Studio Malick

Publicado em: 14 de May de 2014For five decades, MALICK SIDIBÉ has been Mali’s unmistakable visual narrator. Still working from a simple studio, he has portrayed the effervescence of decolonization and a people rediscovering its identity.

WHEN IT COMES TO MASTERS of portraiture, many renowned photographers come to mind, such as Richard Avedon, Irving Penn, Philippe Halsman, and many others. And there are those who are revered for their portrayal of a people or a country, such as Robert Frank, Walker Evans and August Sander.

Through a set of circumstances that brought talent, chance and history together, the African photographer Malick Sidibé is a hybrid example. From a studio tucked away in the oldest district of Bamako, the capital of Mali, he set out to portray a complete era which, although compressed into a relatively short period, was that of a suddenly independent country, of a people resuming its identity and of euphoric youth striving towards the future.

Mali was once the proud cradle of an ancient civilization. It was attacked, conquered, abandoned and retaken countless times throughout its history. After centuries of subjugation, the Malians, a people made up of 26 ethnic groups, got used to being defined by those who were in charge of their very existence. Mali was a French colony for 80 years before its independence in 1960, when it was caught up in the whirlwind of decolonization that swept Africa in the beginning of that decade.

Malick Sidibé was 24 years old at the time. He was ready to capture the euphoria of his generation and pride of the young nation. Born in a rural district 300 kilometres from the capital, at a time when the nomadic roots of his Fulani tribe were already weakening, Sidibé was educated in institutions intended for the white colonists, where his talent for drawing and the graphic arts was discovered. When he was 20, he was referred to what is now the National Institute of Arts in the capital. As well as being the best student, he qualified as a jewellery designer, but he remained unsatisfied – by tradition, the Fulani are not dedicated to the arts, but to breeding animals. Everything changed when he was sent by the college to decorate the studio of the most renowned photographer in the colonial community: the Frenchman Gérard Guillat-Guignard, better known as Gégé la pellicule [Gégé the film]. Malick ended up being hired as the studio’s handyman.

While Gégé covered the major events in the colony, Sidibé learned the craft by osmosis. He managed to buy for a dollar a Brownie, the hugely popular camera Kodak had launched in the U.S. market half a century before, with an 8-frame film roll. At that time, with the exception of Gégé, the European photographers in Bamako did not allow their African staff to purchase cameras. The young apprentice was therefore a local rarity. He began his career photographing friends when he was invited to their weddings, birthdays and parties.

