Beyond the exotic

Publicado em: 3 de July de 2018A traveller who hated travelling, Claude Lévi-Strauss begins Tristes tropiques (1955) by ironizing the importance that is usually given to banal passages in explorers’ stories. He follows this with acidic comments about the heat of boats, children and beetroots. The tuber is used as a metaphor to represent the massification of 20th century civilizations.

“Mankind installs itself in monoculture; it is preparing to produce mass civilization, like the beetroot. Its everyday meal will only include this dish.”

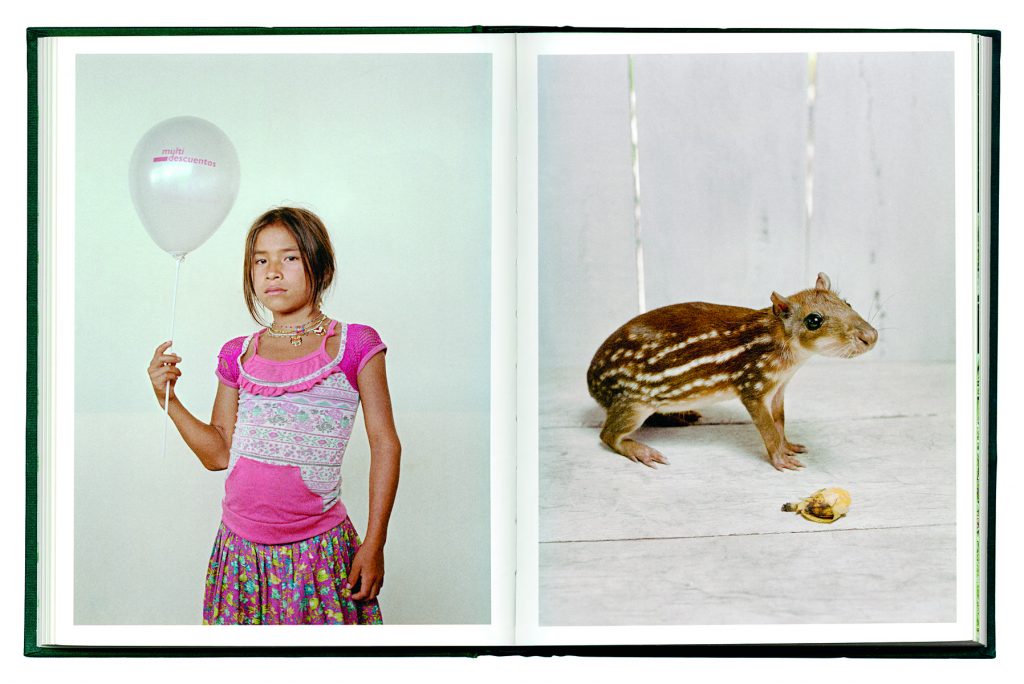

The Jungle Book: Contemporary Stories from the Amazon and its Fringe (2016), by the Swiss photographer Yann Gross, revisits and updates Lévi-Strauss’ thinking from more than six decades ago. As societies become closer, intensifying massification, they adapt according to their own specific natures. The green cloth book cover displays gold illustrations of a jaguar, an alligator, and an Indian kid with soccer-player Neymar’s haircut. The mix of wild animals with a boy who imitates the world-famous player’s looks sums up the view of the Amazon presented by Gross, a forest culture which is also connected to urban centers and the world of celebrities. Photographs succeed each other – of beauty pageant contestants, a chained wild dog, beer cans hiding cocaine, a shaman who became the doorman for an evangelical church, the quality control at a condom factory and a teacher called Hitler Capinoa Sandiego.

Just over a decade before he published The Jungle Book, Gross photographed the inhabitants of the Rhone valley in Switzerland who dreamed of the American way of life even without ever having visited the United States. Horizonville, as the essay was named, features western-style restaurants, strip clubs, trailers sporting Confederate flags, bikers and many people wear- ing cowboy hats. The title of the essay refers to a city that does not exist and was appropriated from a gas station sign that Gross encountered at the end his three-month road trip. Gas stations are symbols of American pop culture and are found in the work of artists like Edward Hopper and Ed Ruscha.

Between Switzerland and the Amazon, Gross lived for some months in Uganda, where he also became interested in cultural cross-over. In Kitintale, a suburb of Kampala, Gross came across the group responsible for building the country’s first skatepark. In the meager landscape, he recognized codes common to his own skater universe.

