a series of readings and rereadings of the performances of women artists. The interest in masquerade and in photographic-performative strategies of gender deconstruction has renewed attention to the seminal works from the 1920s of French artists Marcel Duchamp and Claude Cahun.

In Brazil in the 1970s, video art catalyzed the energy of artists interested in questioning their sociocultural identity.

Letícia Parente and Anna Bella Geiger explored, each in their own way, the construction of Brazilianness, Brazilian iconography and their own position as artists and women. Parente’s work focused most strongly on the quotidian and the private universe, while Geiger was more concerned in the major representational systems – the ethnographic eye and the cartography.

PHOTOGRAPHIC PERFORMANCES

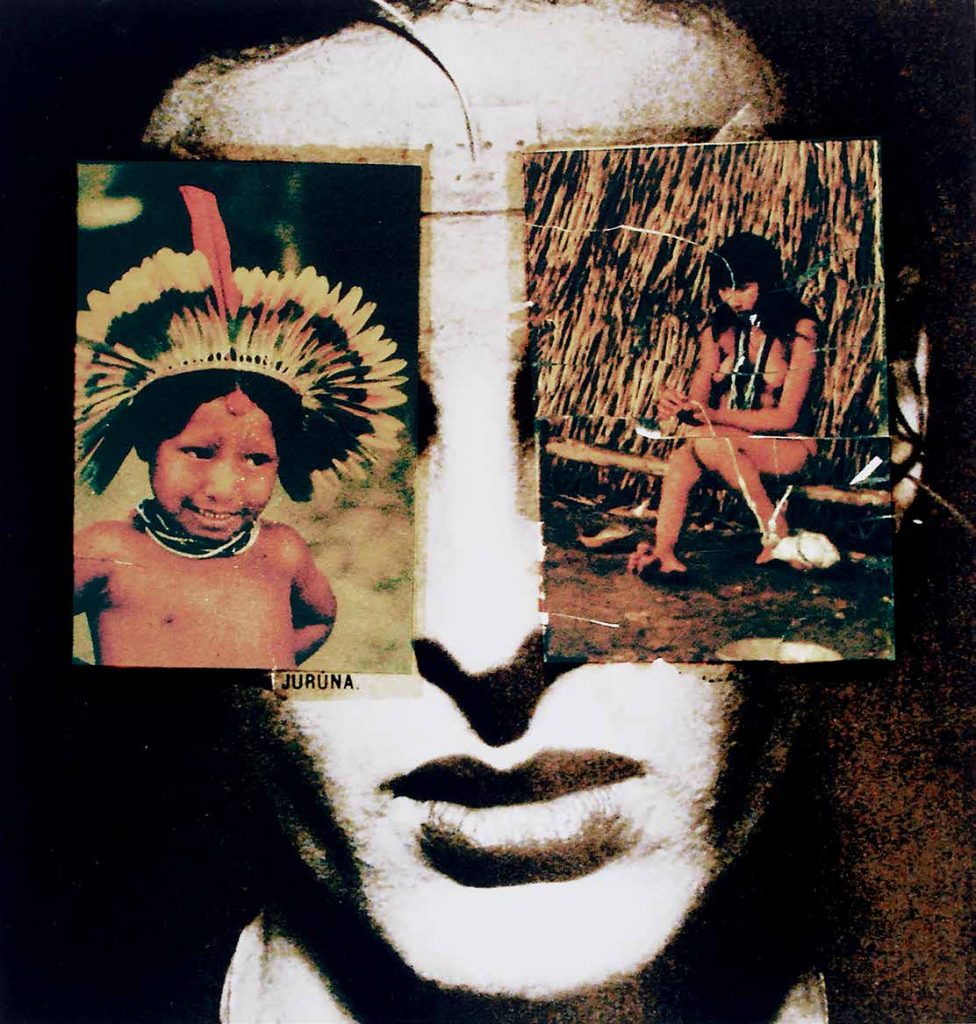

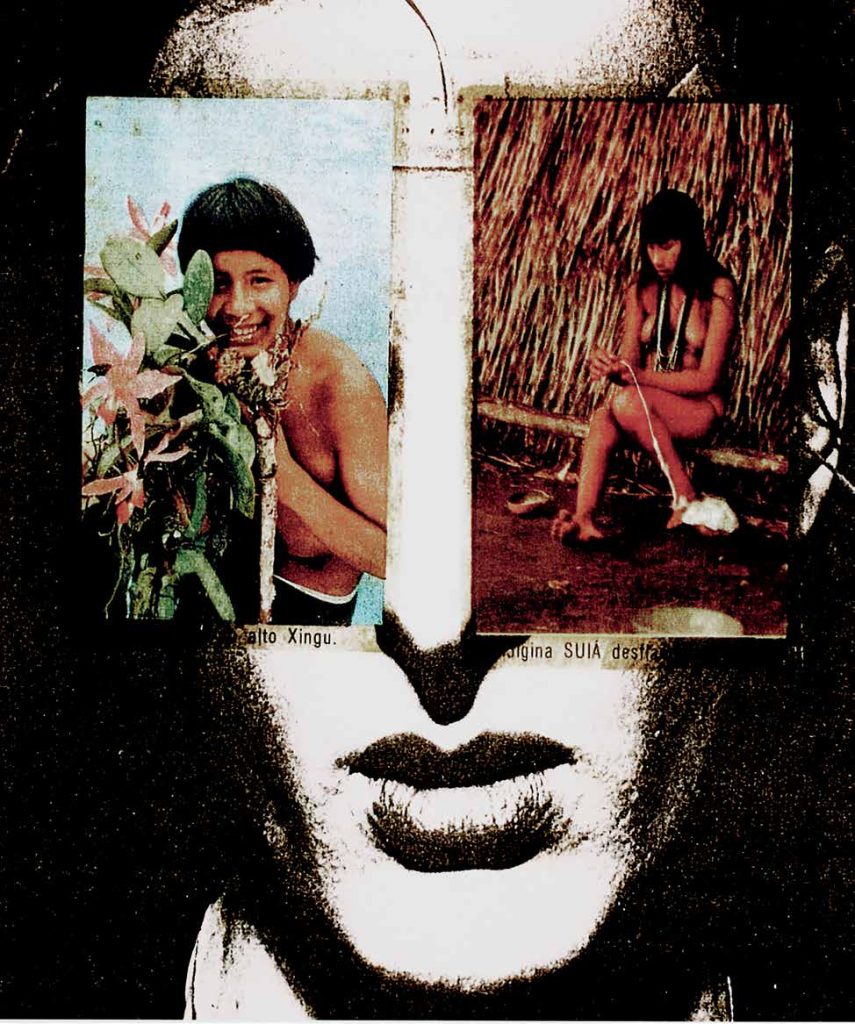

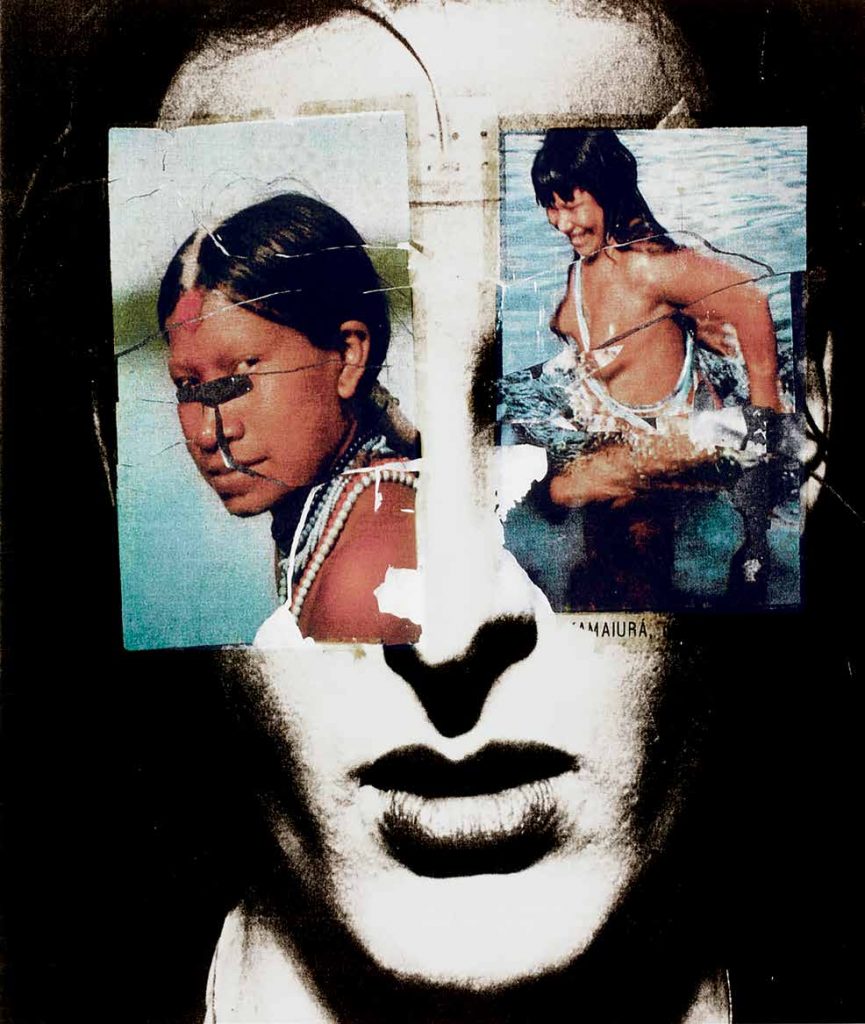

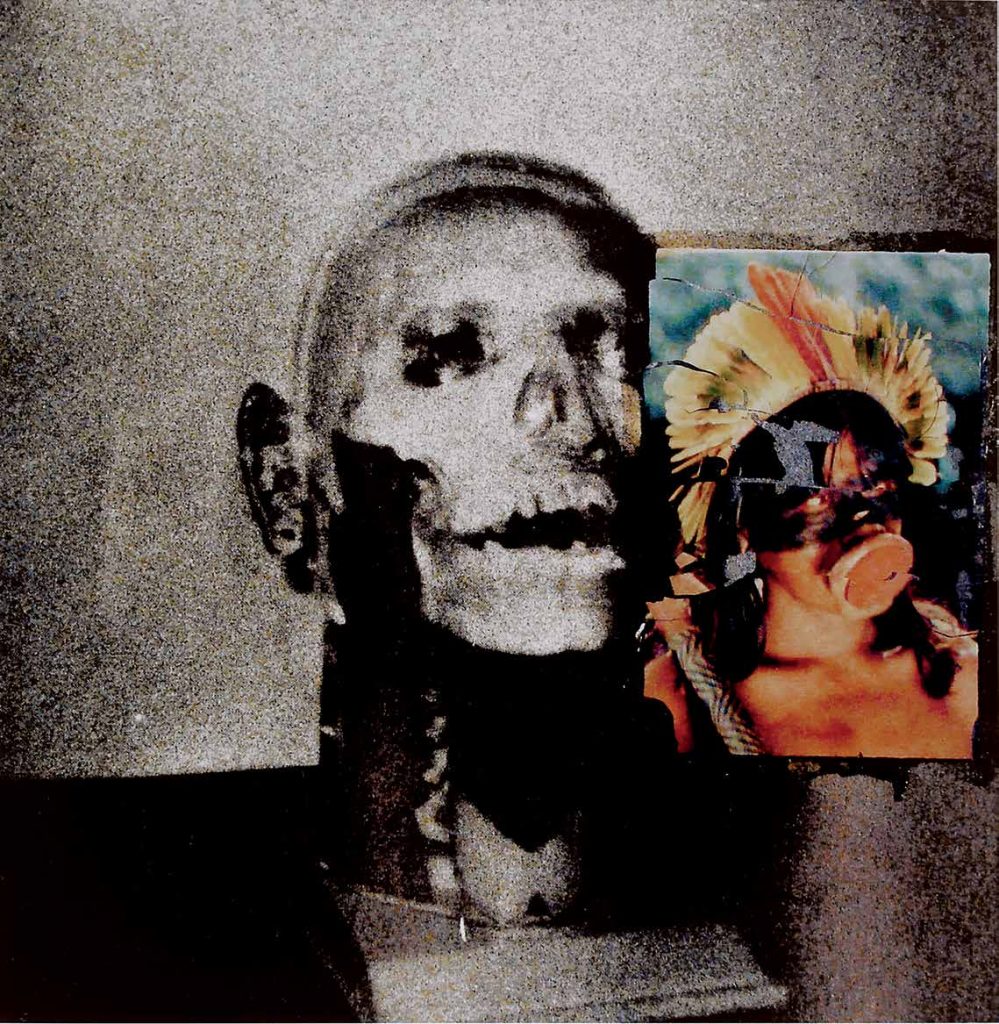

In her works History of Brazil (1975-76) and Native Brazil/Alien Brazil (1977), Geiger reflects on the country through feminist and Native Brazilian eyes. They are theatrical performances in which the image is a criticism of the flawed and mistaken representation of Brazilian identity. Geiger’s work focuses on the control of the historical ideal and on the space between identity and self-representations. Indeed, she also questions the Modernist versions in which the attraction for the native weighs strongly, though not necessarily as primitive or wild. The primitive ceases to follow a fixed chronology and becomes a force that erupts in the present. Thus, the native origin is filtered by the malicious eye that views the contemporary artist as a lucid and playful faux-naïf.

Photography unfolds in the relationship between the eye and the limitations to its reach; in the paradox of wanting to see and the impossibility of an objective view of what is seen. This is not a problem of interpretation or over-interpretation of something complex, but the ethnographic intention of the image and the area of blindness created by the viewer. The work intervenes in the cognitive system that supplies us with the images of the world that we consume and incorporate as “ours”. It operates more through tension and the creation of provisional senses than by establishing definitive answers to the questions raised. In each work we are faced with a new visual mechanism that shakes our faith in the usual ways in which we interpret and understand images.

