The Political Image

Publicado em: 24 de July de 2014The different ways ANTONIO MANUEL uses photography in his work.

IN HIS RECENT EXHIBITION at the Museum of Modern Art in Rio de Janeiro (December 2013 to February 2014), Antonio Manuel showed two new installation works, one of which entitled Até que a imagem desapareça [until the image disappears]. For many years he focused only on abstract painting and not on the photographic image, but now he has rediscovered it. However, he did so only to see it disappear again over the two months of the show, slowly washed away by drips of water, which were caught in a container placed on the floor. The disappearing images were taken from his older work and the development tank, in which the photographic print was immersed to reveal an analogue image, here worked in reverse: damaging, blurring and finally dissolving the image.

Originally a newspaper photograph, which was then copied and erased into one of three containers, the main image belongs to his now classic series Repressão outra vez – Eis o saldo [Repression Again – Here Is the Consequence] (1968), where we see the police chasing students through the streets of central Rio. The artist’s original statement heading the silkscreen image now gains a suggestive question mark: “Repression again?” Can it be that, after almost 50 years, the remaining disturbing memories of an authoritarian past have not completely healed? How not to repeat that past? What is the role of art in describing the past and how does it help us to label it, hold on to it and change it? What is the place of the image in the work of Antonio Manuel and how has it unfolded over time?

In the interview “What Do Philosophers Dream of?” (1975), Michel Foucault describes his interest in painting, with its invitation to look and the pleasure it gives. At one point, talking about painters who were contemporary with him, he observes that what pleases him most about their work is their determination to restore the place of the figurative image after a long period when the genre was sidelined. This revival of figurative work also had an impact on the work of Brazilian artists, such as Antonio Dias and Carlos Vergara. In both the Northern Hemisphere and Brazil, this renewed concern with the figure was linked to an urgent political agenda, which was not interested in a utopian future but was driven by the need for direct action on real and present problems. Art reaffirmed its concern with the present and was affected by the cross-currents of the political conflicts of the time.

And in this respect, there were signs of resonance with popular culture: the first signs of a globalised aesthetic spreading out horizontally amongst the insurgent youth. Blurring of the edges between high and low culture gave strength to the desire to merge the artistic impulse with the vital energy penetrating from the world outside the museums. The negativity, which was so much part of the modernist disconnect between artistic experimentation and mass society, turned into a critical statement which was admittedly – and simultaneously – contradictory and dissonant. And it is not a coincidence that the following was to be read at one of the entrances to Hélio Oiticica’s installation Tropicália (1967): “Purity is a myth.”