Many kilometers separate the Ugandan skaters from the surfers of the Amazon in the Brazilian state of Pará, who meet twice a year to surf the long pororoca tidal bore wave on the Capim River, one of the microstories he tells in his new book. The extent of the territory through which Gross traveled – beyond Brazil, he went to the Amazonian areas of Ecuador, Colombia, and Peru – allowed him to find a greater variety of situations and to deal more broadly with stereotypes and acculturation. It is the collision of contemporary elements with the visual imaginary of the Amazon that gives shape to the book.

Explorers’ accounts are a reference for those who study the Americas. Before they came, however, there were other ways of representing what was beyond the ocean, a land unknown in Europe. One such representation was the Portolan, an old form of nautical chart used to predict distances and directions between ports. Whether it was for the artistic, mystical or religious inclinations of its creators, or to praise the courage needed to embark on long and uncertain journeys, it was customary to include drawings of hideous animals and monstrous figures in the Portolans. The cover of Gross’ book shows an illustration reminiscent of these charts. With the coat of arms of the Tabula Regionis Amazonicae, the map marks the location of the characters and objects depicted in the book, in no less terrifying versions than the old drawings. The distances represented are also heterodox.

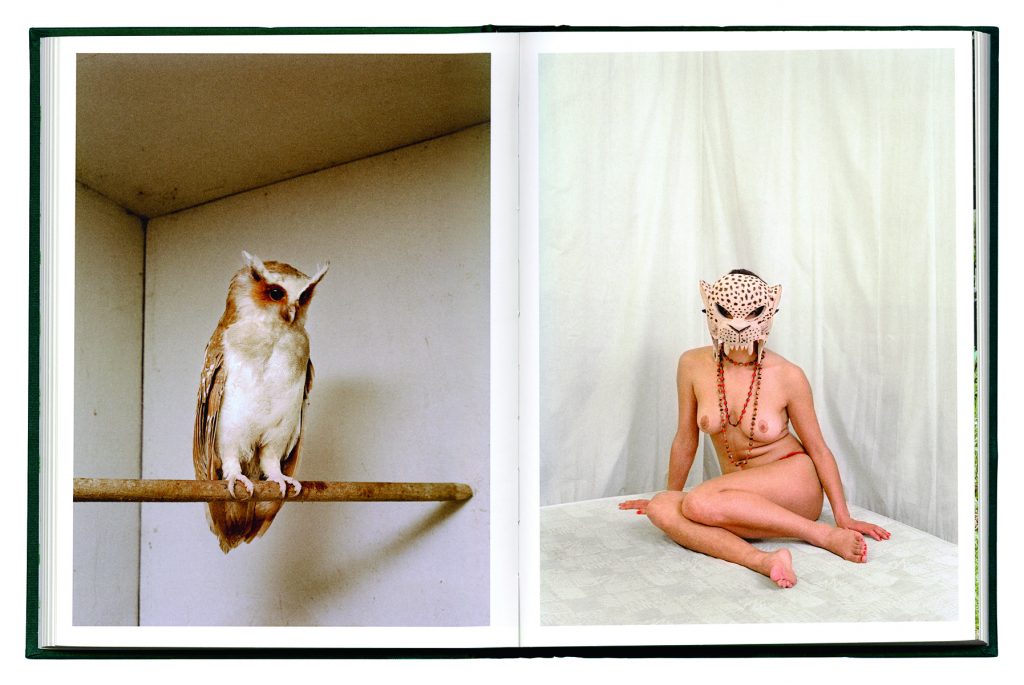

Legend has it that Spaniards led by the explorer Francisco de Orellana (1490-c. 1546) baptized the Amazon River after losing a battle to indigenous warriors who strongly reminded them of the women warriors of Greek mythology. In his photos, Gross also revived certain myths. The portrait of a naked, curvaceous girl with a jaguar mask refers to Tupichua, a beautiful jaguar-woman who, according to the French anthropologist Hélène Clastres, adorns herself with attractive painting and leads men to lose their mind. If we copulate with the jaguar-woman, she “starts to look painted and ceases to look like a woman, scratching the ground and roaring, like the victim.”

The relationship between men and animals also appears in a photograph of a boy with a turtle shell on his head. At the end of The Jungle Book, an index offers an explanation of the images: “After the meal, the turtle’s shell becomes a toy for the kids.” Seeing the photo, we can imagine either that the little ones had fun with the remains of the animal or believe that the boy actually wore the shell as an unusual hat. By emphasizing the exception in his dreaming images, Gross mixes fact with fiction.