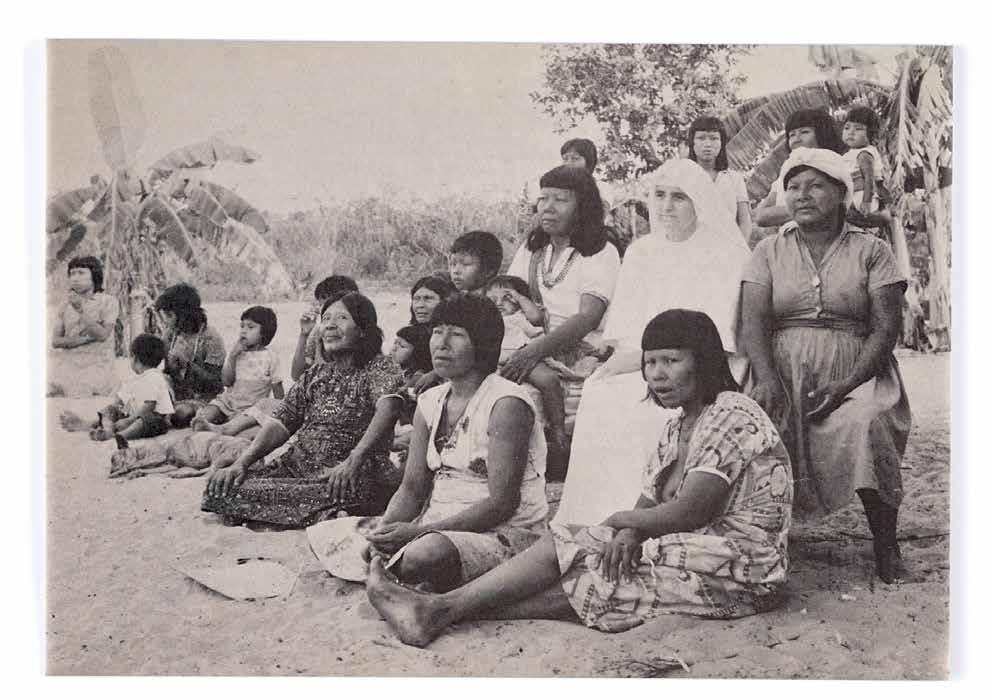

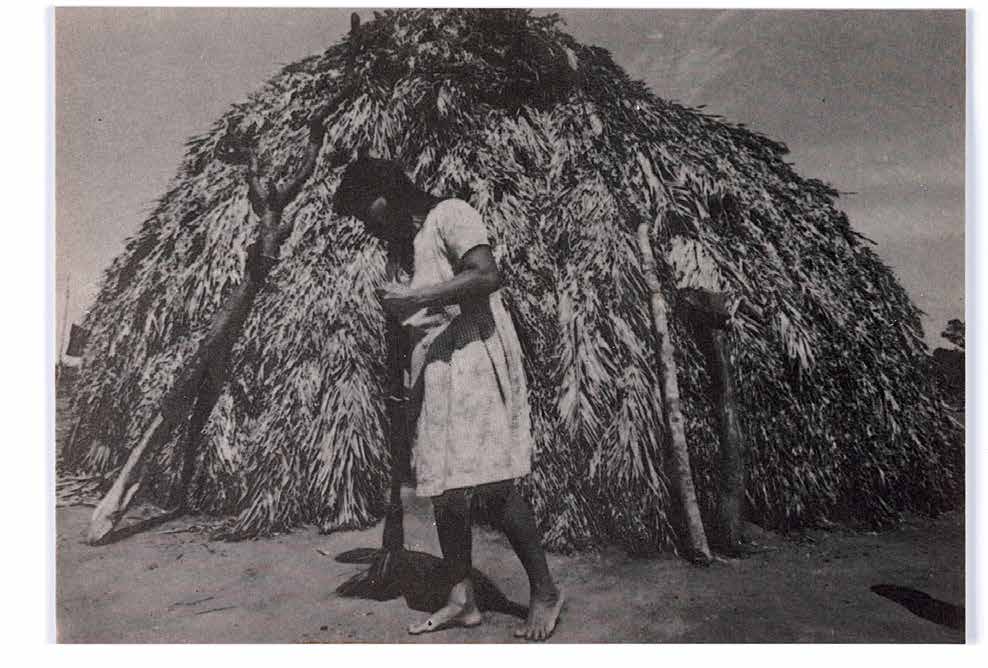

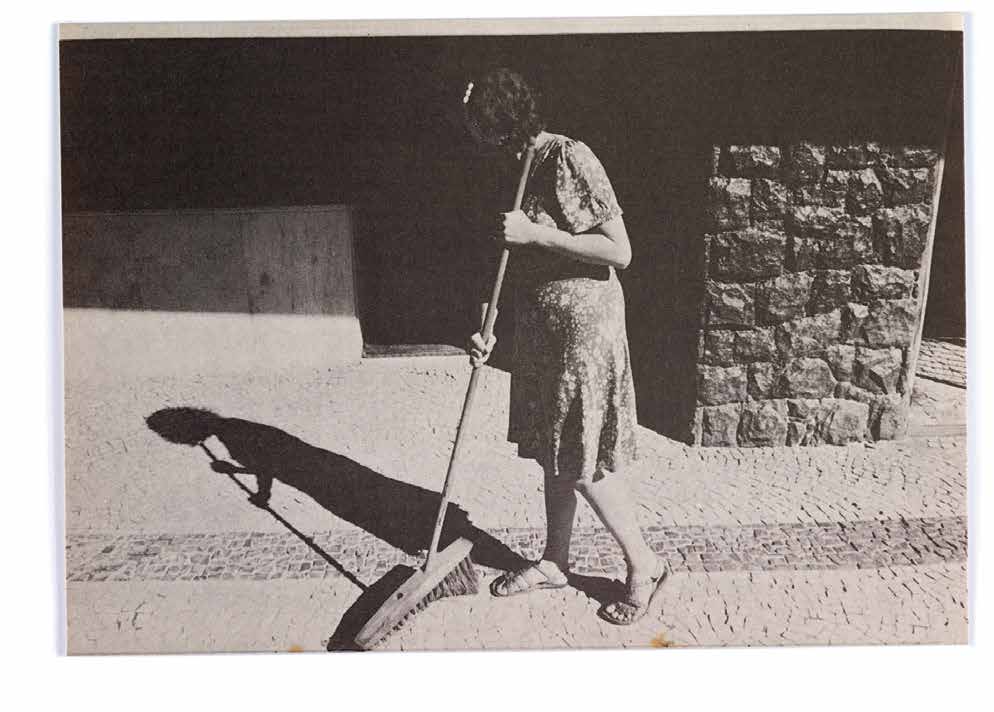

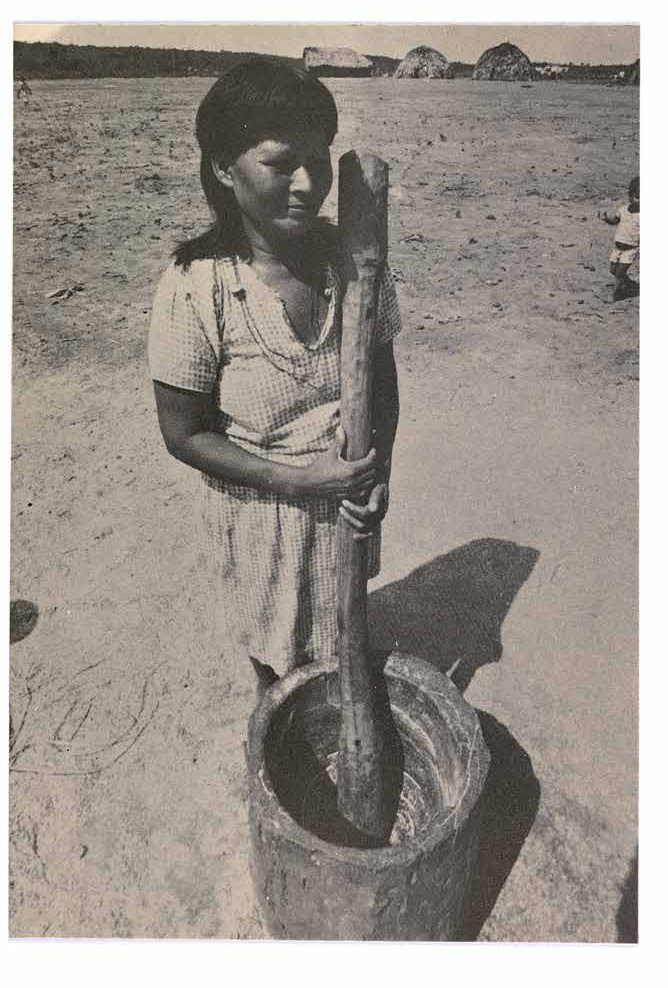

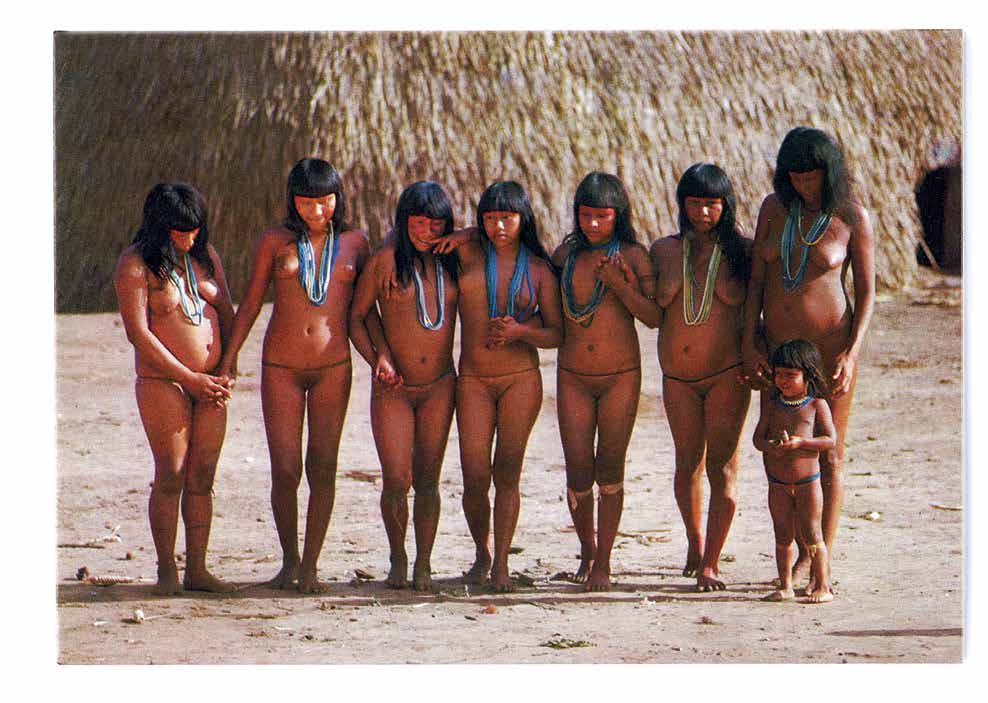

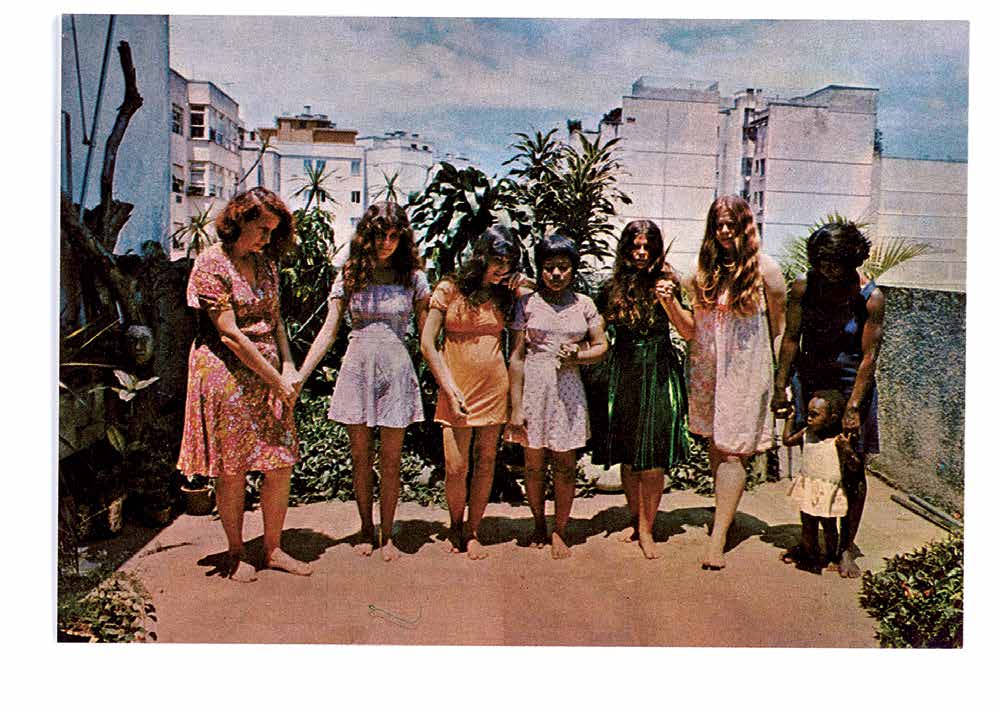

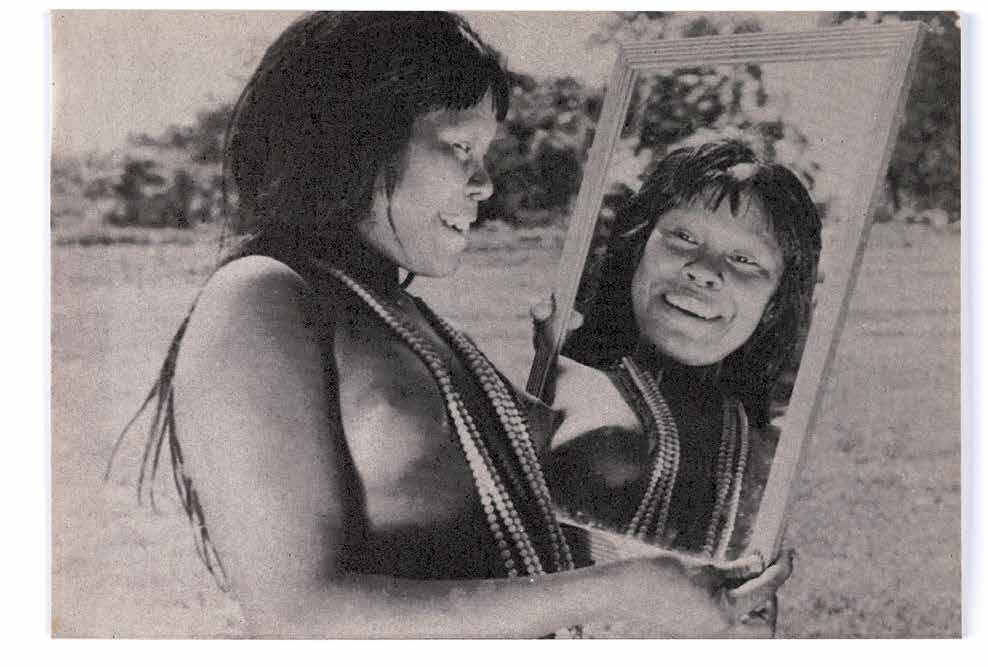

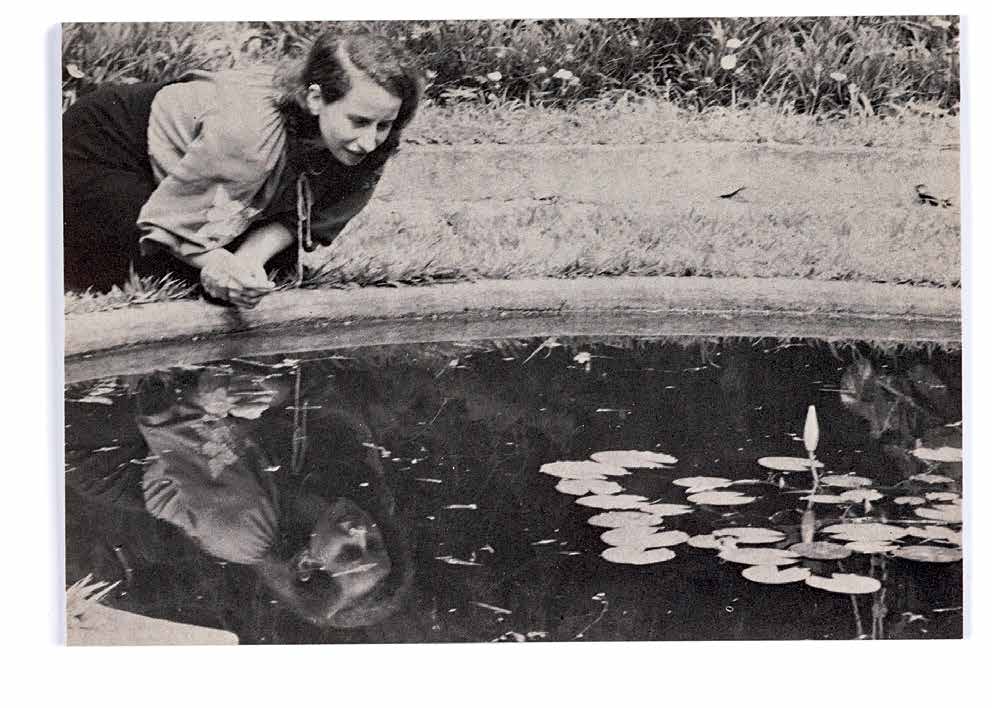

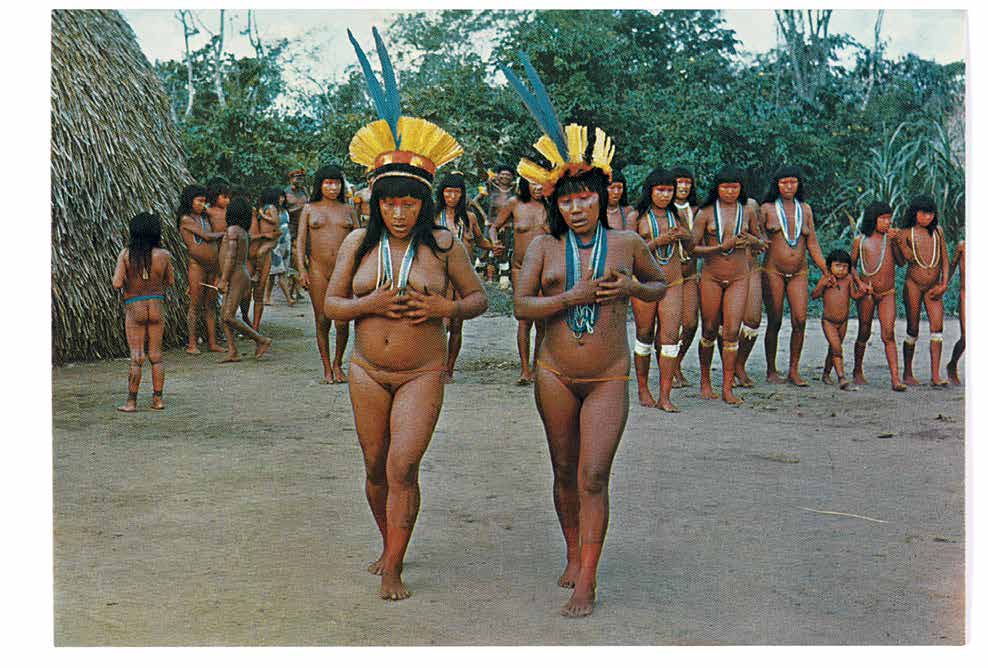

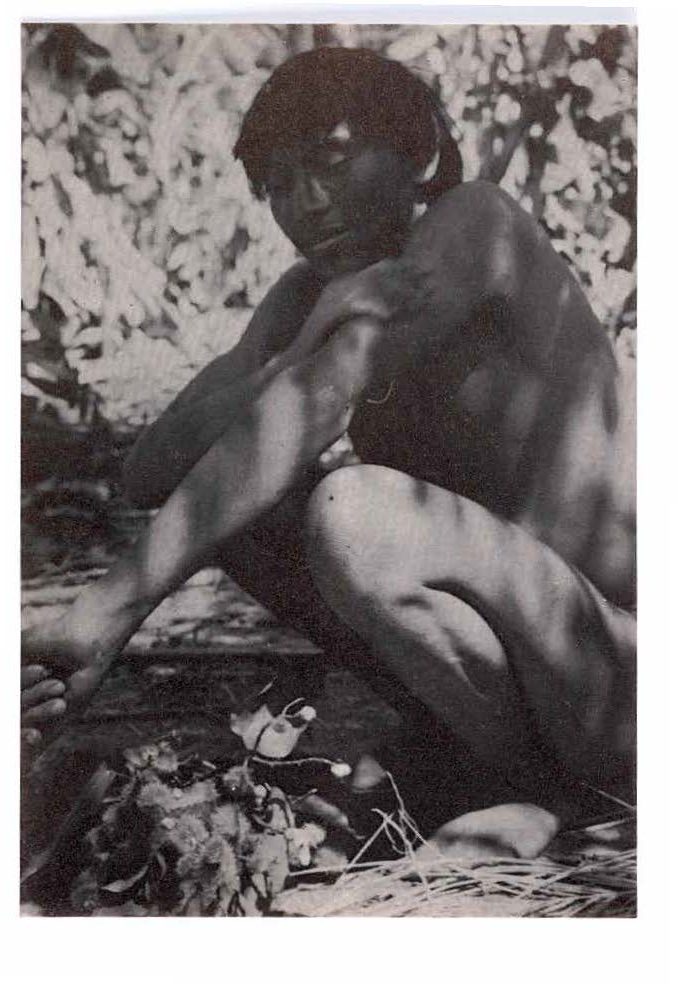

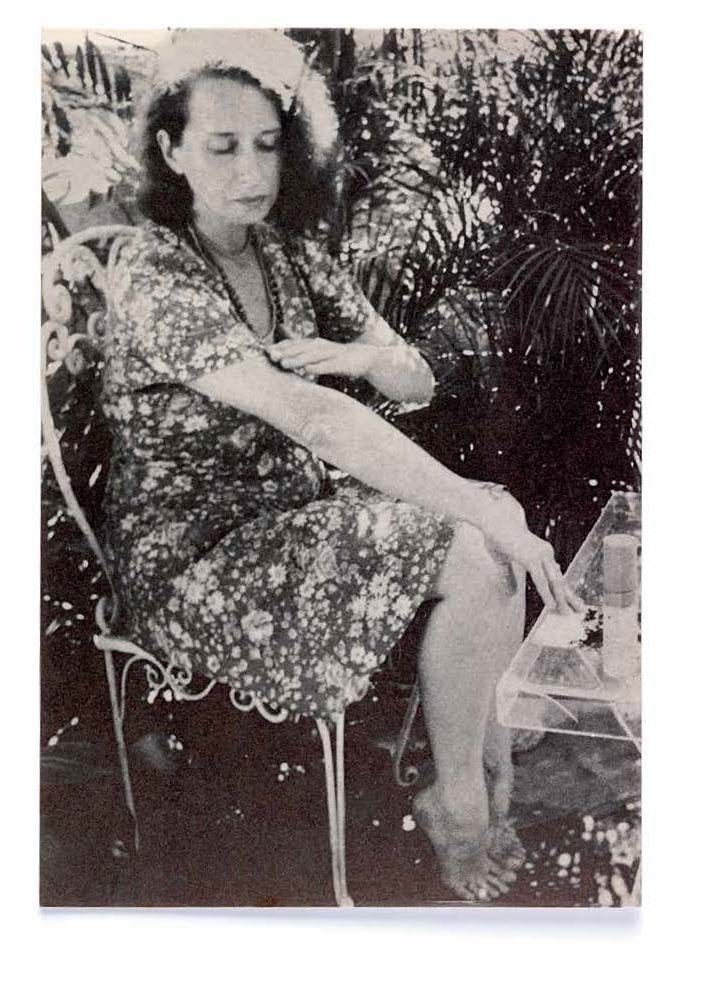

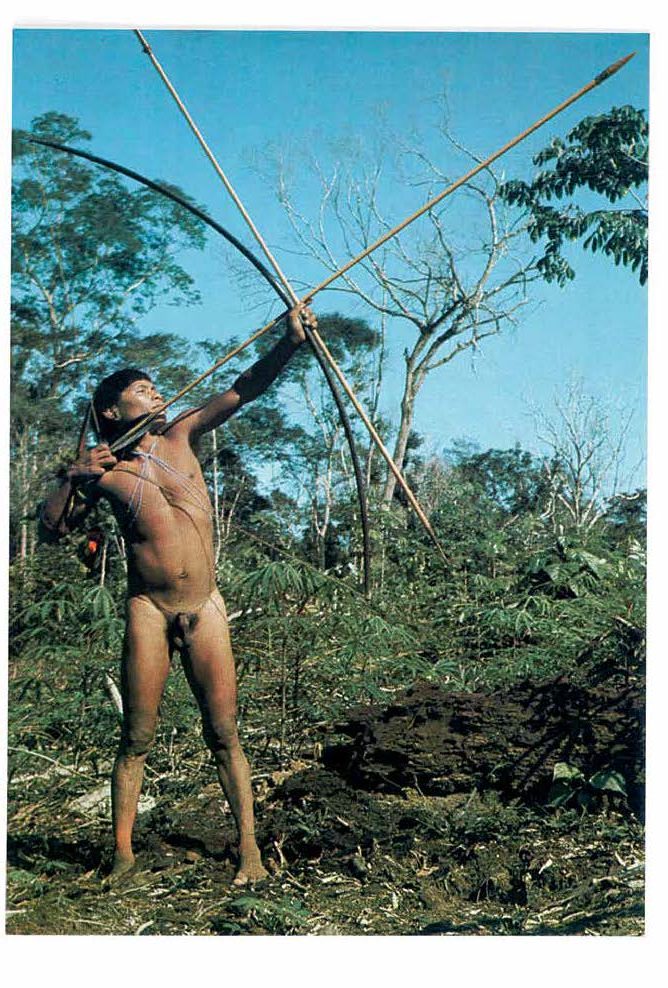

