Where Did The Slave Quarters Go?

Publicado em: 11 de February de 2015

The new Brazilian edition of Gilberto Freyre’s classic book removed the slave quarters and the black slaves from its cover. Intrigued by the change, the history professor MAURICIO LISSOVSKY shows how the old slave quarters have lost their meaning of oppression and cruelty to become a place of enjoyment. The result of these shifts is that the slave quarters are returning, in other even more violent images. |

|

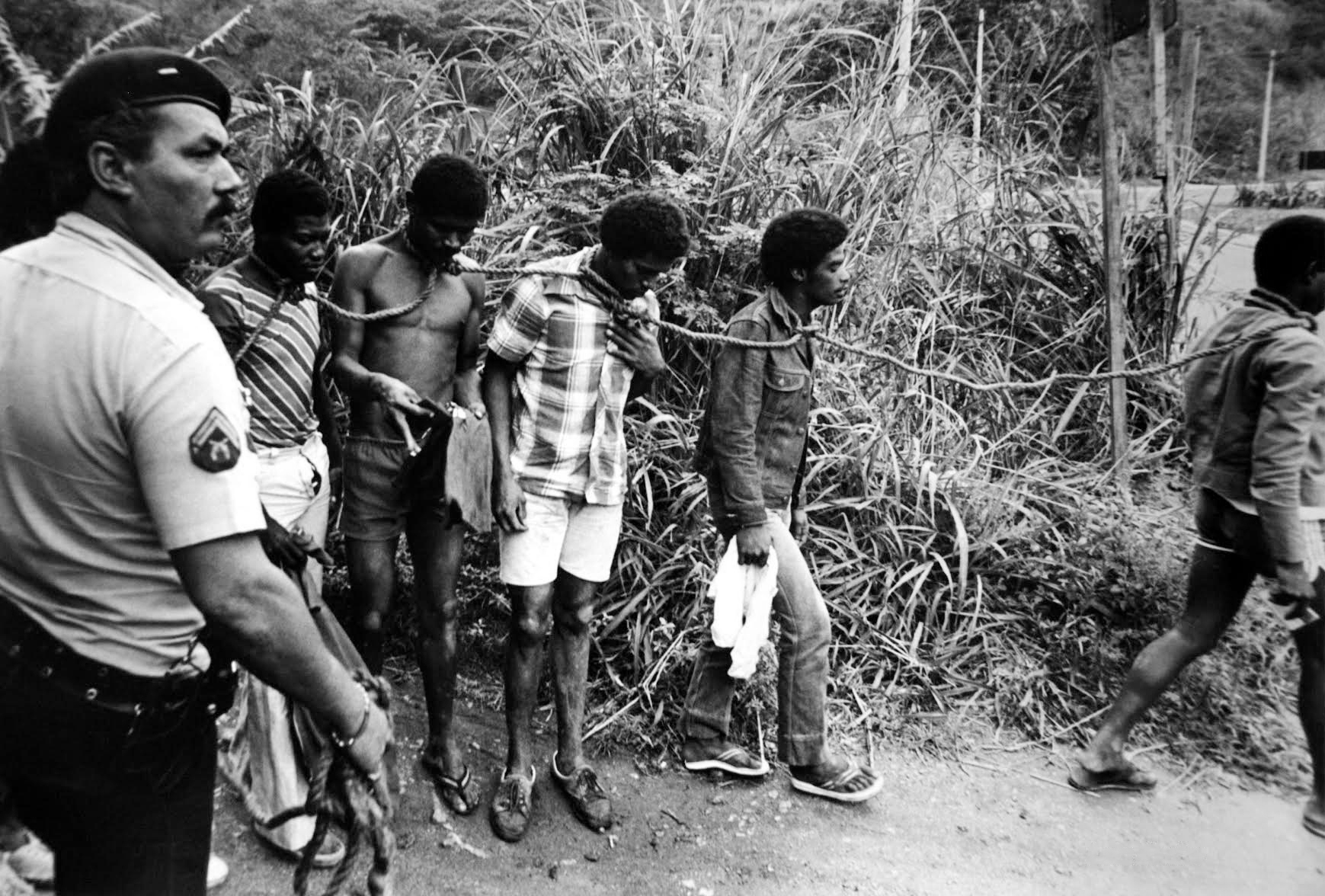

| Casa-grande & senzala [The masters & the slaves] (2013, Editora Global) | Young robbery suspect at Flamengo, Rio de Janeiro, 2014, Yvonne Bezerra de Mello |

