The body against the grid

Publicado em: 13 de April de 2023Since the mid 1970s, Gretta Sarfaty has resorted to several languages – photography, engraving, painting, performance, video – to critique the representation of women in society. Making use of the militancy arguments prevailing at the time or the resumption of the debate in the last decades, there is no doubt that her production can be interpreted through the eyes of feminism, although Sarfaty has never formalized her links with the movement. Born in Greece and brought up in Brazil since she was a young child, white and coming from a wealthy family, gifted with a stunning beauty, married and mother of three children by the time she was 27, the artist had to break with the family expectations of the roles she should play in her home and professional life. Her personal story is marked by challenge and rupture, which to some extent explains the autobiographical nature of her work.

However context of counter- culture. At the confluence, her rebellious spirit also had to do with a project shared among peers of the same generation in the of gender, racial, environmental, pacifist, and anti-capitalist struggles, attempts to oppose the power mechanisms responsible for maintaining the status quo were encouraged in different parts of the world at the expense of the oppression of the individuals and their dissent. In Brazil, as in other Latin American countries, there was also the need to resist the civil-military dictatorship, responsible for a lengthy legacy of state authoritarianism and human rights violations. For some Brazilian artists and cultural agents, the best way to show their resistance in their works was to challenge and even break the limits of institutions and the art market, inevitably connected as they were by their councils and networks of relationships to the regimes and their supporters. In addition to “dematerializing the traditional support” – as US critic Lucy R. Lippard noted in 1972 – it involved working as a group or anonymously, blending into the crowd, undertaking ephemeral activities in public spaces and sharpening a tactical sense in order to avoid censorship.

These were the environment and practices that marked the beginning of Gretta Sarfaty’s career in São Paulo. In 1978, she participated in the happening Mitos vadios [stray myths], organized by Ivald Granato, who had been her professor, and which consisted of a day of protests in a parking lot in Augusta Street. In response to the 1st Latin American Biennale, which was then in progress, the event brought together dozens of artists, including Hélio Oiticica, Lygia Pape, Regina Vater, Anna Maria Maiolino, Gabriel Borba and Artur Barrio, in front of an audience of passers-by. Sarfaty had already been showing her work in spaces dedicated to experimental art, such as Franco Terranova’s Petite Galerie in Rio de Janeiro, and the Museum of Contemporary Art of the University of São Paulo (MAC-USP), a true laboratory for artistic creation in its early years under the direction of Walter Zanini. This circuit was responsible for promoting production in new or little explored artistic languages, such as happenings and performances, urban interventions, video, photography and multimedia, that is: artist books, photocopies, stamps and other reproducible media, appropriate for conveying conceptual proposals and process recordings, as well as popularizing access to art. When invited by Terranova in 1976 to be the subject of an individual exhibition at the Galeria de Arte Global in São Paulo, Sarfaty showed her Metamorphosis (1973-1979) series, composed of fast and vigorous drawings of what she observed, foreshadowing the restlessness of ideas yet to mark her later work. The space belonged to the broadcaster TV Globo, and that’s why their agenda used to be shown during breaks in programming. Commercials became an opportunity to investigate the making of television, and the artist, testing spontaneous and non-esthetic “funny faces”, created a counter-narrative to a male-dominated media imaginary, responsible for stereotyping, eroticizing and objectifying women.