In Native Brazil/Alien Brazil Geiger appears in the photographs, clumsily mimicking the natural and everyday gestures of indigenous women and men. She appropriates a series of nine postcards entitled Native Brazil, which portray indigenous culture, and matches them to her self-portraits, creating nine pairs of images. The postal system and the materiality of the postcards were the objects of important interventions in the 1960s and 70s, yielding Regina Silveira’s thought-provoking series Brazil Today (1977), and Paulo Bruscky’s series No Destination (1973-83), in which he intervenes between the sender and recipient. In appropriating the postcards, Geiger avoided the condescending paternalism of folkloric or ethnic representations of native identity. The photographs, in this case, reveal her implacable examination of clichés, however well-intentioned they might be. She, an alien artist, reveals the Brazil that tries to overcome the vacuums of its representation and confronts us with the failure of the visual discourse attempting to fill that space, frustrating any pacific display of images that are supposedly emblematic of the nation.

If Geiger’s irony generates discomfort and amusement in the viewer, it is because it demonstrates that the concept of national identity carries with it the sterile fetishes of oversimplification and ideological assumption. With her artful appropriation of the image of an Other, Geiger casts a corrosive eye on the position of the artist in the history of the image. Her works thematize the point-of-view; the gaze itself is under examination. These series of photographs sustain an artistic gaze that does not submit to the stereotypes of Brazilianness generally accepted in mainstream artistic-intellectual discourse as its preferred mode of self-presentation.

Geiger uses photography as an inscription, an interstice, a passage, a journey. Removing herself to some extent from the 1970’s tendency towards active participation by the artist herself in the artistic experience, Geiger positions herself alone in front of the camera. Her work frees photography from its mission to capture time (lost) and becomes a tactic to confront the common way of seeing by applying seemingly simple maneuvers – juxtapositions, contrasts, assemblages.

