Photojournalism in Crisis

Publicado em: 11 de June de 2014In conversation with ZUM about his latest book, critic and professor FRED RITCHIN addresses the dilemmas facing contemporary photojournalism, the role of the photographer and the challenges posed by digital media. Ritchin suggests that journalists find new ways to narrate events visually and confesses his enthusiasm for citizen journalism, even with the dangers it brings of the reporter being too closely connected to a story and of the lack of editorial control.

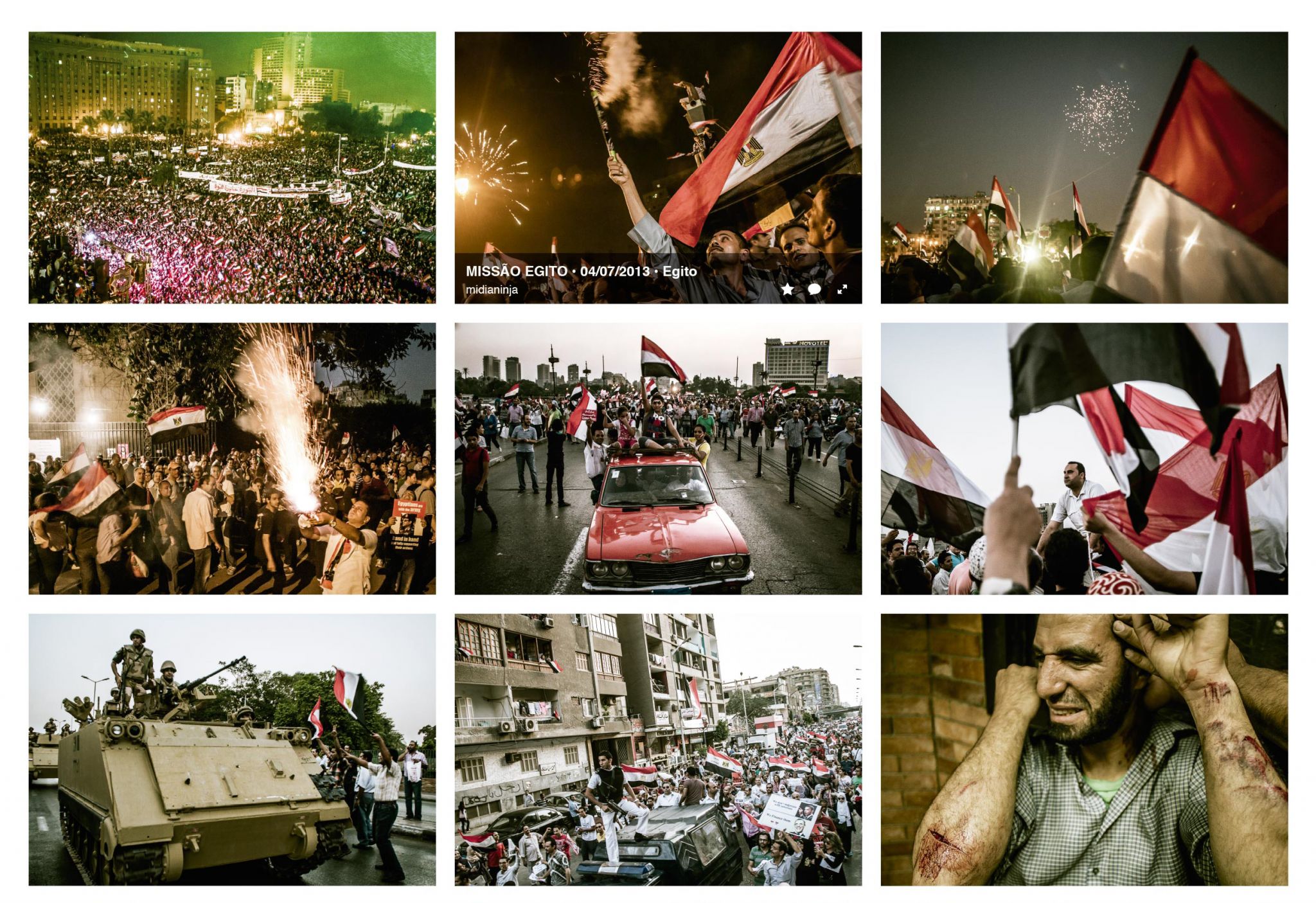

The press collective Mídia Ninja (where Ninja stands for Narrativas Independentes, Jornalismo e Ação – Independent Narratives, Journalism and Action) was founded in 2011. It became well known when the young members of the collective used their cameras, mobile phones and computers to record the spontaneous demonstrations that broke out throughout the country in June 2013.