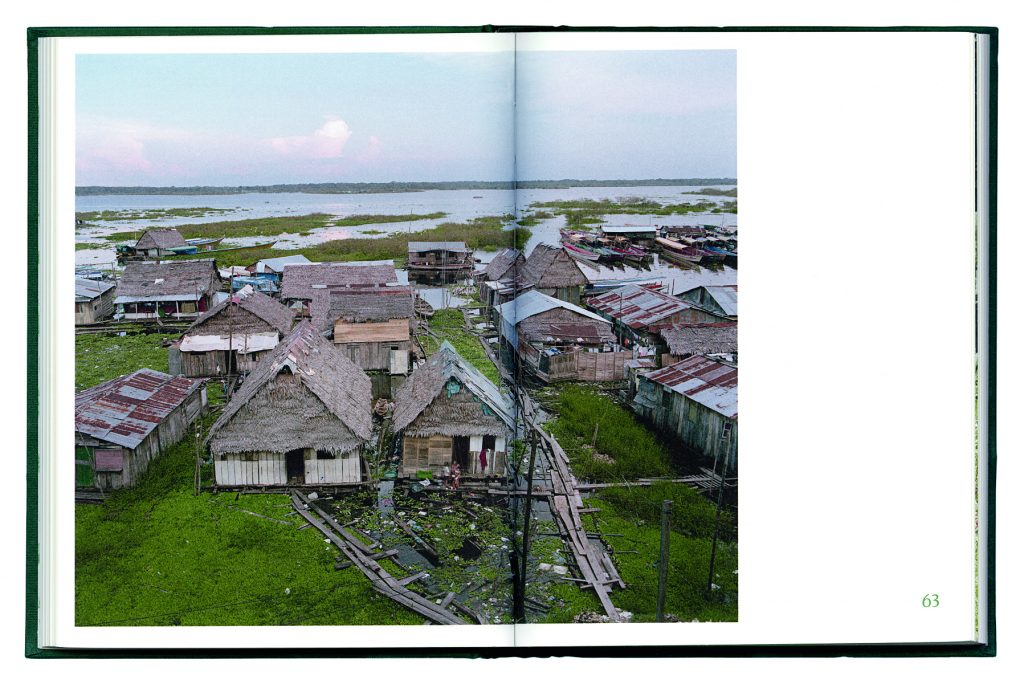

The jaguar-woman and the turtle boy were photographed in Iquitos, Peru. The expansion of the city absorbed the surrounding Indian villages, leading to the gradual disappearance of the traditions of each community. Many inhabitants do not know their origins or that of their ancestors and thus construct an identity that incorporates elements from other parts of the country, such as dances, clothes and popular music.

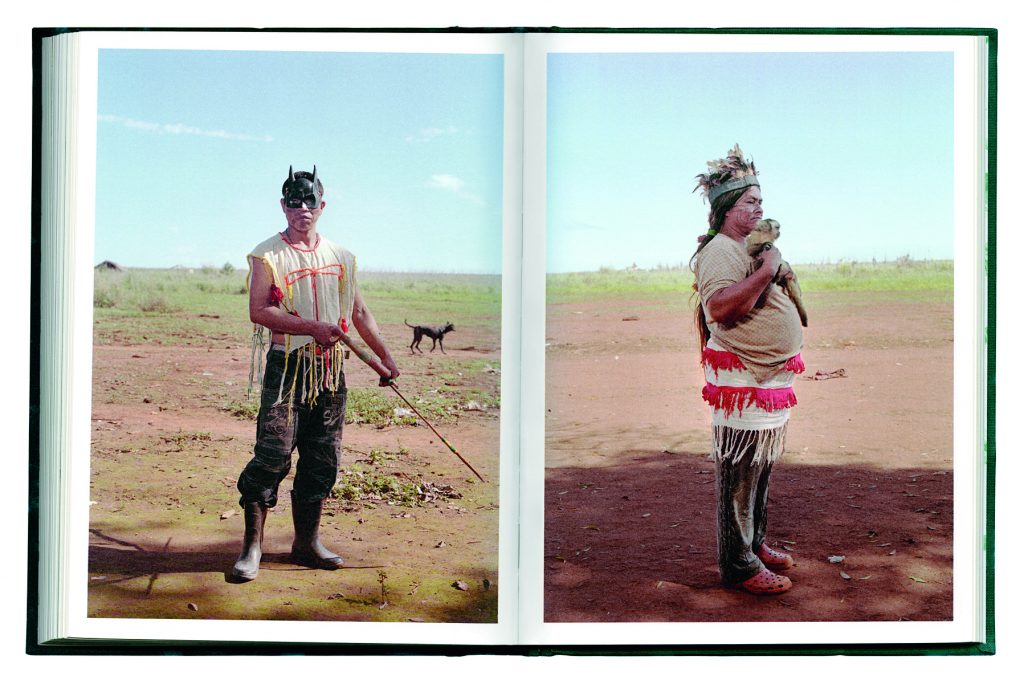

Nearby, in the Peruvian Santo Tomas, Gross found young people of Cocama origin trying to resume their old rituals. In some of his photographs, the Mashakaras of today (“masked men” in the Kukama- Kukamiria language) reinterpret an extinct Cocama ritual, with masks representing demons and fantastic creatures from the mythology of various tribes.