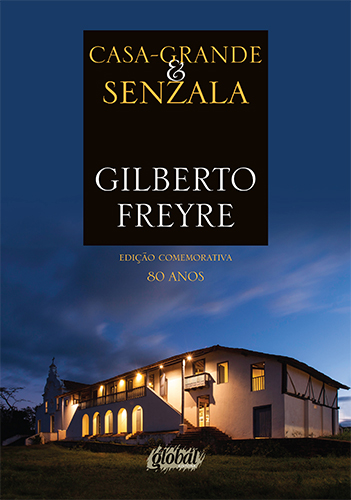

In December 2013, Gilberto Freyre’s classic book Casa-Grande & Senzala (The Masters & the Slaves) turned 80. The work has received numerous critiques and revisions in the decades after it was first published, but remains our most influential sociological essay and, above all, the most lasting of interpretations of Brazilian society. In Freyre’s view, the master’s house and the slave quarters form an essential duality, which is not only the foundation of private social relations amongst Brazilians but also of the country’s political culture. The two buildings, adjacent to each other, were simultaneously antagonistic and complementary, as with the masters and slaves that inhabited them.

As was to be expected, a beautiful commemorative edition was published to celebrate the event. On the cover, a picture of the master’s mansion under a twilight sky. It rises magnificent, glamorous, lit like a monument, ready to serve as a location for a film or a soap opera. But there is something disturbing about this picture. Where have the slave quarters gone or, indeed, the images of slaves which were used to illustrate dozens of previous editions? Why have the editors felt free to remove from the image one of the two structures that were so closely linked that Freire emphasized their relationship with the use of an ampersand? Who permitted it? How much of this photograph was actually authorized?