PROFESSOR OF Photography at New York University, where he is co-responsible for the Photography and Human Rights Program, Fred Ritchin points to May 2, 2011 as the day when photography definitively lost what remained of its credibility. After a pursuit lasting nearly 10 years, the U.S. government announced it had killed Osama bin Laden, leader of Al-Qaeda, responsible for the terrorist attacks of September 11. In conversations with his staff and military advisors, President Barack Obama came to the conclusion that it was not necessary to publish a picture of Bin Laden’s corpse as proof of the assassination. Ritchin says that there were two fundamental reasons for this decision: “First, to prevent the worldwide anger that the image of a man shot in the head might awaken. The second had to do with a lack of trust: many people would not believe that the official photograph was genuine.”

This loss of credibility in photography has been Ritchin’s concern for three decades and is one of the issues that run through Bending the Frame: Photojournalism, Documentary, and the Citizen. Former photo editor of the New York Times Magazine, Ritchin had already pointed out that the manipulation of photographs was becoming easier, in an article published in the newspaper in 1984, six years before the commercial release of Photoshop. “I was afraid of the day when, while looking at images on the problems of poor countries, for example, the rest of the world would not necessarily assume they were true, for they can all be manipulated.” If this was done, pictures such as those the British photographer Don McCullin took of the famine victims in Biafra, would not have had the same impact. The images of skeletal bodies captured in the 1960s shocked the world and inspired the founding of Médecins Sans Frontières the following decade. “We learned what it really meant to be starving. The photographer had that power in those days.”

“Before, people thought over an important event because it was photographed – the Vietnam War, for example. Today, they do not give such things so much attention because the content of an image cannot be automatically trusted.” This insensitivity of the general public was starkly demonstrated in January, when some of the 55,000 images, taken as an administrative record by the Syrian government and smuggled to Qatar by a police photographer, were posted on the internet. “Although they showed 11,000 people who had been tortured and executed, the international community did not react strongly to the images of these corpses. The death of ordinary people in such a way should be shocking and lead to urgent action, because the civil war in Syria threatens the lives of millions of people.”

In the face of such indifference, new technologies can be a source of hope. “We live at a moment when reinvention and experimentation flourish. But photographers fear that no one will pay them if they experiment too much.” Ritchin demonstrates this by showing a photomontage on his computer screen. Two juxtaposed images show Kiev’s Independence Square, before and after the recent clashes between Ukrainian protesters and the police, which transformed this public space into an apocalyptic scene and led to the fall of President Viktor Yanukovych. “What you can do by manipulating these images is fantastic. On one side, the square appears as it normally does. On the other, the square is destroyed and burned. How did it get from one to the other?,” he asks. Then Ritchin opens the New York Times website and searches for photos of the Ukrainian conflict. “They are strong, but it is as if we had seen them before, because they use the same language. It seems they were waiting for an event to reenact it. Therefore, I question whether they are really able to generate a strong reaction in people.”

The collective has a flexible online organizational structure, which nowadays employs approximately twenty photographers. They are responsible for first deciding which events should be covered, then shooting them and editing the shots. Around 1,000 freelance photographers, who work in Brazil as well as in other parts of the world, eventually contribute with the collective as well.

Predictable Spectacle

Photojournalism – especially war photography, which is considered its most prestigious branch – has turned into a “predictable spectacle.” “Images seem to look the same and, as a result, don’t need to be examined that closely. Viewers resist them because they are so stylized.” A Peruvian and a Chinese peasant are likely to be shown in pretty much the same way. To meet the viewer’s expectations, they must symbolise resilience and oppression.