Turbans and Miniskirts

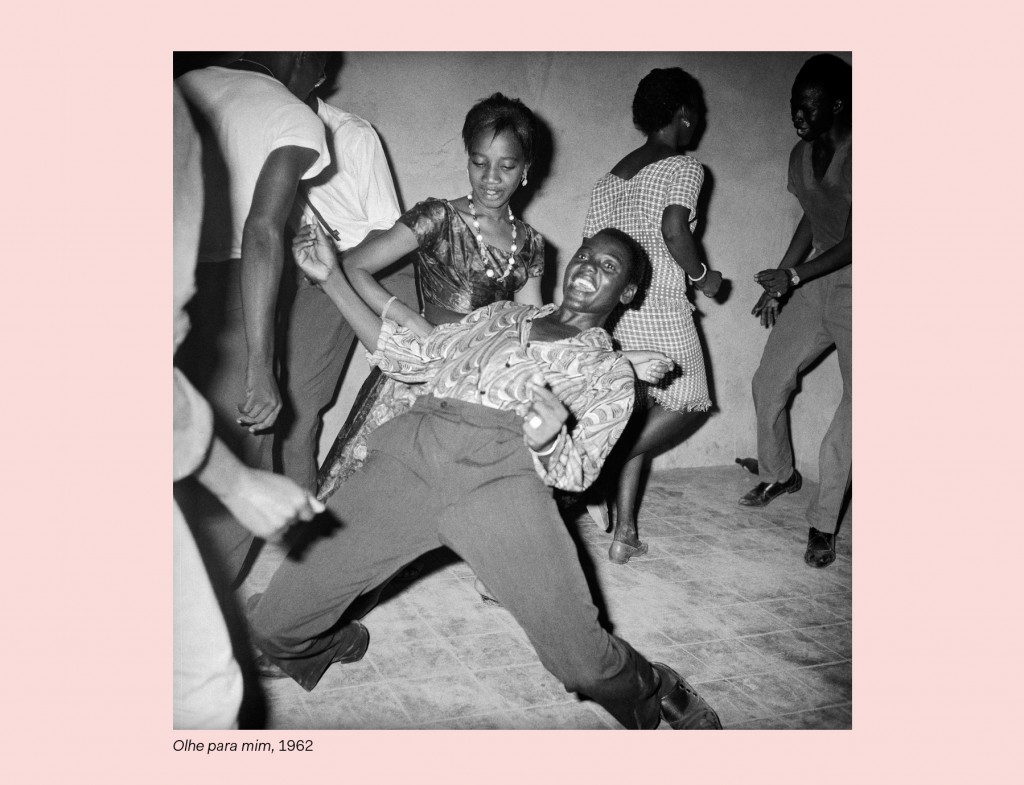

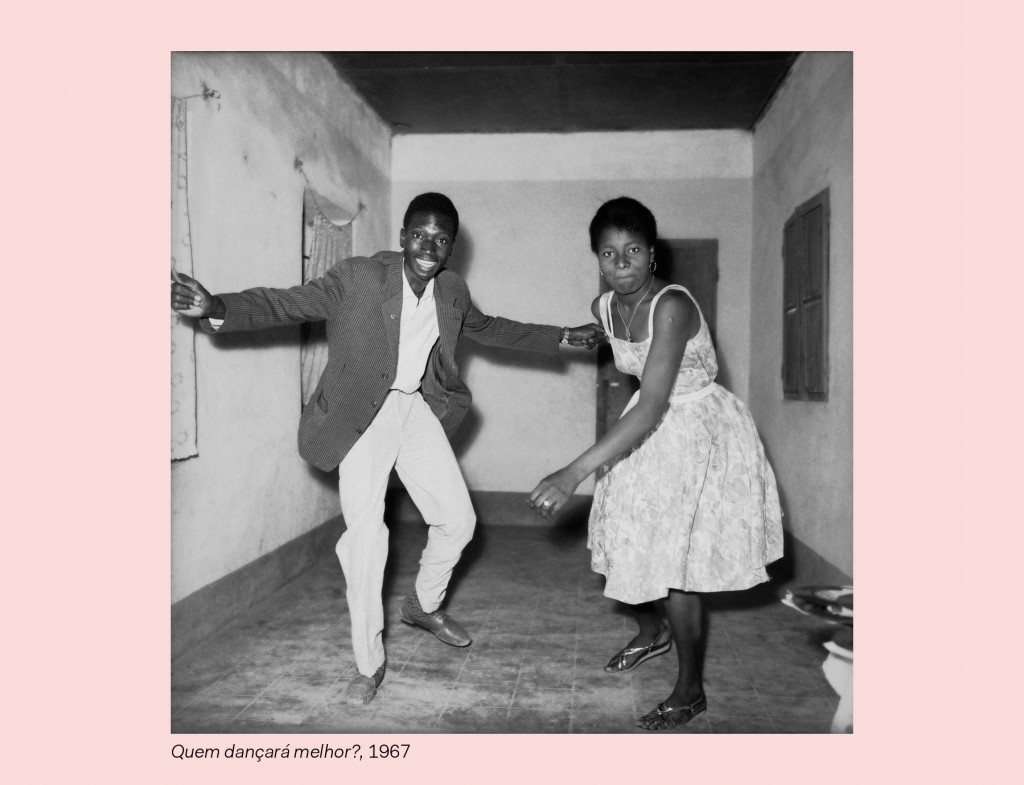

The unmistakable style, technique, look and visual language of Sidibé’s work only began to take shape in the ferment of decolonization, when the Malian nation discovered its eagerness to escape the cocoon and display itself. In the beginning, he became the visual chronicler of the generation of urban youth in the capital. He photographed day and night, developed the films late at night and the next morning fixed the contact sheets on the walls outside the studio, becoming an inextricable component of the changes going on around them. He was in tune with what he photographed. The discos and clubs of the capital, which until independence forbade the entry of native Malians, upped their rhythm.