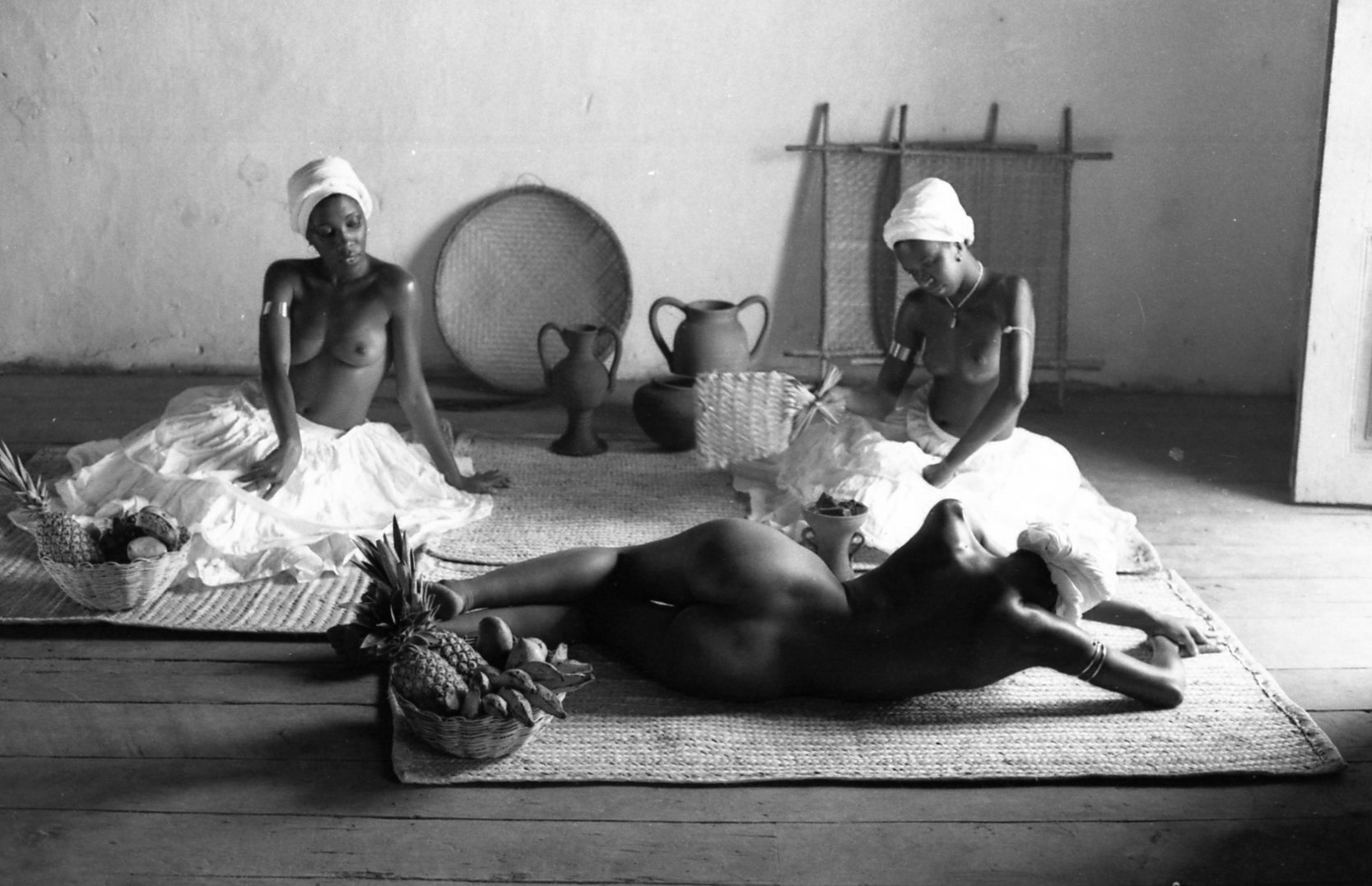

Seeking answers to these questions, I remembered seeing a catalogue of an exhibition held in 1982 in João Pessoa, supported by state and local governments and the Federal University of Paraíba. It was a work of historical fiction with staged photos as in a photonovel and was entitled Engenhos e Senzalas [mills and slave quarters]. Freire himself, then aged 82, wrote a preface to the catalogue in which he extolled the skill of the photographer, who with “romantic imagination charmingly enlivened by the most beautiful realism” masterfully depicted the “equivalents of misses and maids” and showed them in “totally nude but not pornographic poses.” This equally glamorous photographic version of Freyre’s book does not favour a particular skin tone in its depiction of nudity and eroticism. While dining, the priapic master cannot wait for the end of the meal to undress his wife. Meanwhile, the older son, the future master of the estate, encounters his favourite slave and enjoys her in his bedroom. The next day, it is the mistress of the house who has her maids bathe her as she prepares to meet her lover during her husband’s absence. And the husband, in turn, uses his supervision of the work of the captives as an excuse to visit his black mistress. In the spacious and well-lit slave quarters, conceived here as a harem, the slaves are already naked and he has a romantic encounter with the principle object of his desire.

Engenhos e senzalas [mills and slave quarters], 1982, photographic interpretation of Gilberto Freyre’s classic by Luiz A. Bronzeado

From samba to photonovel, the broad vision of this piece (“the struggles of life”) has faded away. Agrarian economy has succumbed to the desire economy. So, it is perfectly natural for the slave quarters to disappear from the book cover as well. But such a powerful phrase – the masters and the slaves – could not be diminished that easily. Having acquired new connotations, we encounter it again in circumstances which would have been unimaginable before. In the town of Arraial d’Ajuda on the coast of Bahia, for example, there is a guesthouse called Casa-Grande & Senzala. Would someone actually stay there? Certainly, but only in the big house – the master’s mansion. The hotel’s website has a photograph of one of the rooms. The chairs and the bed, with a canopy and lace mosquito net, are images of a traditional and luxurious space. But what about the slave quarters? A small engraving on the bedroom wall alludes to slavery, but shifts the reference by depicting a scene of servitude in ancient Egypt.