Her photography puts the national anchoring of her artistic production under suspicion – what it means to be an artist, white, a woman, of European and Brazilian descent. It is, therefore, a reflection on the alien aspect of whiteness in a discourse that, historically, oscillates between two views of miscegenation: as a defect to be purged, and as value to be encouraged. If the subalterns cannot speak, as the Indian scholar and literary theorist Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak maintains, in the visual affirmation of Brazilian identity they appear as stigma representative of what is excluded. How do Whites establish a relationship with the Natives? What kind of relationship does this contact produce? Geiger raises these fundamental questions, but her answers are dilemmas, a non-relationship.

THE IRONY OF THE PHOTOMONTAGES

While in the 1970s the American artist Barbara Kruger used the graphically striking imagery of advertising, Geiger worked with materials and references from ethnographic photography. They both intervened in visual culture and used art as a discourse to challenge and disarm the then-prevalent reading of the images.

For Kruger, the combination of photographs and words has “the ability to determine who we are, what we want, and what we become.” If Geiger’s engravings from the 1960s such as Ear Cleaning with Swab (1968) already demonstrate irony, in her photographic series of the 1970s her irony became richer with its subversion of the link between invisibility, power, and the image. Her work becomes a provocative and disquieting reflection on the visual fantasy in which we are immersed and in which the artist is irredeemably involved.

Geiger’s collages are not intended to be explanatory. On the contrary, they make explicit the difference, the discontinuity, the disjunction, the impossibility of identification and of a universal visuality. Her self-portraits are broken mirrors in which elements combine without creating an unequivocal totality. As in History of Brazil, where the face of the artist in black and white, her eyes covered by colored photographs of Native figures and their adornments, speaks of an impossible communion. In contrasting herself with images of Native women, Geiger makes explicit the gap between the visual discourses affirming Brazilian national identity and the reality of Brazil, where the white culture is the parameter which defines the value of nativeness, sometimes attributing it with an opportune and romantic cultural positivity which crystallizes it as a museum object, sometimes excluding it and rendering it invisible as part of a view of Brazilianness into which it fits only as a fossil memory.

The visual depiction of nativeness and the ways it is expressed in national discourses provide the background to Geiger’s series Native Brazil/Alien Brazil and History of Brazil. The photomontages simulate ethnographic photography, which are normally consumed as legitimate and transparent manifestations of cultural facts.

NATIVE AND ALIEN

The Native and the urban White Alien of European origin have distinctly different views of belonging, in relation to the repertory of images of Brazil. To be a Brazilian artist is to live with a tension created by differences, not erasing them and without recourse to the comforting naiveté arising from their privileged position. The concept of nativeness and its essential relationship with cultural spontaneity is called into question in these works. For the anthropologist Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, “what makes a native a native is the assumption by the anthropologist that the relationship with his or her culture is natural; that is, intrinsic and spontaneous and, if possible, not reflexive; better still if unconscious”. It is precisely against this idea of nativeness that Geiger’s work position itself. It is in support of that position that the juxtapositions of Native Brazil/Alien Brazil speak of a Brazilian myth or fable which sustains the native as the object of an alien gaze. What Geiger does with her caustic wit is to portray herself from the same position – transforming Whites into the Aliens.

“The anthropologist usually has an epistemological advantage over the native,” Viveiros de Castro reminds us. “The discourse of the former does not consider itself as on the same plane as that of the latter: the understanding that the anthropologist develops depends on that of the native, but it is he who holds and controls that understanding – who explains and interprets, translates and introduces, textualizes and contextualizes, justifies and gives meaning to that understanding. […] In fact, as Geertz might have said, we are all natives now; but in law, some are always more native than others.”

But what strategic advantage does a visual artist have over the Native? They may show images of the Native without their knowledge, perhaps as a nostalgic icon of the idea of belonging to nature, perhaps as an emblem compensating for colonial violence. In blindfolding the eye of the White woman with ethnographic images, however, Geiger suggests the extent to which this vision is artificial, sustained by projecting an image in which the other is merely the reflection of an idea, upon which the artist depends to constitute herself as White and Western in a country that is marginal and poor.

Geiger touches, perhaps with skepticism, the open wound that is the difficulty we have in exercising perspective. We see what we cannot see because of the ambiguous tangle of dependence, distance and asymmetry between the Native and the Alien. With a few basic resources, Geiger creates a radical tension in her representational approach, where it is as if the simultaneousness between seeing and representing has been sequestered and all that remains for us to say is what we do not see and look at what we cannot say. We are only able to represent the Native without seeing him. The Native never sees himself as Native and is therefore fated to be the alien of the alien, eternally the other of their complementary other, the White alienated while sustaining a Western gaze.

In these works, native and alien are not antagonistic figures, but concepts supported in an addictive reciprocal relationship exposed by the performance. On the one hand, and perhaps contrary to the twin contradictory promise suggested by the title, the native and the alien are some degrees away from a certain ideal of authentic belonging to, or at least authenticated by, the dominant culture – that of the Whites. On the other hand, the alien is not “of the land,” which might explain the alien obsession with cartographic forms of recording and by the poetics of the geographical imagination. While the native is being spoken of and seen by the alien, this situation maintains the possibility of narrating its own fictional tale of belonging.

We are all aliens, because we are separated by language, but we are also all natives because we inhabit the Earth. It is not that Geiger promotes a utopian spiritualism or preaches the harmonious coexistence amongst peoples; on the contrary, her work impacts on the myths of Brazilianness forged by our Modernism, even in its more skeptical and pessimistic versions. If the Modernists still believed in building models of interpretation of the Native, Geiger uses photography to emphasize our own cognitive limitations. The tragedy of these images is that they reflect on an imprisonment for which they do not offer a solution: the visual operation in which the alien is trapped depends on the consumption of the image of the native. The ethnographic image becomes a gesture of the humanist validation of otherness. ///

Anna Bella Geiger (1933), from Rio de Janeiro, taught at MAM-RJ and Columbia University, New York. She is co-author of Geometric and informal abstractionism: the Brazilian avantgarde in the fifties (1987), with Fernando Cocchiarale.

Laura Erber (1979) is a writer and visual artist. She teaches Theater Theory at Unirio. She is joint managing editor of the digital publisher Zazie, with Karl Erik Schøllhammer.