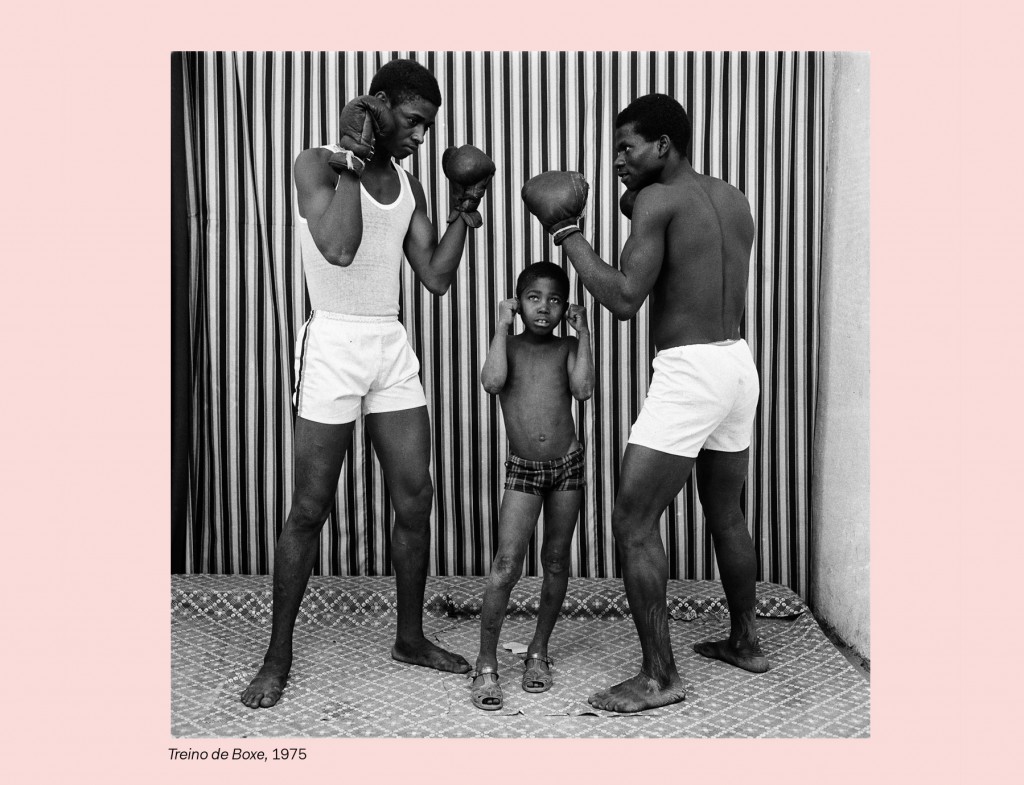

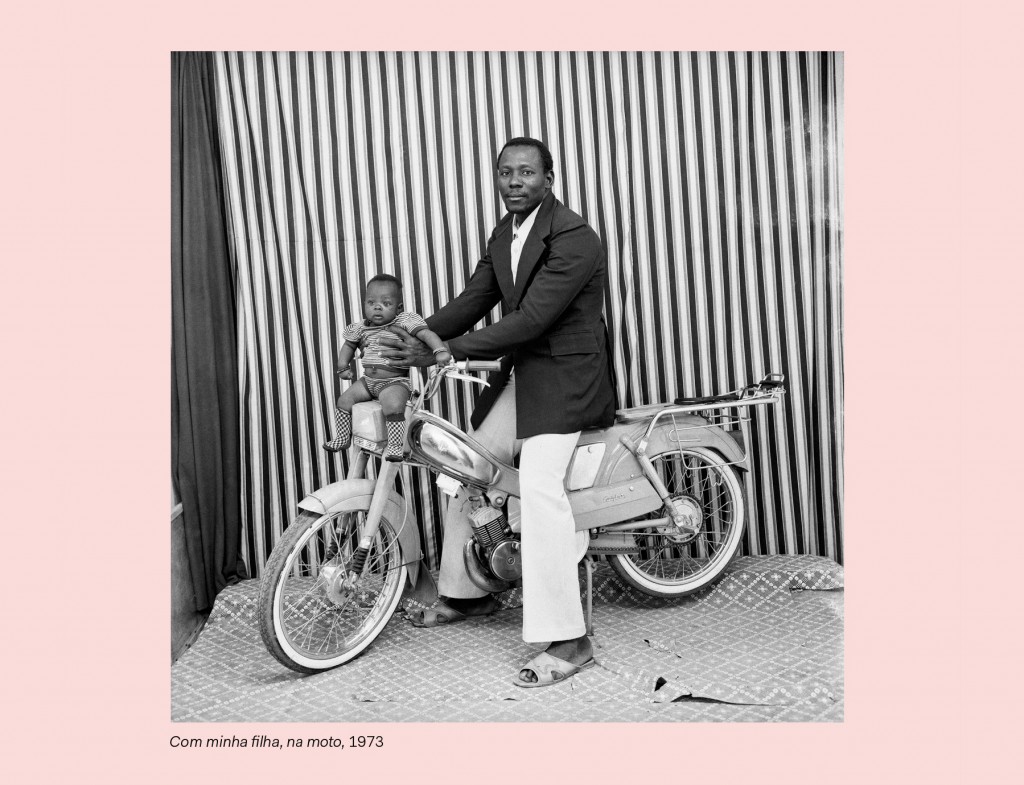

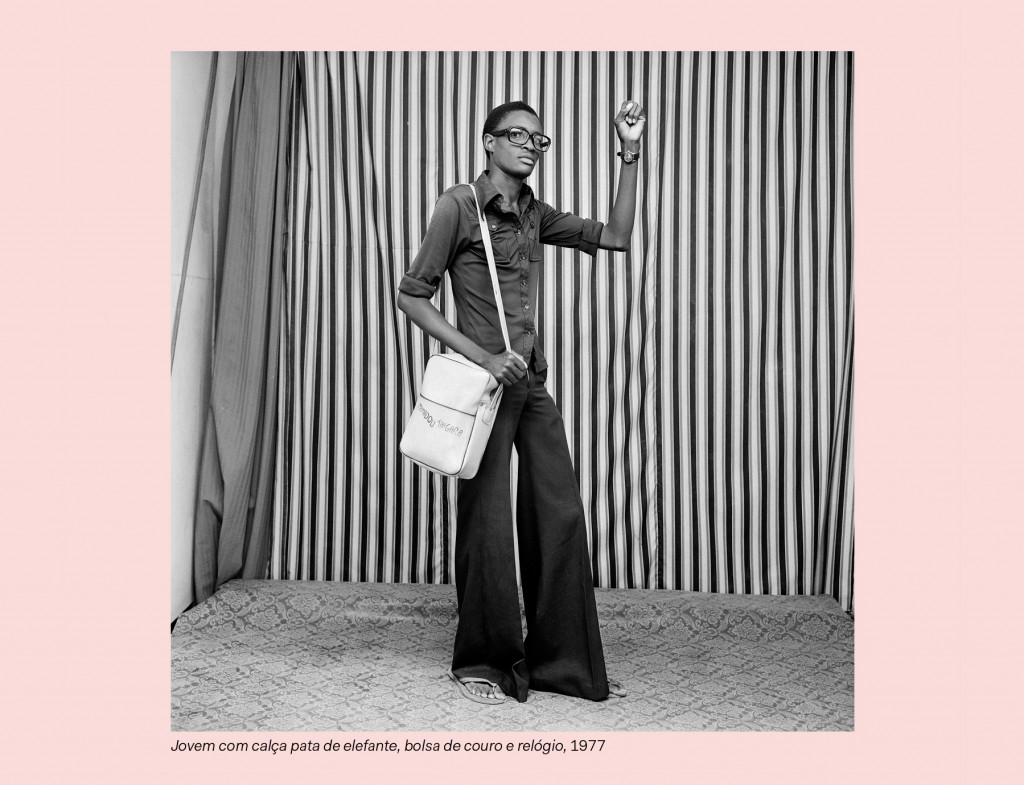

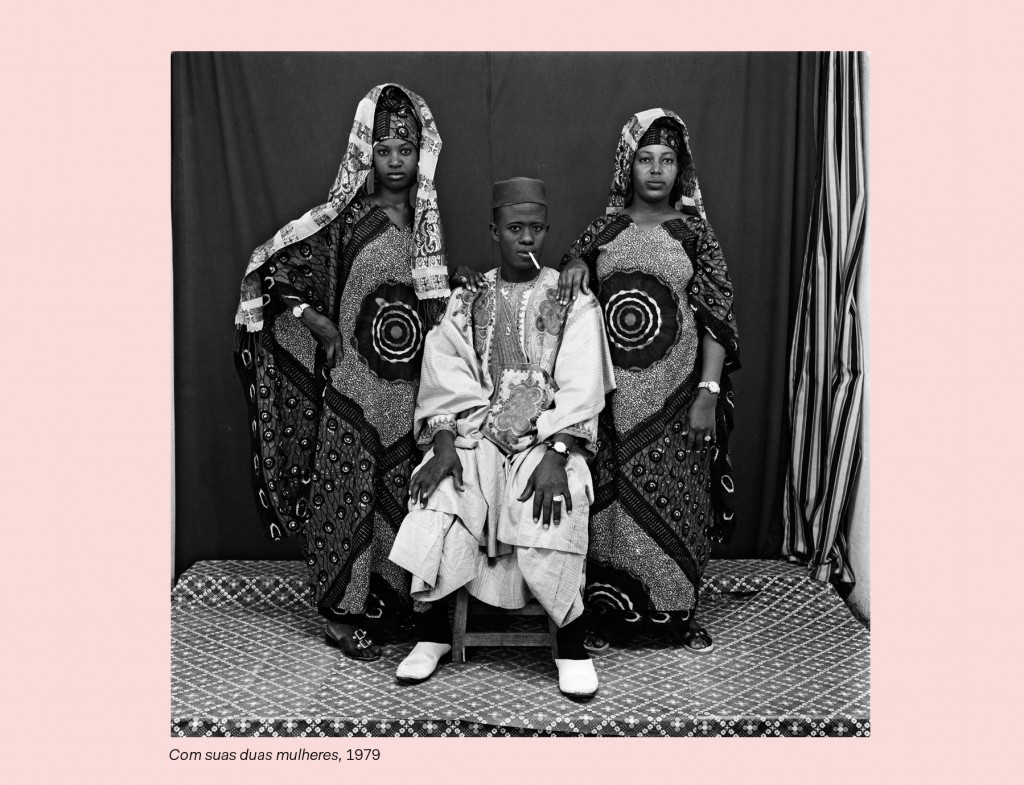

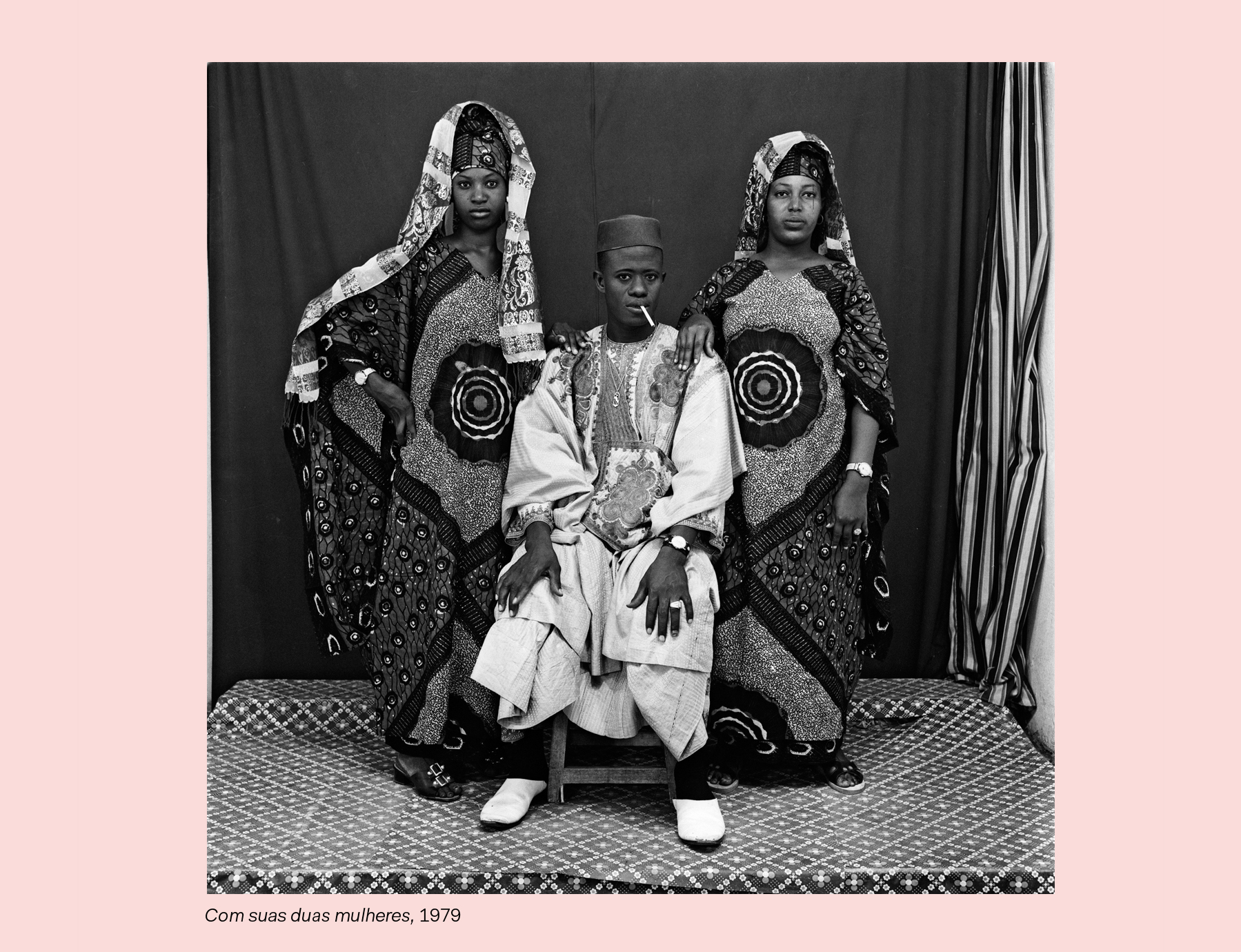

The joyous flowering of youth culture resulted in a wonderful mixed-up fusion of styles. Turbans, miniskirts and bell-bottom trousers made with African patterns lived side by side in the same wardrobe. It was the 1960s, and Western culture was embraced by the newly decolonized. First, through music, rhythms, style. Later, through the infiltration of the West’s consumer products.

Sidibé’s main work began to take shape in 1962, when he opened his own studio in a busy street in Bagadadji, the most popular neighbourhood in the capital – the name is a tribute to Arab merchants from Baghdad who settled there in 1922. The Malick Studio still functions in the same street, at No. 508, Door 632 – and Sidibé still does the honours, after more than half a century. At the age of 77 and with 17 children, he continues to meet the constant flow of European or African visitors