Now that all the guests are staying in the master’s house, where are the slave quarters in this tourist package? The answer is easy: in the restaurants. In 2012, in the historic city of Paraty, a Senzala Steakhouse opened. It was not the first nor will it be the last. A quick internet search reveals dozens of restaurants with the name Senzala throughout Brazil. The word’s significance has diminished to such an extent that no one really takes offence at being asked to eat in the slave quarters. On the contrary, the idea is accepted immediately, in the certainty that the best and most refined food will be on offer.

Every image is a symptom. The photograph on the cover of Freire’s book suggests that the imaginary vision of the master’s house has now come to inhabit the slave quarters. In Recife, Gilberto Freyre’s birthplace, the new significance of these terms has reached its most dramatic expression. In Apipucos, on the other side of the street from the imposing residence that was the sociologist’s home and is now a museum, a motel called Senzala has been opened. The publicity slogan did not waste the joke: “Visit the master’s house and have fun in the slave quarters.” Freyre’s heirs managed to embargo the publicity material, but the motel caught on and is a success. The billboards advertising the suites with sado-masoquistic themes read: “This is where you come for a whipping.” Like the restaurants, the Senzala motels have multiplied and spread. In Porto Alegre, there is a motel where references to the martyrdom of slaves are even more explicit. The Pelourinho [pillory] Suite, for example, the post to which the slaves were tied and tortured, promises the most intense pleasures. This imaginary conversion of slave quarters into places of delight, both culinary and erotic, not only encourages the fading of images of slavery in Brazil, helping them become increasingly remote but also, and principally, expresses the contemporary desire – sexual, but not only that – for everyone to be a master.

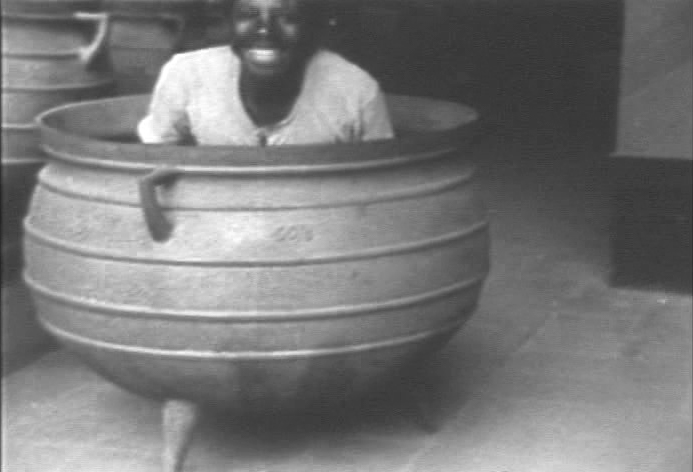

Scene in 1922: a exposição da Independência, a documentary by Silvino Santos recovered by Roberto Kahané and Domingos Demasi Filho