The mainstream press and influential awards induce professionals to use a traditional and repetitive language “scorned by many, as they seem to be rather a manifestation of corporate propaganda than that of understanding.” The photographer goes into the field to find and fit an image to a preconceived idea, which is in tune with the editorial line of the publication – and not to discover what is actually waiting out there. Subjects are more or less the same: a hungry child, the attractive woman, the brutal dictator.

Ritchin believes that the power to suggest and strengthen the standards of photojournalistic language, these awards prefer to reward clichés.” In 2009, Stephen Mayes, then Secretary of the World Press Photo, admitted that 90% of the photographs submitted seemed to be concerned with only 10% of the world. According to Mayes, there is little desire to break out of the sameness. “Images that could provoke a different view tend to be crowded out by those that are clearly exotic and perceive the problems of the world as a remote phenomenon about which others should worry,” says Ritchin.

In February this year, the American John Stanmeyer won the top prize at the World Press Photo. His picture Signal, taken for the National Geographic magazine and widely reproduced on the internet, shows African migrants gathering in the evening on a beach in Djibouti. They are holding their cell phones above their heads in search of a signal from Somalia, the neighbouring country. For them, this is an important stop on the way to Europe or the Middle East, and their cell phones are one of the few ways they have of contacting the relatives they have left behind.

Ritchin finds another symbolic meaning in this scene. “It’s an image about African migration, but it is also a reference to the shifting paradigms of photojournalism. The light from the screens of the four cell phones waiving in the air is symbolic of the need for a new connection, not only for photojournalists, but also for users of digital technologies and social media.” Stanmeyer’s photo is in line with a trend of journalism, whose goals are getting closer and closer to those of advertising. “The image is not intended to present a view of the world, but to make it look the same as ours, to represent it as we wish to see it.”

According to Ritchin, The Final Embrace, another shortlisted work for an award at the World Press Photo, did not get the top prize because it “shows pain.” Taken on April 25, 2013, Taslima Akhter’s photograph portrays the last embrace of a couple buried in the collapse of a garment factory in Rana Plaza, Bangladesh. “These photographs are very different from each other. One is about death and is tragic. The other speaks of our dream to connect. And which of the two did the World Press Photo choose for the most important award? The second, because it addresses our aspirations, and not our reality.”

Increasingly, the rule seems to be to reshoot the old classics or even recreate the idealised vision of the cinema. According to Ritchin, most war photography, for example, is driven by good and evil. Visual vocabulary is exhausted. “Photographers need to emphasize the role of interpretation in place of transcription.” Otherwise, they will be the protagonists of their own irrelevance. awards, such as the Pulitzer Prize and the World Press Photo, rarely go to experimental works. “Although they have

VI National Congress of the MST [no land movement], Mídia Ninja

Mídia Ninja uses social networks to publish the news. Their stories are followed on Facebook by around 250,000 people. In Flickr, the collective feeds a bank of images, which is divided in different theme albums, as the ones shown on these pages. These images can be downloaded in high definition and used in accordance with Creative Commons copyright licences.

The New Photojournalism

Ritchin says it no longer makes sense to think that the work of a photojournalist is to illustrate, prove something or support what written reports say. “For decades, we were brainwashed with the view that the job of a photojournalist is necessarily objective, has to do with facts and not interpretation. And even today there is little critical discussion of this notion in courses and at universities. But young people who access Facebook daily with its countless photos of their friends know that images are not objective.”

To Ritchin, it is time for photojournalists to move beyond the tradition that Robert Capa established in the first half of the 20th century. Capa adopted a “pragmatic” attitude and gave the following recommendation to fellow Frenchman Henri Cartier-Bresson: ”Don’t get stuck with the label ‘the little surrealist photographer’, make sure you are called a photojournalist.” Before founding Magnum with Capa, David “Chim” Seymour and George Rodger in the 1940s, Cartier-Bresson harboured the desire to be a painter and was involved with avant-garde artists.