to his simple studio with great good humour. It is not a coincidence that Sidibé is worshipped as the guardian of national history: he has saved every negative taken of the tens of thousands of people he has portrayed, and has catalogued them by date, location and name.

While in Europe the large photography studios began to lose prestige from the 1960s onwards, replaced by a more portable and informal photographic culture, popular demand for a conventional portrait lasted on for many decades in post-colonial Africa.

Visual Narrator

For art historians, the progenitor of studio portraits on the continent was Seydou Keïta, also from Mali. Born in 1921, Keïta opened his studio near the Bamako train station in 1941, when electricity had yet to arrive in the region. For this reason, all his work was lit with natural light. Even with this restriction, he left a remarkable portrait of the African elite of the time – both the urban and the tribal.

Malick Sidibé, half a generation younger, was able to open his studio on Bagadadji Street to all types of light, social class, individual dreams and expectations. He captured it all in black and white. “Black and white photos are more concrete, closer to the truth than coloured ones: they reveal their theoretical origin more clearly. They capture the beauty of the conceptual world. But the closer the colour photograph is to reality, the less true it is,” maintains the artist. His limited work in colour of exterior scenes, rural landscapes and collective activities deserves little attention. It diverges from the main body of his work by not focusing on what Sidibé tried most to capture: the individual.

In a candid interview with Laura Incardona, journalist and author of Malick Sidibé: La vie en rose [life in pink], the Malian revealed his emotional ties to the work to which he has dedicated his life. “My father never saw his own image, except in a mirror or reflected in the water,” he said at the time. “I see photography as a way to live longer, well beyond our death. I believe in the power of the image, so I spend my life trying to extract that which is most beautiful from everyone I portray.”