The Return of the Slave House

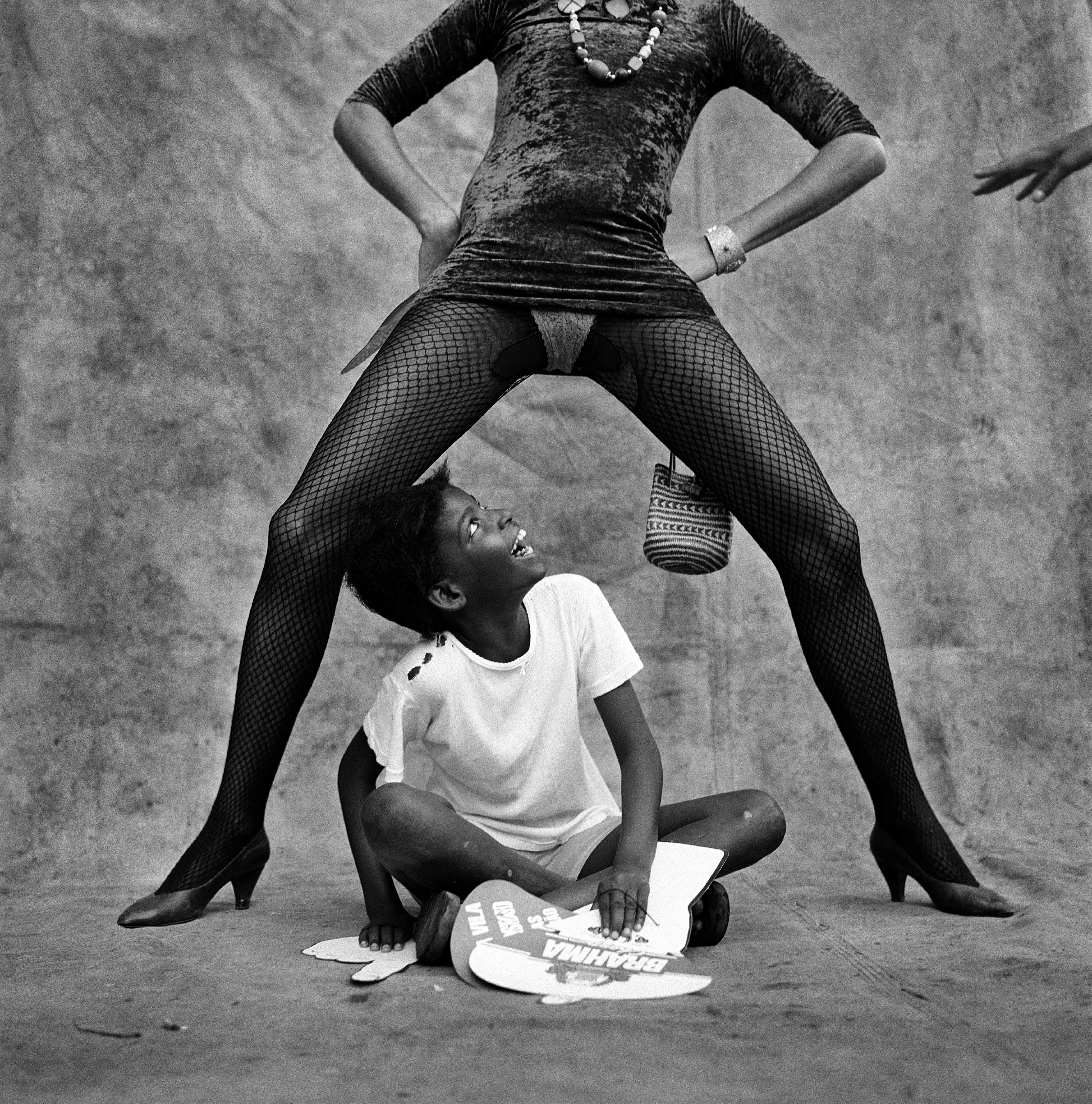

However, as we never cease to hear, nothing disappears completely from memory. And as Sigmund Freud said, the repressed always returns. A sudden appearance of the black man is scary, haunting, giving comic overtones to the social panic that the Brazilian urban middle class inherited from the old manorial estates. In 1922: a exposicao da Independencia [1922: the exhibition of Independence] – a documentary filmed by Silvino Santos in a large exhibition in Rio de Janeiro celebrating the centenary of Brazil’s Independence – a young black man suddenly emerges from a large clay vessel. It is the sudden appearance of this black man that, like a ghost, penetrates the skin of the present, as in Luiz Braga’s photograph of a port worker in the Porto do Sal [salt port] in Belém. Appearances like this occur repeatedly in Brazilian iconography, particularly in film. The sequence showing the birth of Macunaíma in Joaquim Pedro de Andrade’s 1968 film has its photographic counterpart in Rogério Reis’ well-known series of photographs of Carnival in Rio de Janeiro.

So, the ghost of the black in the slave house is not exactly invisible – even among the upper strata of modern Brazilian society – but submerged. This can be seen in the documentary record made by Marcel Gautherot of a miner in Pará, in 1950.

|

|

| From the Carnaval na Lona [Carnival on canvas] series, 1999, by Rogério Reis | Garimpo na foz do rio Tauari, Pará [mining at the mouth of the Tauari River, Pará], c. 1950. Marcel Gautherot/Instituto Moreira Salles |