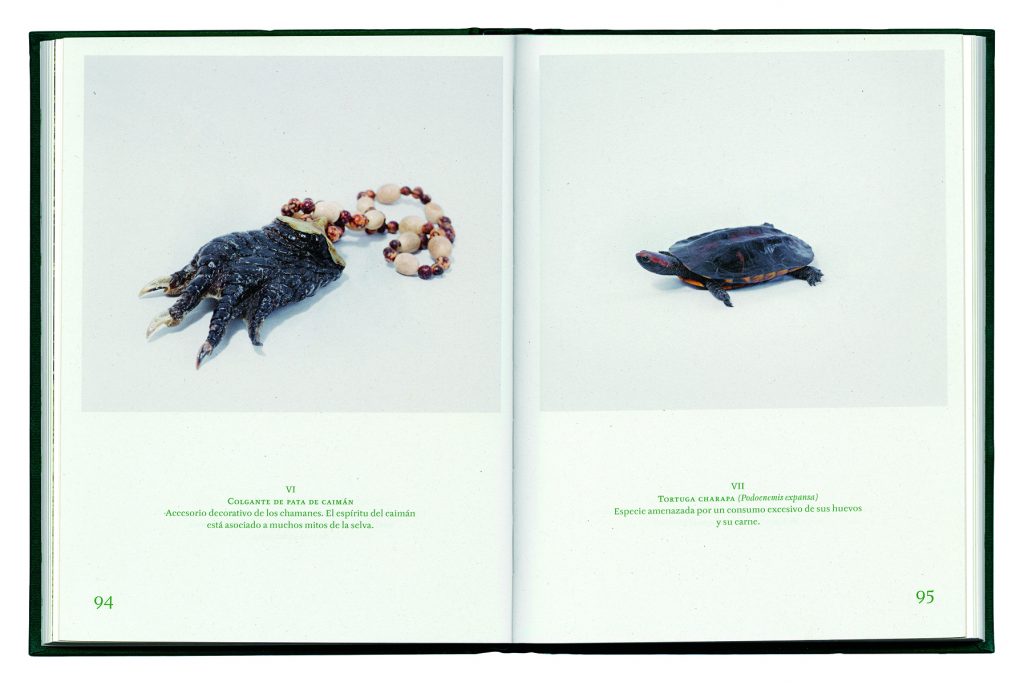

From the 18th century onwards, explorers dedicated themselves to the detailed drawing of the fauna and flora of the Amazon region, especially the work of the naturalist Alexander von Humboldt (1769- 1859), who traveled through the Spanish part of the continent and drew his subjects centered on a neutral background and isolated from the environment. In the center of The Jungle Book, Gross uses this approach in sixteen photographs of plants and animals, printed on thinner, matt paper. The sequence of photos, which seem to have been taken in the studio, starts with ayahuasca lianas and follows with lizards, aphrodisiac plants, finishing with an armadillo. The elements, captioned with their popular, scientific names and a brief explanation of their most common uses, were not found in the forest by the photographer, but purchased in the Belén market in the Peruvian Amazon.