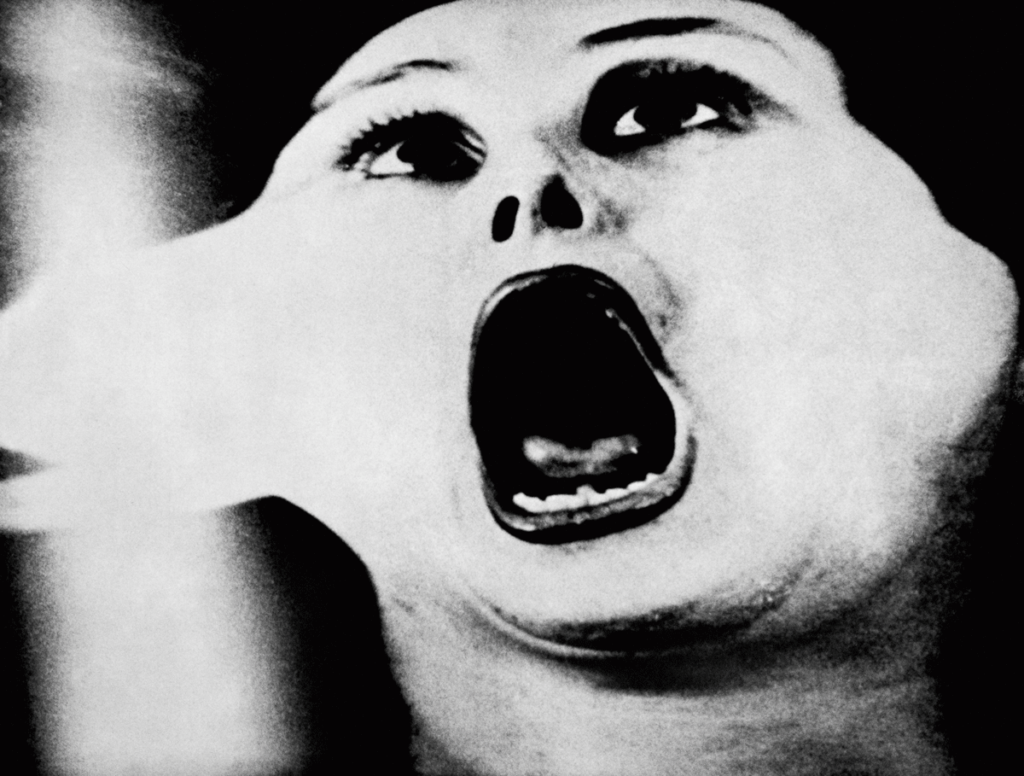

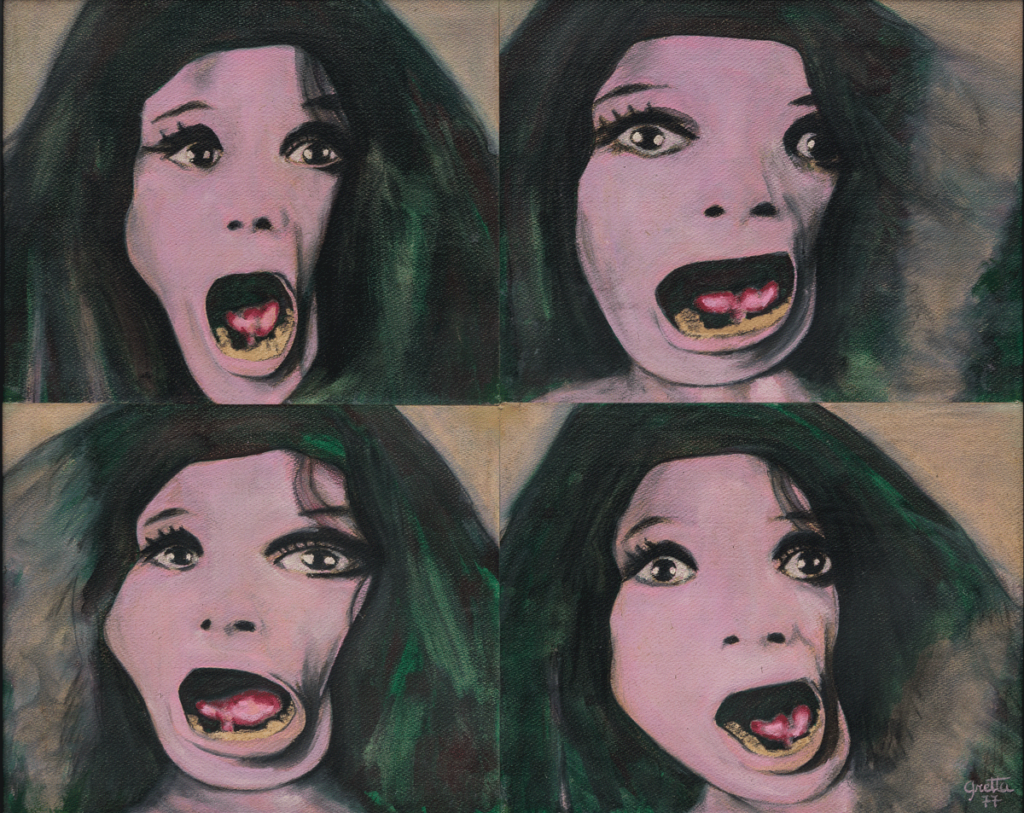

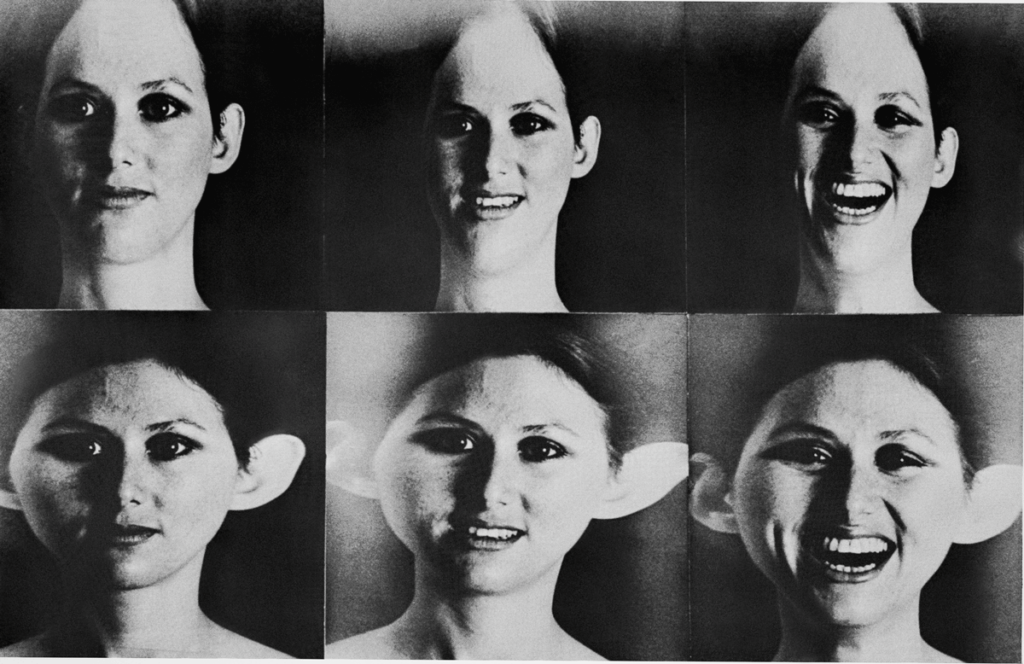

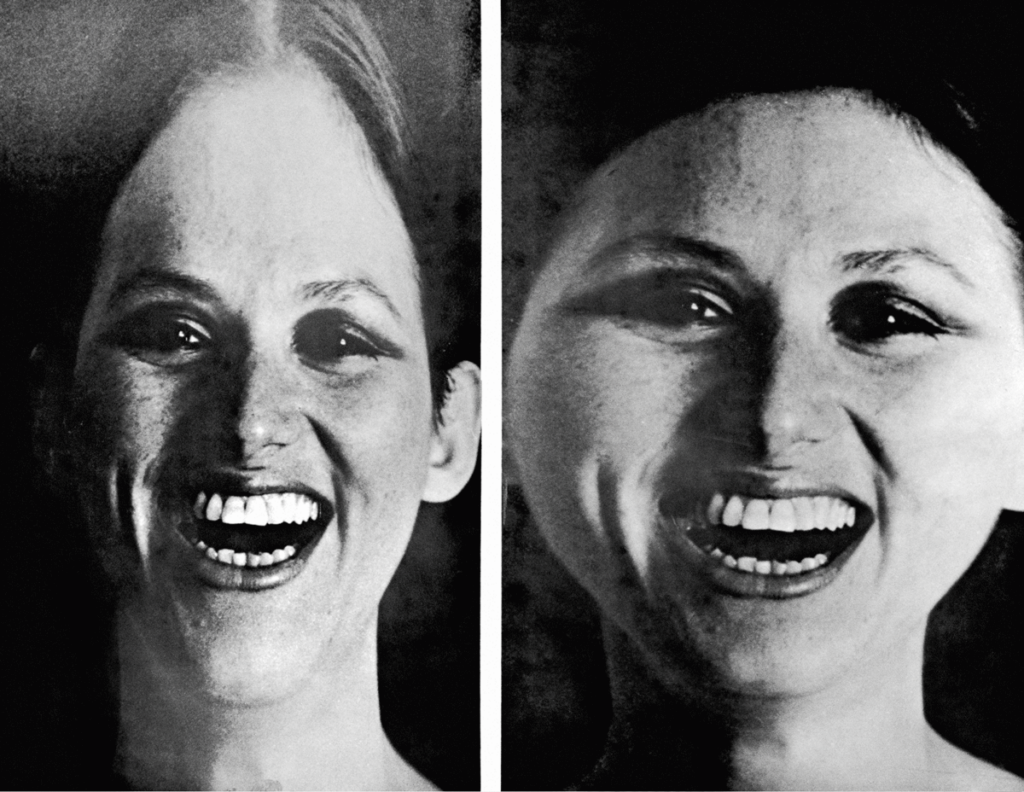

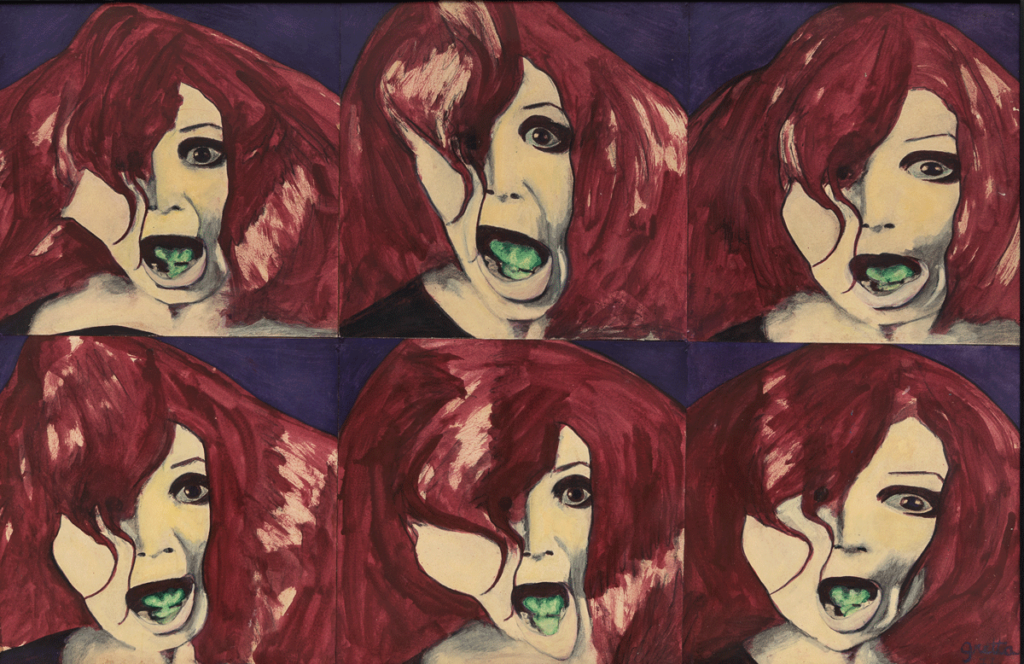