In L’imaginaire d’après nature [the imaginary according to nature], Cartier-Bresson explained that the camera helped him to create a personal diary about the world. Photography was his attempt to understand reality. In a 1957 interview, he criticized the common way photojournalists worked: acting as if they were accountants, dividing everything into quantifiable elements. “Life is not made up of stories cut into slices, like an apple pie. There is no standard approach to a story. We have to evoke a situation, find a truth.”

Ritchin sees Cartier-Bresson as a good reference for future professionals, because he did not attempt to hide the subjective element of his work. The French photographer, according to Ritchin, belongs to a lineage that would sometimes treat their own credibility as a photographer ironically. This was a technique adopted, in their different styles, by Richard Avedon, Raymond Depardon, Gilles Peress and others. It was that perspective that underlay Richard Avedon’s project The Family. Published in 1976 in the Rolling Stone magazine, the project brought together 69 black and white portraits of the political and journalistic elite of the United States. The subjects are posed with “no attempt at neutrality or flattery.”

Inspired by the New Journalism of the 1960s and 1970s (a movement known in Brazil as Literary Journalism), Ritchin proposes that a similar approach in photography should be called New Photojournalism: “The most important legacy of the New Journalism to the challenges we are facing now may be the enthusiasm for experimentation in the face of a limiting paradigm.” Tom Wolfe, who coined the expression New Journalism in 1972, explained that the stimulus for this new genre came from the “discovery that it was possible to use in journalism, in a short text, literary devices such as ‘dialogism’ and ‘stream of consciousness’ to stimulate the reader intellectually and emotionally.”

Writing in this style, Wolfe, Gay Talese, Norman Mailer, Truman Capote and others ran the risk of sounding self-centred and being inaccurate by inserting their own impressions into their journalistic texts. However, their frank involvement in the reporting did add a layer of understanding that would, perhaps, have been impossible if they had stuck to the journalistic principle of impartiality. According to journalist and author Dan Wakefield, their open admission of subjectivity was “the opposite to the usual pretence of standard journalism.”

Ritchin defends the idea that a photograph should have as sceptical a view as a text. As with words, images “lie, but are also capable of telling the truth, though not the whole truth.” Anyone who looks at something is responsible for judging whether it is worthy of interest and for identifying different points of view. As for the question of image manipulation, Ritchin suggests the viewer be alerted whenever it is used: “Manipulating an image can be fun, but in journalism you need to tell the reader about it.”

Ritchin mentions Mídia Ninja as an example of a less predictable or official coverage of events, explaining that they are close to what or who is being photographed, have different points of view, and produce an abundance of images, as the current digital technologies allow.

The Useful Photographer

One of Ritchin’s most pressing concerns is with the continuing importance of photojournalists. A 2009 survey by the European Federation of Journalists concluded that there are three serious obstacles facing the profession: low pay, copyright, and competition from amateurs. For Ritchin, social engagement is necessary for the photographer to remain an asset. Once we are unsure of its authenticity, the photograph bluntly becomes a way to intervene in reality. It is for the professional to ask themselves if their efforts are going to help maintain the status quo or throw a critical light on the powers-that-be.

Ritchin does not rely only on traditional media outlets. He sees New Photojournalism being actively pursued on the internet by amateurs. Their images of the Iraq War (2003- 2011) and the Arab Spring (2010) had the most impact. The first photos to reveal the torture in Abu Ghraib or confirm the existence of chemical weapons in Syria were not shot by photojournalists. “The ones that bring us essential information about a contemporary event are taken or distributed by a legion of digital device owners.”

In principle, anyone who has direct experience of an event should know more about it. “If you want to have a better understanding of the recent protests in Brazil or Ukraine, it is best to talk directly with someone who lives in these countries,” says Ritchin. In the digital age, information tends to gain a conversational tone, replacing the traditional, hierarchical and elitist news system, which is determined to give the final ruling on a piece of news. “The diverse experimentation which is to be found in the billions of images now freely available – from the strident advocacy of citizen journalism to photos detailing an individual’s mundane everyday activities – must be seen as building a vital pool of social documentation.”