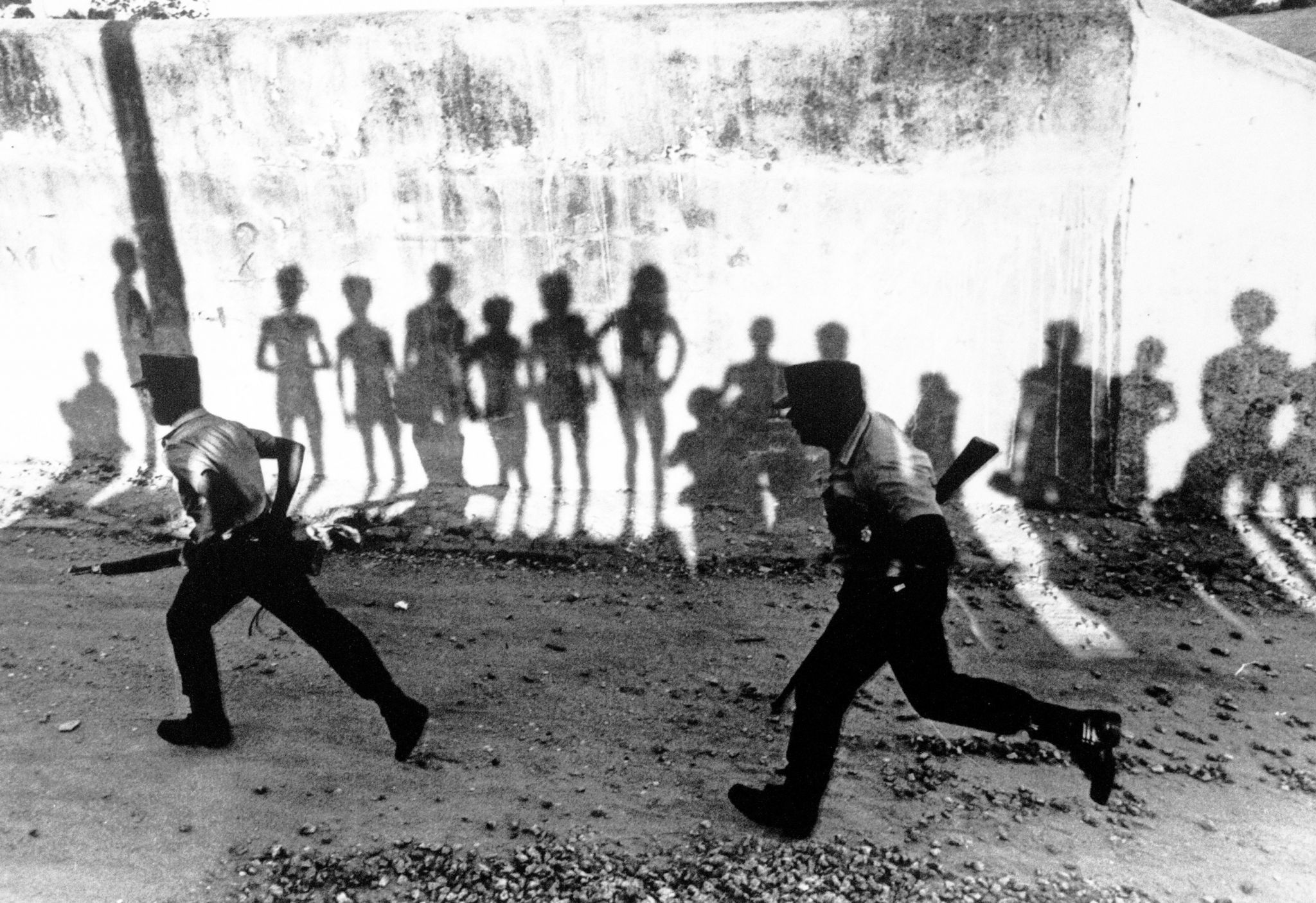

Estado de sítio [state of siege], 1977, Walter Firmo

There was no shadow more famous in Brazilian political history than that of Gregório Fortunato, former president Getúlio Vargas’ chief bodyguard and nicknamed “Black Angel” by the press. Son of a former slave, Fortunato ended his days in prison, accused of plotting an attack on Carlos Lacerda, Vargas’ political enemy. His celebrity, however, did not stem from this chance leading role. During the second Vargas government (1951-54), photographers always tried to include him in pictures because his imposing black figure served the opposition press as evidence of the hidden and corrupt side of the president’s power.