The Newspaper as a support

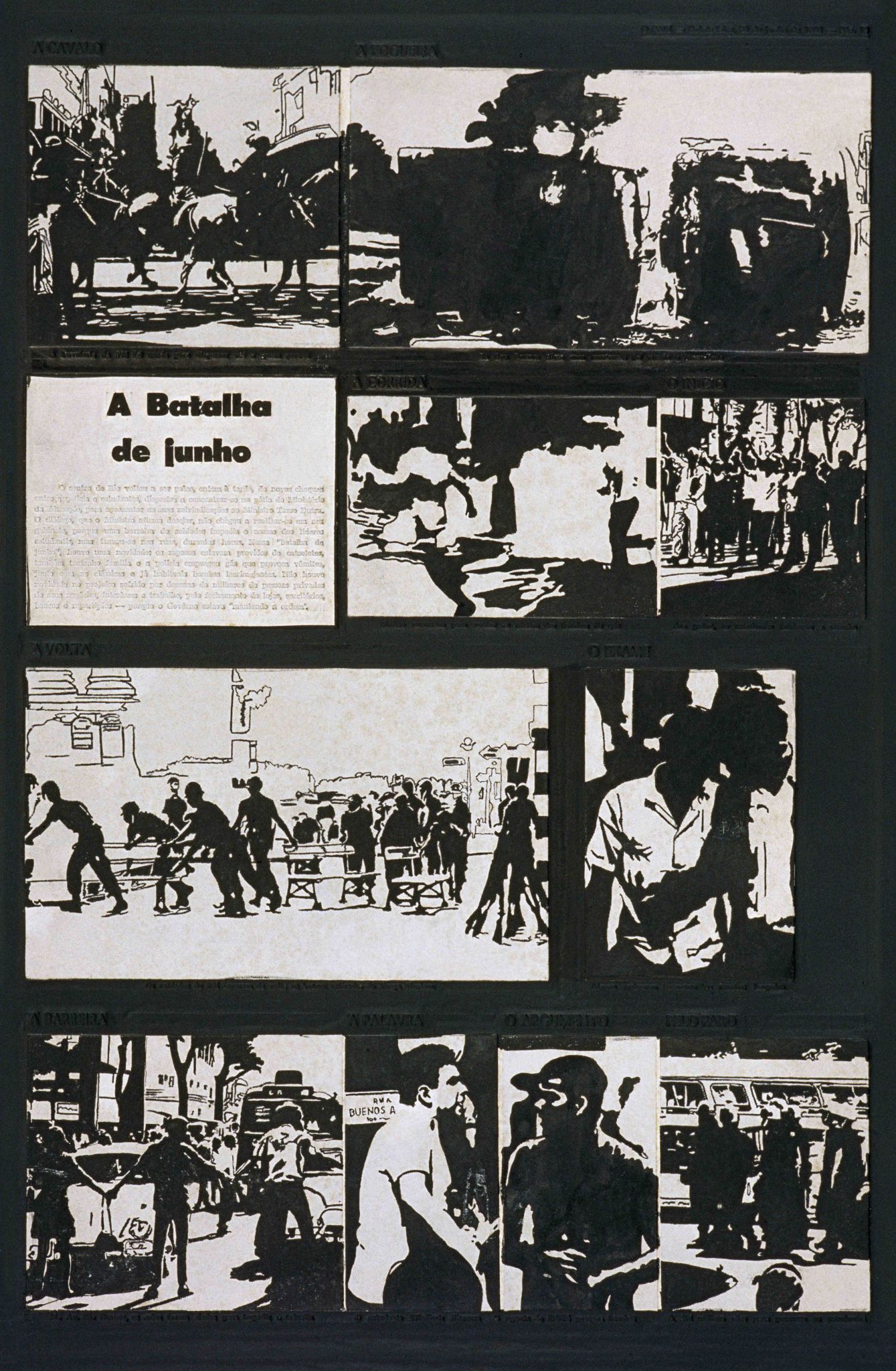

At that same exhibition where Tropicália was shown – New Brazilian Objectivity (Museum of Modern Art, Rio de Janeiro, 1967) – Antonio Manuel, invited by Oiticica himself, exhibited his first series of drawings overlaid on pages from newspapers. Interfering directly on the pages, he drew on top of the original images of news stories and photographs, creating a multitude of anonymous figures, devoid of individual identity but given collective power by the intervention. His use of newsprint emphasises his working canvas – soaked with meaning, dirty, full of ephemeral, mundane information, deliberately public and clearly political in its intent. And it is from this visually noisy surface of text and images that his crayon brings forth a multitude of expressive beings, each with their own unique graphic identity.

Restoring the dignity of the image in the 1960s did not mean a return to order, or to the contrast between figurative representation and the experimental impulse of the modern tradition. On the contrary, it was an appeal to what had been repressed in the cleansing process to which the visual arts had been subjected the desire to give the figure the same emotional charge that the sung word had given to Rock music. The image was a call to participate, short-circuiting a path between identification and de-identification. What was seen was recognisable but did not look like anything commonplace. At that moment, a rebellious impulse was born. As noted by German critic Benjamin Buchloh, “in 1963, Warhol juxtaposed the most famous photographs of glamorous movie stars with anonymous and ruthless images of everyday life (which had been rejected by the photo archives of the daily press).”

What is a car accident doing as part of the symbolic vocabulary of the visual arts? How can it be shown next to an image of multiple bottles of Coca-Cola or a picture of Marilyn Monroe? How come a drawing over a sheet of newspaper be considered art? Would the everyday image be capable of displacement, of becoming amazing and inspiring? This indirect dialogue between the works of Antonio Manuel and Andy Warhol still lacks a critical study. Despite the different contexts and disparate motivations, some points of contact can be found, namely the use of collections of press photographs, the simultaneously pictorial and ready-made status of the image, the critical appropriation of criminals, the watchful eye focused on the margins of society, and the use of unconventional devices in the visualization of the work. The direct confrontation with a dictatorship gives the poetics of the Brazilian artist a more dramatic and less cynical tone.