The social media stimulates dialogue between the creator of an image and its observers. Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and Instagram, for example, have expanded the role of citizen journalism, a term that now includes everything from “the revolutionaries of the Arab Spring to neighbours concerned with the problems of their city block.” “The open subjectivity of these amateurs, their explicit involvement and the lack of financial incentives can help them reach an audience that is in sympathy with the motives of these ordinary citizens, which may be similar to their own,” says Ritchin. “These images are, to some extent, a shared dialect, created by sharing images via mobile phones and capable of capturing many more details.”

Despite his enthusiasm for citizen journalists, Ritchin admits that there are limits to their skills. “Citizen journalism runs the risk of falling into activism. And this position of ‘defending a cause’ makes viewers or readers increasingly sceptical. During the Arab Spring, for example, amateurs may intentionally limit themselves to showing police violence against demonstrators, and fail to show the opposite, even when it occurs. Still, it is easier to understand the interests of a citizen journalist than it is to understand the point of view of traditional media.” In Brazil, Ritchin sees the work of the collective Mídia Ninja as less predictable and official, with their coverage of the social protests taking a different form to that of the mainstream media.

To Ritchin, amateurs need curators. “A challenge facing us now is to understand what kind of people could be the organizers or filters of this material. How can we make these new editors’ point of view as transparent as possible and ensure that their prestige is equal to that of the authors of images?” Ritchin calls these new curators “meta- photographers”. They can be either a college student or respected professional, but both should be able to provide a context for the work of amateurs or citizen journalists.

Three decades ago, a member of the Magnum Agency, photographer Susan Meiselas, began a project with the Kurds – a nomadic ethnic group inhabiting parts of Iran, Iraq, Syria, Armenia, and Turkey. After photographing the Kurdish refugees persecuted by Saddam Hussein in the late 1980s, Meiselas asked the survivors to create their own collective history by contributing with personal photographs and helping to identify the individuals portrayed in them. Under the title akaKurdistan, the work resulted in a website, a book and an exhibition, and became an influential model for this type of project. Another example is the transparent curatorial approach in the Basetrack project, by Teru Kuwayama and Balazs Gardi. From 2010 to 2011, US marines in Afghanistan were asked to report their experience in the war and communicate with friends and family, using photos and texts.

As the founder of PixelPress, a project which promotes human rights and studies new forms of digital storytelling, Ritchin says that, with this technology, people, whose point of view used to be ignored, now have access to a channel where they can express themselves. “The problem is that in order to get to know these different perspectives, we have to make a massive and continuous effort. We can’t just be passive, although we are conditioned to consumerism and to expect that everything should be immediate.”

According to Ritchin, there is a widespread feeling of helplessness nowadays. “People think they have no influence on reality.” This impression can trigger a vicious cycle. “If they choose to ignore what’s happening in the world because it is more comfortable, they will not pay attention to photographic work. And this lack of focus results in less resistance to power.”

If we want to understand the new reality, in which every two minutes the same number of images are taken as during the whole of the 19th century, Ritchin thinks it is necessary to invent new formats. Even the word “photography” seems dated to him. “When the automobile was invented, it was called ‘the horseless carriage’. Digital photography is an inaccurate term and is condemned to fall into disuse.”

According to Ritchin, the critical views of essayist Susan Sontag made sense in an analog world. Sontag wrote in 1977 that the camera fragmented reality, making it malleable and opaque, imploding the continuity between past and present. Digital technologies could transform the photograph into something less conducive to atomization. “It seems that we have created digital media to meet our political, spiritual and psychological needs,” claims Ritchin. He advocates the idea that humanity has realized that the survival of the species depends on our ability to lead a less egocentric, centred life. The digitization of knowledge supports the individual’s desire not be alone. ///

Fred Ritchin is a professor, curator and photography critic. He founded the Photojournalism and Documentary Photography Program at the International Center of Photography in New York, and his publications include After Photography (2008). He writes and edits the blog afterphotography.org.

Mídia Ninja is a press colective.

///

Get to know ZUM’s issues | See other highlights from ZUM #6 | Buy this issue