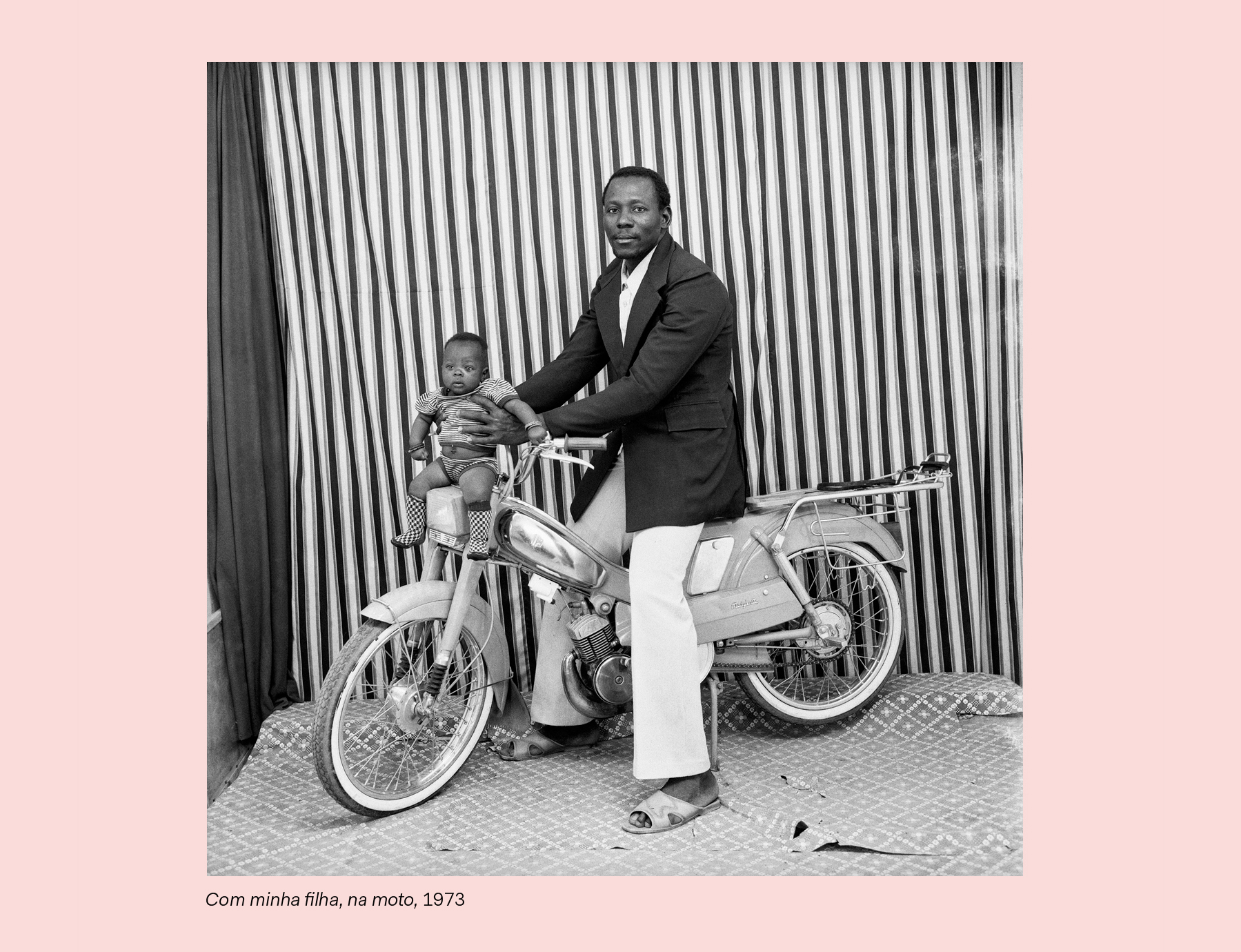

At the beginning, Studio Malick resembled more an extension of Bamako’s club and music scene. “It was a crazy, unique period,” recalled the photographer at the time of an exhibition of his work in London three years ago. “People would drop in, eat something and stay – and I would end up sleeping in the darkroom. They came to show their new hats, sunglasses, bell-bottom pants. They brought their scooters to be photographed and lived the fantasies of our generation. It was a make-believe studio, digesting Western influences.”

Gradually, however, the studio became a national magnet. Every Malian who wanted to have their picture taken by a blood brother would knock on the door. And Malick Sidibé, who has always considered himself a “visual storyteller” in the same lineage as his country’s oral historians, knew how to portray each one’s inner expectations. The result is impressive.

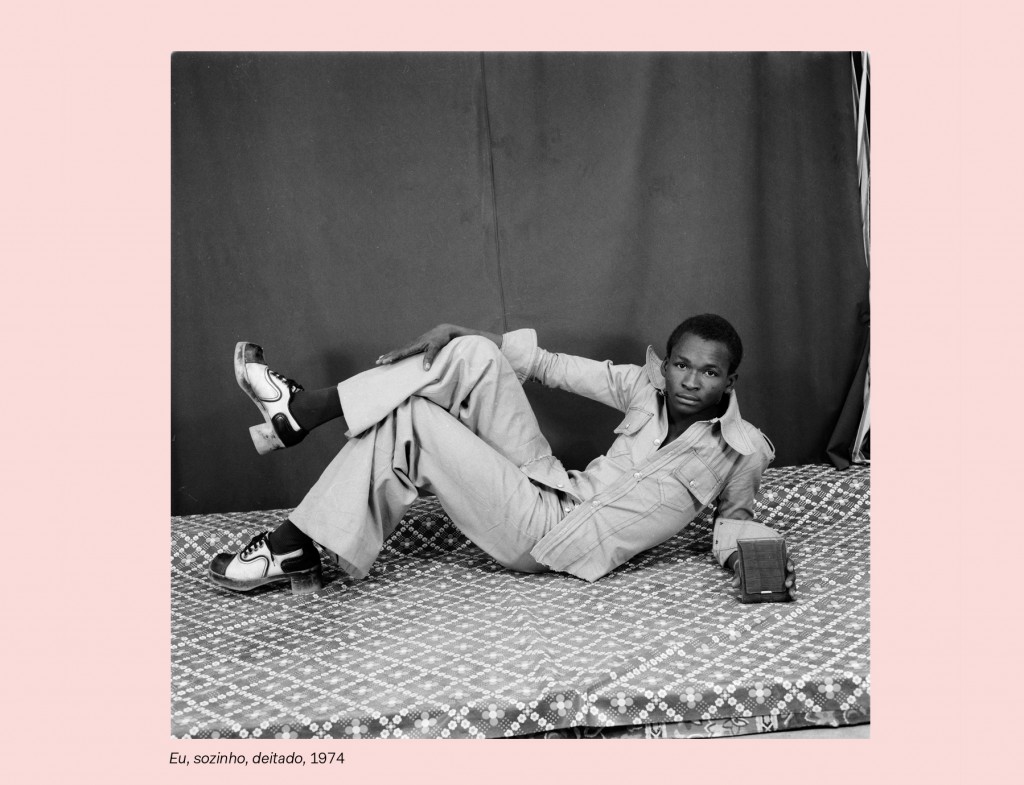

Each portrait is the result of a meticulous reconstruction of reality. And it is Sidibé who suggests the decisive gesture, who sets up the scene, who chooses the props and places them in the frame. His lens transforms ordinary people into personalities, and the studio session into a historic moment for the model.

Above all, in all the individual or group portraits, always artistically posed, what stands out are the faces. Their faces and their hands. This is surprising, as the background to most of the photos is full of stripes, squares, plaids or mosaics – strong patterns that should really overshadow or divert attention from the subject being portrayed. But Sidibé’s talent lies in achieving just the opposite effect: by saturating the space with shapes and lines he gives distinction to the one element that is not geometrical – the human face. The most important and lasting memory that the artist wishes to leave recorded on the image will always be of a unique and special person. Someone who illuminates the connections between past and present through one of the most fundamental forms of expression of African identity – the fabrics, with their endless variety of patterns, in perfect harmony with the body.