The work of Antonio Manuel is often divided into two phases: the first, which started in the 1960s, is marked by political action and performance works, while the second, from the mid-1980s onwards, has paintings concerned with constructivism, labelled as formalist and so de-politicised. His move to geometric abstraction followed the path of Brazil’s progress towards democracy, in which political voices retook the public stage after their exile. This choice also appears as a kind of reaction to the return to popularity of figurative paintings, which seemed to have been born already excessively concerned with the demands of the market.

Looking closely at how Antonio Manuel’s poetics developed, from the very beginning we can find an articulation between the political and the formal that discredits this strict division into two distinct periods. The journey from his drawings on newspaper, in 1966 and 1967 – which were selected for acquisition by the São Paulo Biennial in 1967 – to the Flans series already shows a concern with structure, formality and a close dialogue with the Brazilian tradition of concretism. It is not mere chance that many of the Flans were taken from the Jornal do Brasil, a daily newspaper which Amilcar de Castro had revived in the 1950s with an open and orthogonal layout that gave space for Manuel’s artistic interventions.

The flans – laminated cards which served as a base to the production of lead matrices, used in the rotary printing of newspapers – were discarded after use. Antonio Manuel spent his nights collecting those which most interested him, politically or artistically. He then used talcum powder to highlight the image that he wanted to overlay, and traced it with ink. He always emphasised geometric structures and his drawing shifted the original images, giving them pictorial quality and political intensity.

His 1968 Flans document the street: they are images of urban violence and the student movement that resisted the dictatorship. Not only do they reveal the events themselves but they also overlay them with willingness to act and the need to take sides. This intervention anticipates much of the present work of Mídia Ninja. It is politics, art and action mixed together, it is a dispute to appropriate the image and to give it a narrative, which is in discord with the official version. Voices multiply and political subjectivities are formed by the confrontations in the streets. Lygia Pape wrote of Flans, under the pseudonym of Janaína: “The euphoria of collective moments. The collective as an emblem. Then the uniqueness, the anti-headline.”

Closed Curtains

In 1968, while he was working at the Museum of Modern Art in Rio de Janeiro on the exhibition to be shown at the pre-Paris Biennial 1969, Antonio Manuel used his Flans in a different way. Working with the artist Julio Plaza, he turned them into silkscreens with a red background, printed them on wood and hid them behind a black curtain, to be opened by the public at the exhibition as they passed by. Somehow, and rather ironically, with the increasing political tension in Brazil, the curtain succeeded in anticipating the wave of censorship that would intensify after the publication of AI-5 [the most restrictive decree issued by the Brazilian military dictatorship]. His premonition was acute: a certain General Montanha saw the work and banned the exhibition, which never opened to the public. The dictatorship kept the curtains closed, and the popular movement, repressed in the streets, ceased to have a symbolic space to express itself.

This game in the space between the revealed and the hidden, straining at the limits of what is permitted to be seen and moving these discarded images into the realm of censorship, was a constant factor in Antonio Manuel’s work during the most critical period of the dictatorship – between 1968 and 1975 – and he was to re-visit it later on every so often in other works. When, in 1973, Antonio had an entire exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in Rio de Janeiro censored, rather than accept the decision and turn his back on it, he sought ways to exhibit the works by other means, re-creating them in the Cultural Section of O Jornal, after long negotiations with the editor, Washington Novaes. This intervention- cum-exhibition would be called De 0 às 24 horas [from 0 to 24 hours], the length of time a newspaper remains current. The sixpage section reproduced the texts and images that were to have been shown in the museum.