I think there is no more meaningful picture of the depressing situation of the absence of the black population from political leadership than a photograph of Evandro Teixeira, taken during student demonstrations against the military dictatorship in Rio de Janeiro in 1968. Ignoring the students, watched at a distance by a soldier armed with a rifle and bayonet, a city park gardener rests after lunch.

|

|

| Getúlio Vargas and his bodyguard Gregório Fortunato, archives of Jornal Estado de Minas/revista O Cruzeiro, 1950s | Movimento estudantil [student movement], 1968, Evandro Teixeira |

There is a submerged fraction of the slave quarters, a remnant that has not been completely consumed in the fire of merchandise. A residue left by an excess of horror, the unspeakable horror that the walls of the slave quarters failed to hide. In photography, this residual aspect usually manifests itself as irony (Evandro Teixeira), comedy (Rogério Reis) or allegory (Marcel Gautherot). But sometimes, the repressed returns violently: the shadow of slavery comes into the light, causing scandal and consternation. Even if the emotions they cause are fleeting, these images are permanently imprinted on the collective memory. This was the case with the photograph that won the Esso Award in 1983.

Luiz Morier photographed the police carrying out a raid in a Rio favela. That day, the number of arrests was so great that there were not enough handcuffs to go round. So a policeman got hold of a rope and the prisoners were taken away roped together. Morier called the photo Todos negros [all blacks], and it was impossible not to relate this police action to the capitao do mato [bush captain], a figure from colonial times given the task of capturing runaway slaves. This similarity was, of course, the reason for the award. A dormant, latent image, which materializes in equal measure in the police gesture, in the lens of the photographer and in the memory of the newspaper’s readers. At first glance, public outrage seems to be motivated by po lice brutality, but what truly shocks is the naturalness of the action. In other words, the way in which it is “natural” to relocate in the present images that history has accustomed us to see as from the past. The fact that prisoners were treated with disrespect is less of a reason for revulsion, I believe, than that police action reincarnating a dead image with real, living bodies.

Recently, in February 2014, a similar photograph dominated the media. A teenager suspected of stealing was captured and beaten by a group of residents of a middle-class neighbourhood in Rio de Janeiro. Then he was left tied to a pole with a bike lock around his neck. The association was immediate: the nudity and the irons that bound him to a pole on a public road was a contemporary vision of the corporal punishment that disobedient runaway slaves were subjected to. This photograph, in a way even more evident than that before, existed long before it was taken.

A strange destination, slave quarters. Its image, missing from the book cover, seems to have dissolved over time. But in fact it has been swallowed by the fantasies of the master’s house, which has become this imaginary place where we can fulfill our desires, the abode of our lordly illusions. Who would still be surprised by the inauguration of a Senzala Shopping Mall? However, the more the master’s house which dwells within us gives free rein to the imaginary omnipotence of our desires – desires that ultimately will never be fully satisfied –, the more real and violent will be the return of images of suffering that we were complicit in burying. The real violence of lost images in search of new bodies to reincarnate.

The image of slavery was banished from the cover of the latest edition of Gilberto Freyre’s book because the restaurant and the motel are the new faces of the senzala. Where before there was duality and tension, there is now unity and promise of enjoyment. All that remains of the original slave quarters are ghosts. Homeless souls, homeless ghosts that will always come back to harass us, dramatically and painfully, like a naked boy chained to a pole. ///

Mauricio Lissovsky is a historian, PhD in Communication, writer and script writer for the cinema and TV. He lectures on Script Writing and Image Theory at the Communication School in the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. He published Escravos brasileiros do século XIX na fotografia de Christiano Jr. [Brazilian slaves from the 19th century in the photography of Christiano Jr] (1988), A máquina de esperar [the waiting machine] (2008), Refúgio do olhar [the eyes’ refuge] (2013) and Pausas do destino [destiny’s breaks] (2014).

///

Get to know ZUM’s issues | See other highlights from ZUM #7 | Buy this issue