In other portraits, Sidibé opts for smoother, neutral backgrounds, free of any context, as if they were photos taken for identity documents. And, in a way, that is what they are: individuals, pairs, trios, small groups or larger groups – all asserting their identity and sense of belonging. The Hasselblad Foundation compares Sidibé with the master photographer who portrayed German society during the Weimar Republic: “Like August Sander, the great German photographer, Malick Sidibé has preserved the likeness of countless individuals, while in the process recording the face of the rapidly changing society they, as citizens, have collectively brought into being.” He was the portraitist of his city and his nation, and Mali’s most vibrant visual interpreter.

“God Smiles for Malick”

It was only in 1994, during the first edition of at that time classically-focused Bamako Photography Biennial, that the works of Sidibé and Seydou Keïta first received the attention of the Western critics and journalists invited to the event. Their enchantment seems to have been general, and was followed by an inexorable race to exhibit their work on the international circuit. For Sidibé, it was the start of a new life of travel, conferences and awards, in which he always participated with bonhomie, simplicity and wisdom. In 2003, he received the Hasselblad Award. In 2009, he became the first African to be awarded the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennial.

After these events, Sidibé has always tried to return to his own land and resume his observation post on Bagadadji Street. He began to teach photography and art in Bamako schools. As Madame Fanta, one of his wives, says: “God smiles for Malick.”