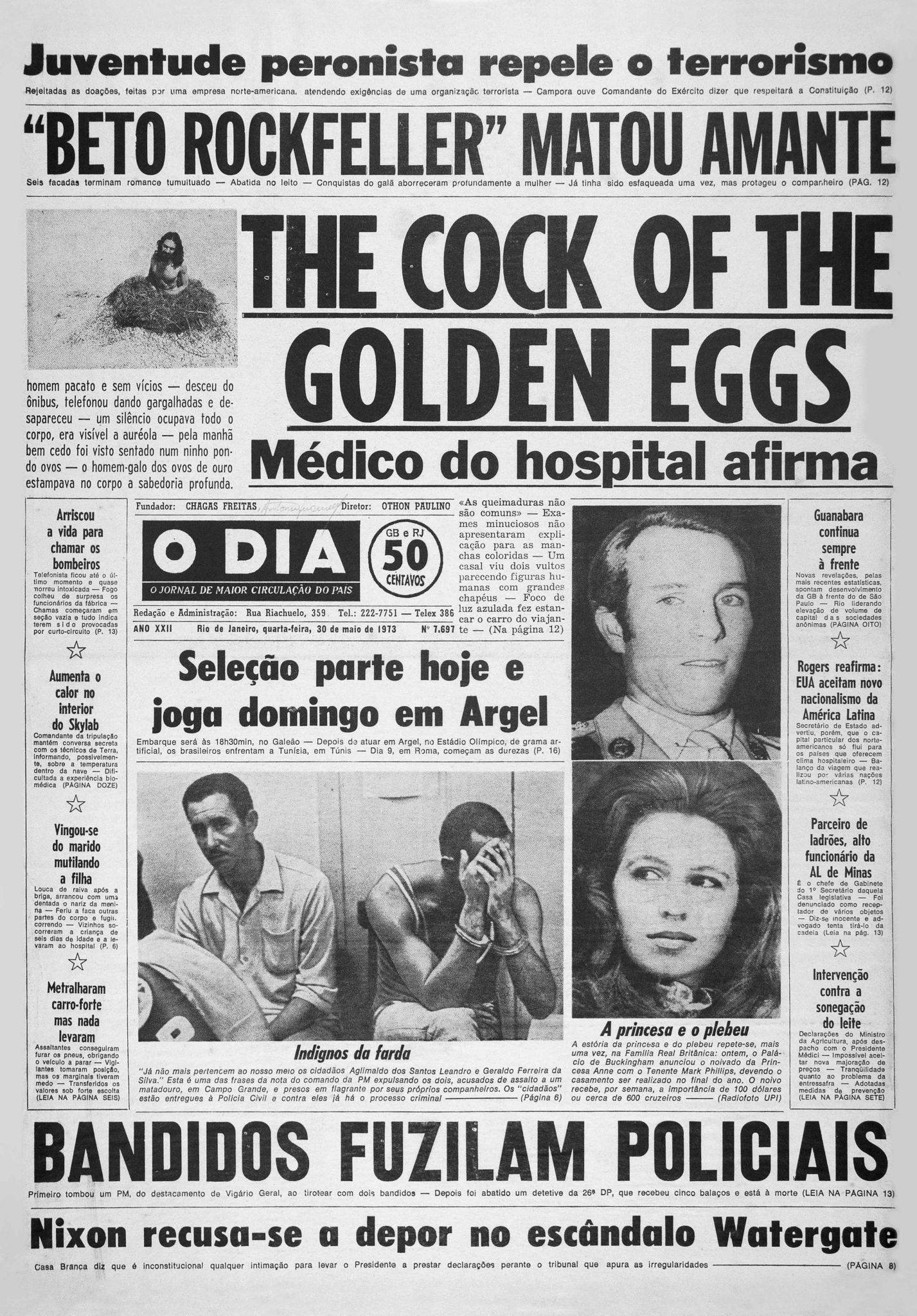

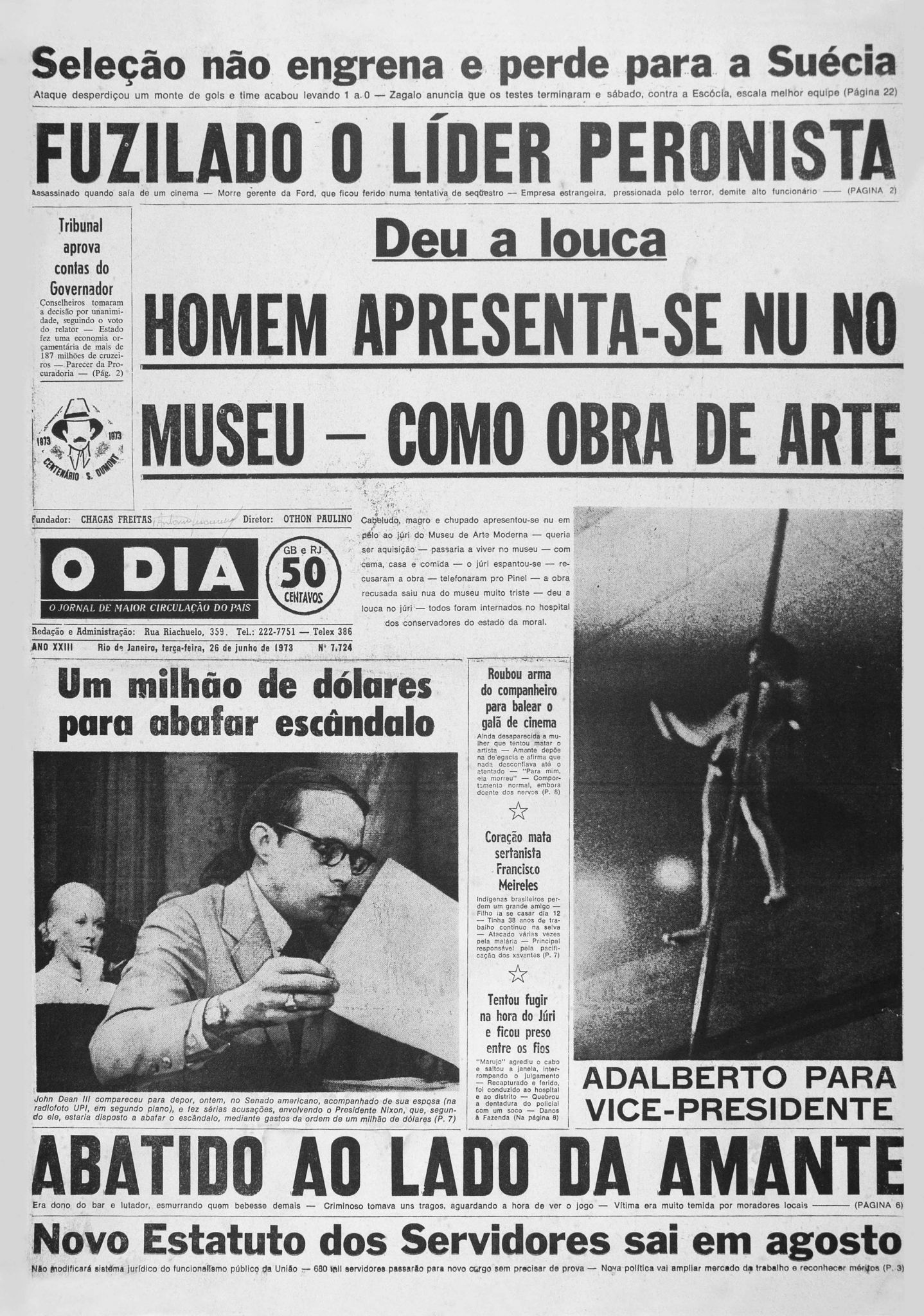

The image is both a witness and an intervention. Instead of being limited to mere factual documentation, it unfolds in other ways, unforeseen by those charged with controlling it. Formal decisions are allies in this process – notes Lygia Pape, “the graphic line is the foundation of the artistic medium.” The insertion of texts other than those found in the headlines starts appearing alongside the images and becomes decisive in his Clandestinas [clandestine] series (1973). The process was similar to what was used in previous Flans. But now he added material – images and text – always with strong poetic appeal: “Pintor ensina Deus a pintar” [painter teaches God to paint]; “Abajo el puerco intelectual” [down with the intellectual pig]; “Torquato Neto: Deus um clarão no salão / Poeta virou estrela” [Torquato Neto: God is a gleam of light in the lounge / poet becomes star]; “Línguas insaciáveis: sabor doce para bocas amargas” [insatiable tongues: a sweet taste for bitter mouths]. In Clandestinas, the artist inserts visual, graphic and textual material on the cover of a daily newspaper and prints it, causing even more of a disturbance by returning it to be sold in some of the city’s newspaper stands.

Throughout his work on this series, Antonio Manuel used the newsroom at O Dia, with the help of Ivan Chagas Freitas. It was no longer the flan itself that interested him and on which his work was based, but the act of manipulating the production of the newspaper and its clandestine circulation. It was possible for someone to buy “a work of art” on a newsstand quite unwittingly. This lasted until the newspaper’s owner, Antônio de Pádua Chagas Freitas, Ivan’s father and future governor of Rio de Janeiro, discovered the presence of the subversive artist in his editorial offices, producing false covers for O Dia.