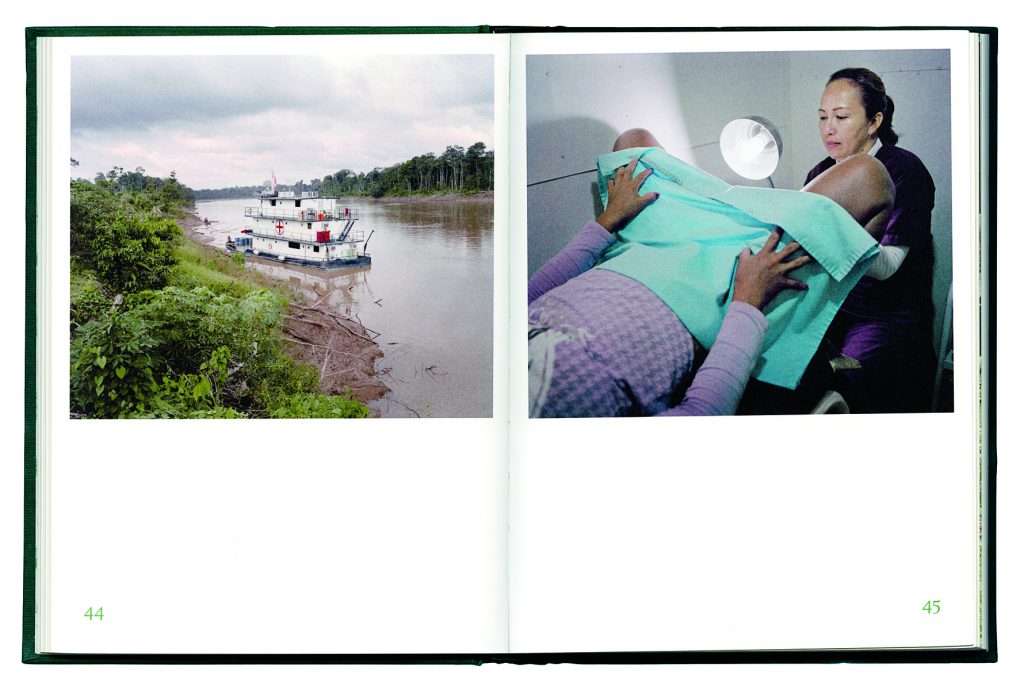

Humboldt also painted landscapes that offered a positive perspective of nature and its inhabitants, as opposed to the views that saw the tropics as unhealthy, inhabited by a degenerate population. The natural landscapes photographed by Gross are dazzling, but are often followed by images of predatory mining, buildings or an armed figure. Gross exalts the romantic vision of the forest while revealing its decay, through his photographs of boats and abandoned buildings, and his desaturated, melancholy color palette with opaque tones and little contrast. Gross is economical when posing his characters for the portraits. And his descriptions are more substantive than verbal: a man holds a guitar without playing it.

The word is also essential in the book, published in English by the American publisher Aperture, in Spanish by the Mexican RM and in French by Actes Sud. In addition to the explanatory comments at the end, short and objective texts accompany many of the photographs to identify characters or to reproduce testimonials. The style of communication is dry and often anecdotal, focusing only on the unusual. In one passage, Gross reports that upon arriving at an Indian settlement after sailing for two days on the Napo River, all that could be heard was “the resounding beat of electronic music.” The commentary accompanies a pictorial landscape, covered by mist, and shows how the reality of the Amazon frustrates romanticized expectations.

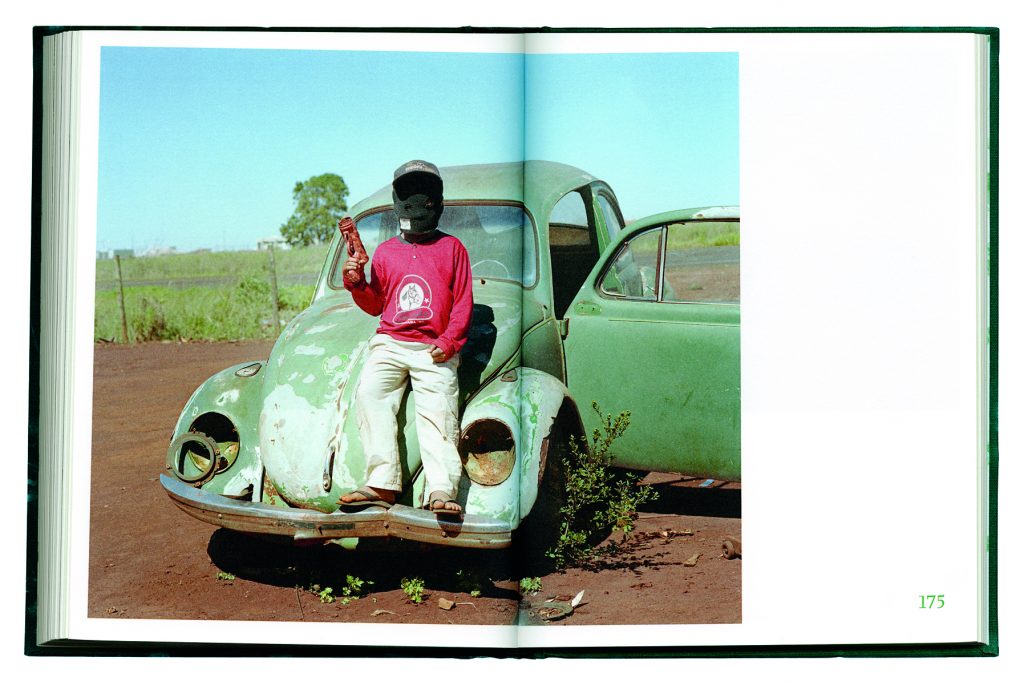

The title of the book refers to the literary classic written by the Anglo-Indian Rudyard Kipling, published in 1894. The Jungle Book is a collection of fables in which anthropomorphic animals venture in search of the moral education of their readers. Mogli, the most famous character, is a good, typically romantic, savage. In Gross’ work, however, there is no room for an idealized vision. While unmasking the stereotypes, he often finds new exotics: an indigenous hip-hop group, a Colombian Tarzan, an Indian chief with a teddy bear or the boy with Neymar’s hair.