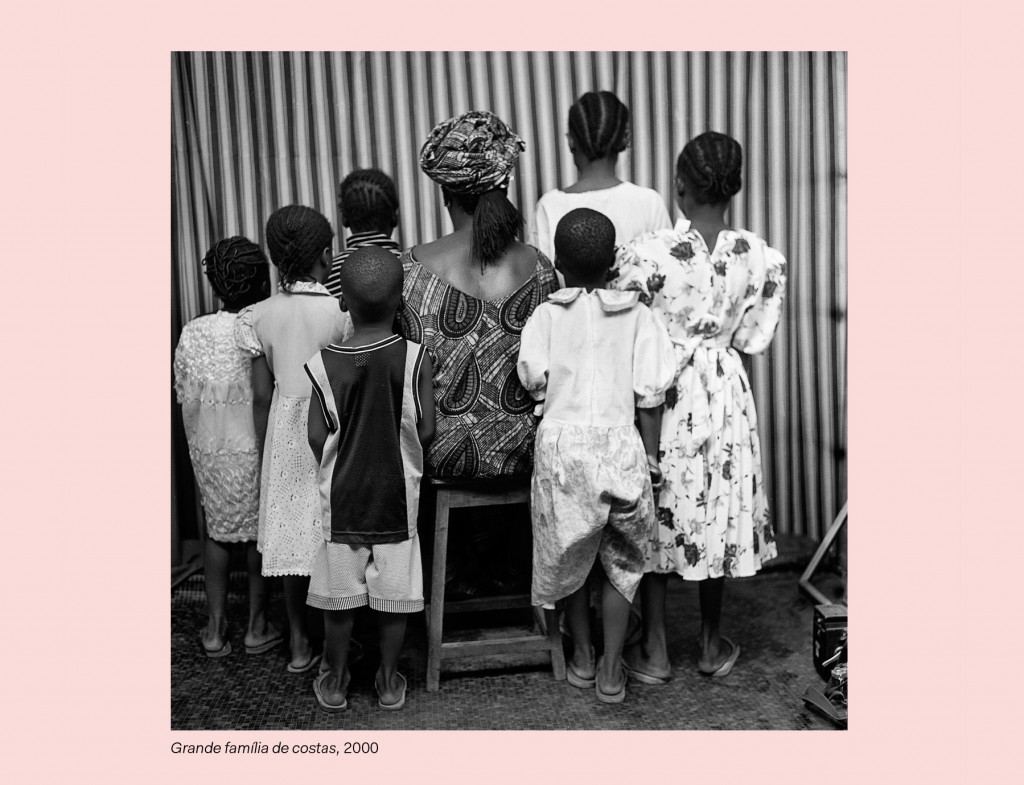

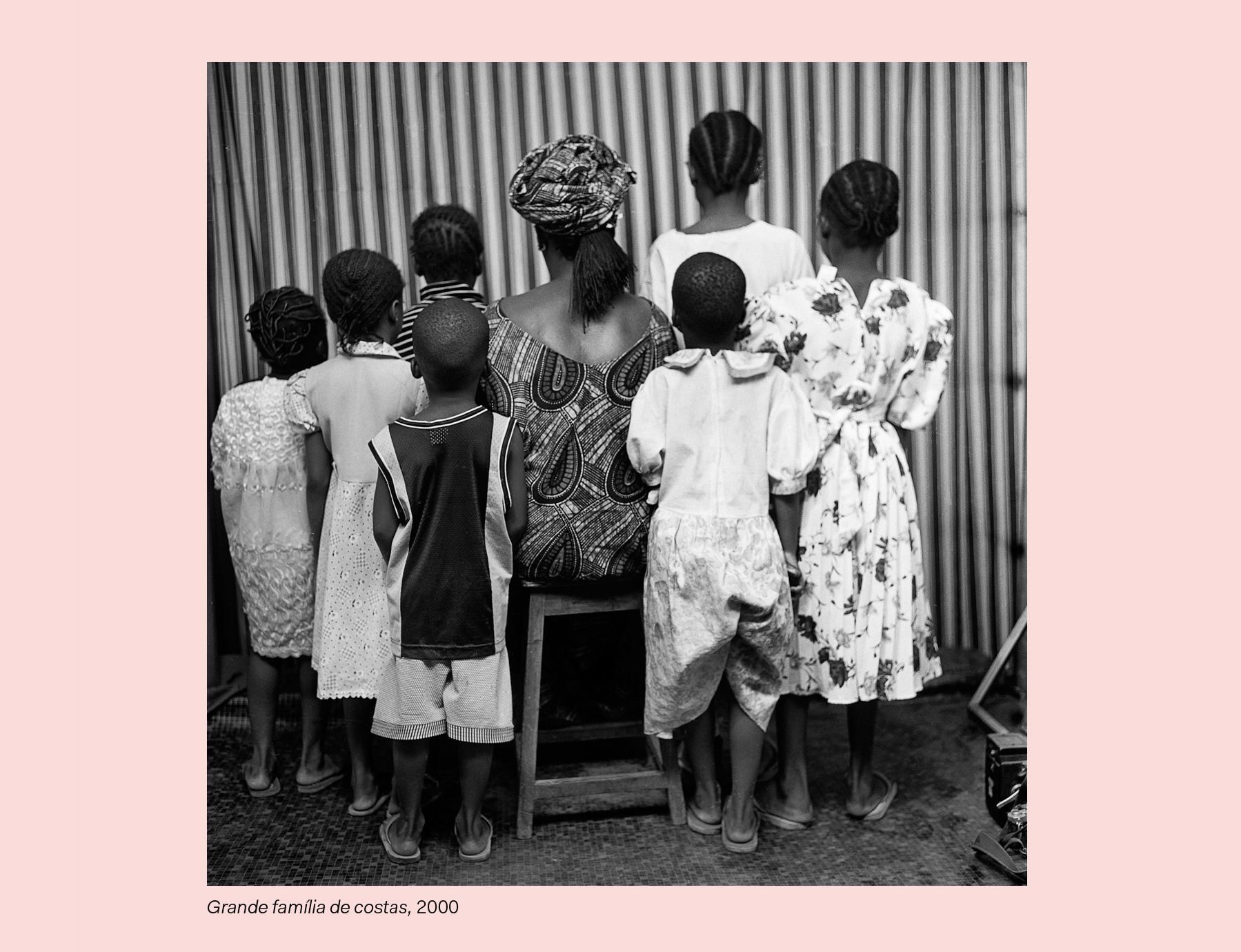

Much later in his career, already in the 2000s, the photographer began a curious series titled Back View, where all the protagonists, in groups or alone, are portrayed with their backs to the photographer. The effect disorientates the viewer, and Sidibé’s intention seems to be exactly that. According to Rowland Abiodun, Professor of History of Art and Black Studies, the series was taken essentially for a Western audience. A visual, social and personal antithesis to how European photographers from colonial times portrayed and saw Africans. Through Sidibé’s artifice, the foreign viewer loses the ability to understand something, limiting this knowledge to the portrayed and the photographer himself, both of them Africans.

Deep down, the dichotomy between native and alien is still present in Mali. The latest chapter in its long history began in January 2012, when Tuareg rebels and Islamist radicals, affiliated with al-Qaeda, took control of the northern half of the country. They declared an independent state, which they named Azawad, and imposed absolute obedience to sharia law on the population, banning music and television from public life. Hundreds of thousands of Malians started to flee, and Western countries were alerted to the possibility of a terrorist government establishing itself in the heart of Africa.

And because of this fateful fall of the cards, half a century after the euphoria of national liberation portrayed by Sidibé, Mali received French troops anew – this time, with open arms, as a decisive force to help stop the Islamic advance in its tracks. It worked out more or less well. With the backing of the UN and without reviving the old colonial temptations too much, the secession was contained, the French returned to their barracks and Mali held free elections last August. The elected President, Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta, returned to confronting his old enemy – corruption. And Sidibé had to leave Bagadadji Street.

Winner of prizes worldwide, as revered on his home soil as Jorge Amado or Oscar Niemeyer are in Brazil, Malick Sidibé has moved into the new millennium without giving a moment’s thought to digital photography. The last major commission that he accepted was in 2009, when the New York Times Sunday Magazine produced a special issue on the new fashion collections of the year, all inspired by African themes.

Sidibé accepted, proposed the now historic Studio Malick for the location and put some of his family of 80 to be his models. When the magazine’s production team descended on Bagadadji Street with their exotic collections from Prada, Christian Lacroix, Louis Vuitton and the like, the photographer felt at home. The journalist Andreas Kokkino, veteran fashion reporter, recalled the scene: “Instead of the usual hundreds and hundreds of frames per shot that I had become accustomed to in this era of digital photography, Sidibé took only two or three frames for every shot. When the shoot was over, he had shot only 22 frames on his Rolleiflex!”

But he won the 2009 World Press Photo award for the work. ///

images: © Malick Sidibé, courtesy Galeria Magnin-a, Paris

Dorrit Harazim (1943) is a journalist and former columnist for ZUM’s website.

Malick Sidibé (1936) was born in Soloba, Mali. He received the Hasselblad Award in 2003 and the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement at the Venice Biennial in 2007.

+ See a behind the scenes album from Studio Malick here.

///

Get to know ZUM’s issues | See other highlights from ZUM #6 | Buy this issue