Antonio Manuel also used the newspaper’s photo archives to find disturbing images of criminals who had been arrested and/or killed violently by the police and death squads. He made the experimental film Semi Ótica [semi optics] (1975) based on these images, with soundtrack by Guilherme Vaz. After each image appears, it is followed by a fictional police record, with the name, age and skin colour of everyone depicted. When giving information about colour – most of the photographs depicted black or brown people – he attributed them with weird, imaginary ones, such as half-green, half-yellow, half-black. They became mixed up, half-citizens, either blended or divided, highlighting the ethnic and social divisions that can no longer be hidden “optically” by skin tone. It was a semiotic critique of a society where a racially equal democracy remains a myth.

The Installations

From the 1980s some of his questioning of the photographic image and newspapers is given voice in his installations. Ronaldo Brito wrote about Fantasma [ghost] (1994), one of the artist’s most emblematic installations: “As a fundamental principle, an installation must take a certain public space to expose its aesthetic, cultural and political properties.” The act moves from the street and the newspapers into institutional spaces, while carrying with it the noise and stress of the world. While he was preparing this installation, the massacre at the slum Vigário Geral in Rio took place. The indiscriminate elimination of young, black underprivileged Brazilians – a subject already explored in Clandestinas and Semi Ótica – was now to be subtly incorporated into this installation. It consists of a maze of charcoal fragments, suspended from the ceiling. It also features a small photograph extracted from a Rio newspaper, pasted in a corner of the room and lit by two lanterns. The image shows a survivor of the massacre, his face hidden by a cloth, beset by microphones, giving a press conference. The beauty of the installation space, with its shadows and black silence, is dramatized by the burning of lives and the transformation of the witness into one more ghost created by the daily violence in society.

And this is where we should recall an installation from the mid-1970s, prepared for Venice, where the images of criminals used in Semi Ótica were enlarged, placed on the floor and covered by a black carpet, which could be lifted by wires hanging from the ceiling. These two moments, these two similar visual experiences, are both expressions of one fundamentally ethical revolt against social exclusion.

If the face of the massacre survivor in Fantasma was covered to hide his identity, it is the identity of the image itself that dissolves in two of the artist’s recent works, made for the exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. The memory of past works and the transience of newspaper news are now slowly smudged and erased. In a world bloated with images, could its breakup be the condition to any poignant expressiveness, to any possibility of conflict?

In Nave [ship] (2013), the cubicle composed by four empty door frames displays a video showing images from a short film. Over the screen, a hanging cloth bag slowly drips water that blurs the night shot of the streets of Rio, alternating with shots of a fire, fuelled by pieces of newspaper. As it happened in Até que a imagem desapareça, where remnants of his past works were slowly diluted by water, references to the streets and newspapers in Nave are the political space of his poetics, recreating itself under the dissolving action of water, fire and time.

In the opening scene of the film, two newspaper clippings are slid under a door and shown to the camera, as if they come from the past. One reads: “Affective memory.” It is this emotional memory that will be continually reset and undone in the video. For some moments, the focus is on a headline: the words “crisis in education” and “impunity” stand out. While in Flans the artist intervened in the newspaper and recovered a lost image to give it political significance, now he covers it, dissolves it away. No longer is it a call for action, but an introspective leap, a questioning – a political questioning – of the power of the image and the sort of action it can sustain.

Antonio Manuel’s hole in the walls, deletion of images, and empty screens are ways to question the bewildered state of the world. After nearly five decades as an artist, he has realised that the forms of representation actually represent very little, but he avoids falling into a nihilistic indifference – he deletes his images of the past to open up other areas for creation and other forms of action. The burning of newspapers on the fire and the dissolving of the Flans images are a release from the ways of the past, so that young people and the new technologies can devise their own political subjectivities. There is a history of the press and art, with its crises and political reverberations, to be written – from the work of Antonio Manuel to the interventions of Mídia Ninja. ///

reproductions: Flans series: Lula Rodrigues; Clandestinas series: Mario Caillaux

Antonio Manuel (1947) was born in Avelãs de Caminho, in Portugal, moving with his family to Rio de Janeiro at the age of six. In addition to his painting, sculpture, printmaking, drawing, installations, and performance art, he directed the short films Loucura & cultura [madness & culture] (1973) and Arte hoje [art today] (1976), amongst others.

///

Get to know ZUM’s issues | See other highlights from ZUM #6 | Buy this issue