The Jungle Book deals with modern identity, the notion of progress and development. It is a construction made from several overlapping images, which include stereotypes and exoticism. The idea of homogenous civilizations, centered on monoculture, is also questioned in the book. Depending on how you cook the beets, Gross believes, the taste may vary. ///

Yann Gross (1981), a Swiss photographer and filmmaker, is the author of Horizonville (2010), Kitintale (2010) and The Jungle Book (2016). He was awarded the PhotoEspaña descubrimientos Prize in 2008 and collaborates with publications such as National Geographic, Aperture and The New York Times Magazine.

Daigo Oliva is deputy editor of the Image Group of the Folha de S.Paulo newspaper.

Daigo Oliva thanks Ronald Raminelli (UFF), Karen Macknow Lisboa (USP), Rafael Marquese (USP), Wesley Kettle (UFPA) and Leonardo Marques (UFF).

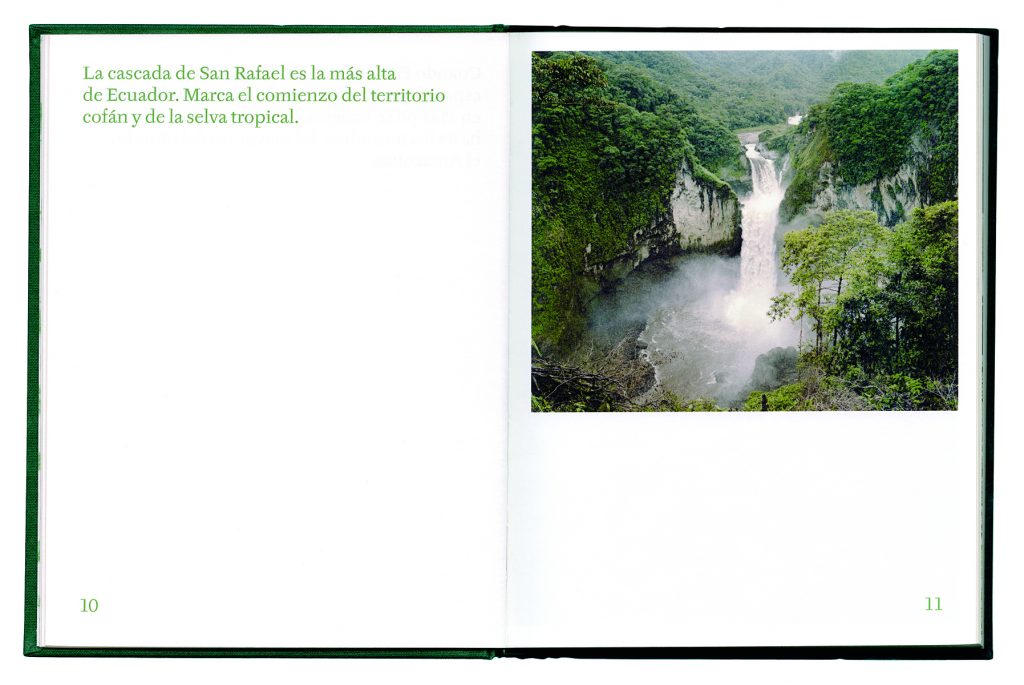

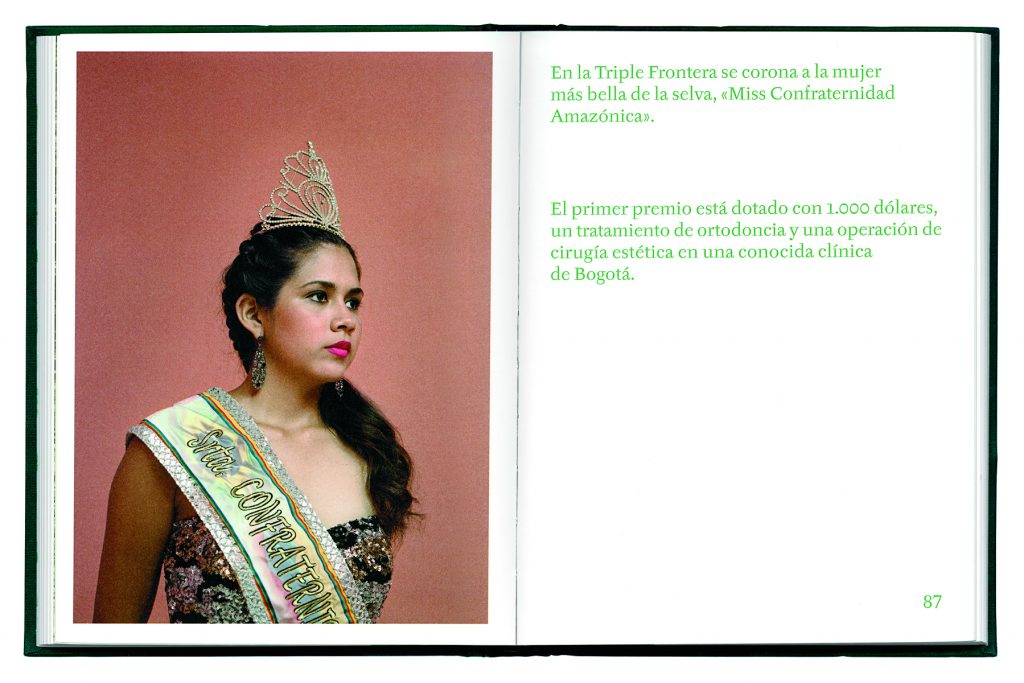

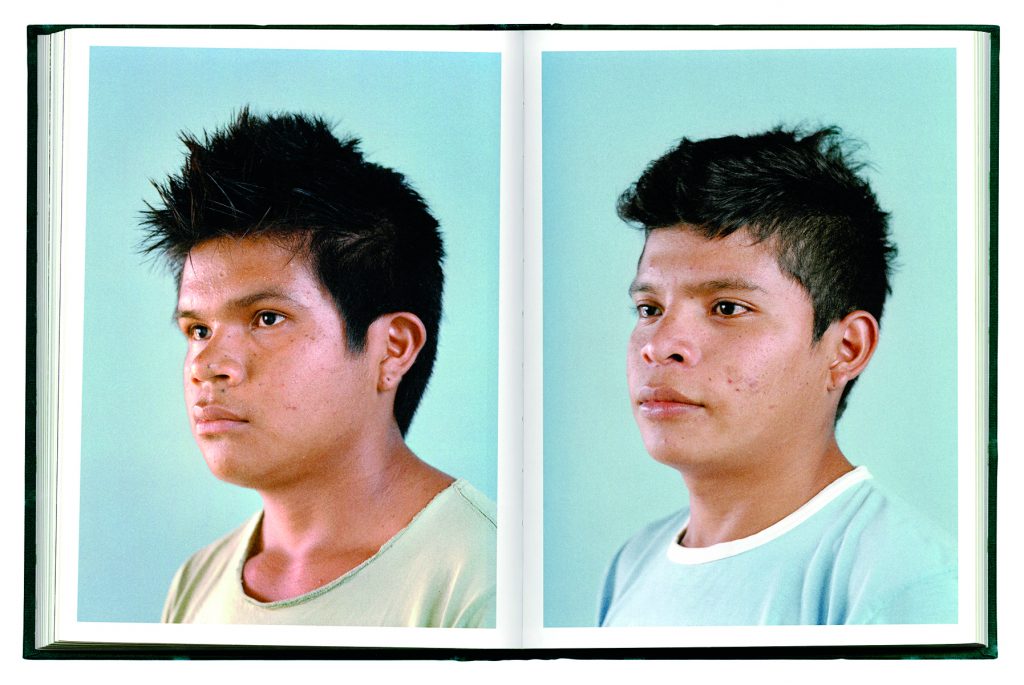

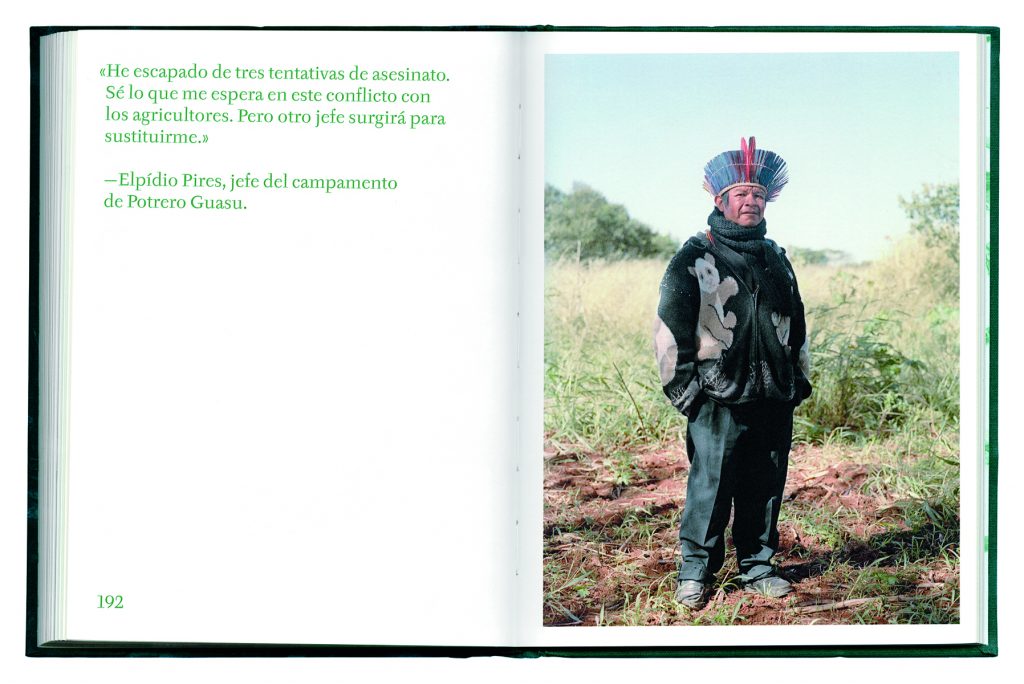

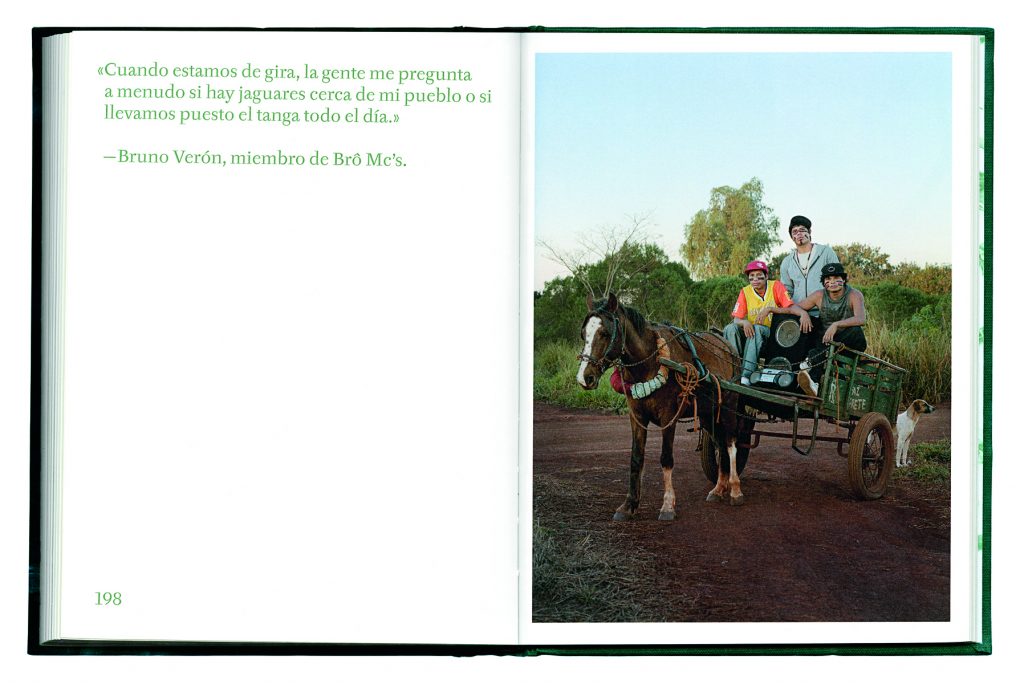

captions p. 153: The San Rafael waterfall, the highest in Ecuador, marks the beginning of Cofán territory and the tropical rainforest at the foot of the Andes. p. 161: At the Triple Frontier, the most beautiful woman from the jungle is crowned Miss Confraternity of the Amazon.The first prize includes an envelope with US$1,000, an orthodontic treatment, and cosmetic surgery at a reputable clinic in Bogotá. p. 162: VI – Pendant with caiman foot decorative accessory for shamans. The spirit of the caiman is associated with numerous forest myths. VII – Charapa turtle (Podocnemis expansa). A species threatened by the overconsumption of its eggs and meat. p166: “I have escaped three assassination attempts. I know what awaits me in this struggle with the farmers. But another leader will emerge to take my place.” – Elpídio Pires, cacique of the Potrero Guasu camp. p. 167: “On tour, people often ask me if there are jaguars near my village and if we wear thongs.” – Bruno Verón, member of the Brô MC’s.

Tags: daigo oliva, fotografia, o livro da selva, yann gross, ZUM, ZUM14