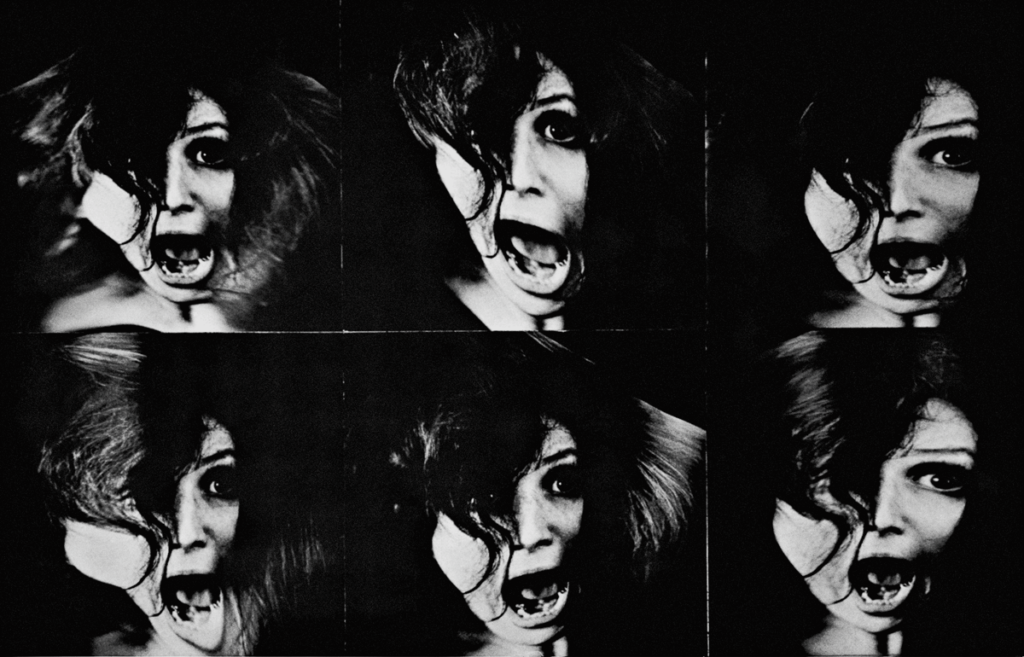

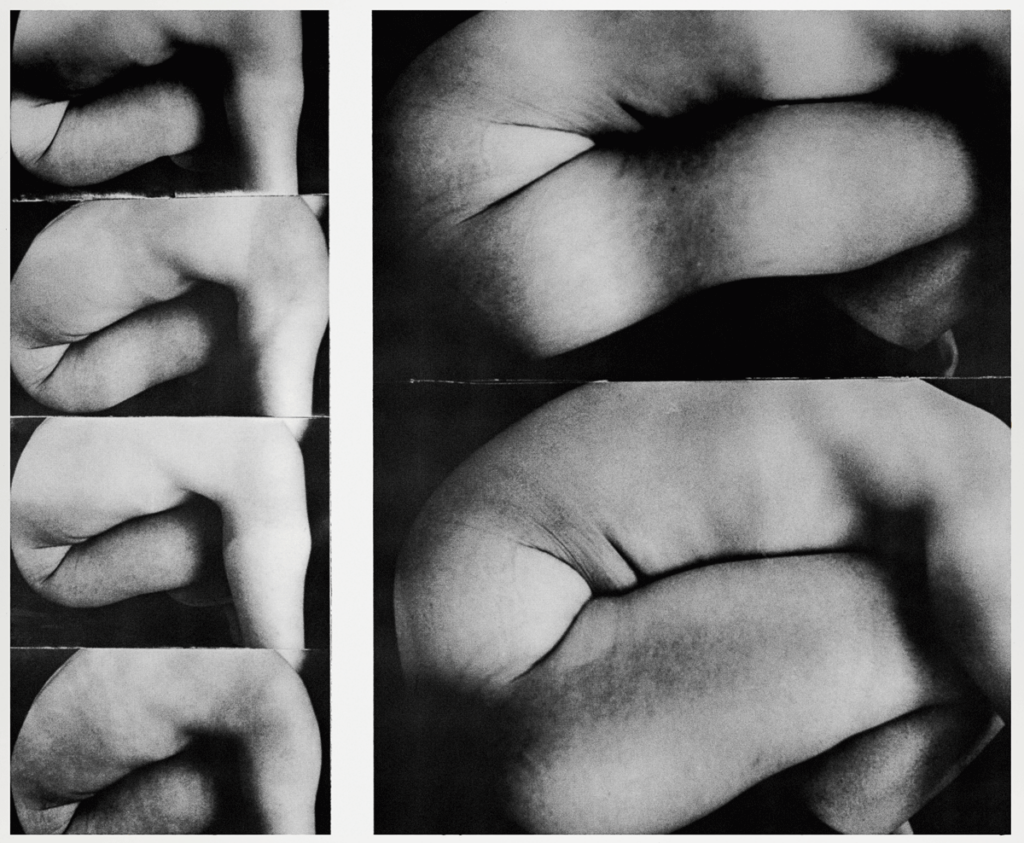

This episode acted as a trigger for Auto- Photos (1975), the first series of a fundamental collection of her photographic work conceived in that period, the images somewhere between a serious statement and mockery. With a minimum of makeup and outfit, she posed for portraits of various female types, in extreme close-up. She assumed both the role of model and art director, taking on the leading role of someone who, in that photographic series – as in life –, broke paradigms and was all or almost everything she wanted to be. Each type was mounted with nine snapshots arranged in an orthogonal grid. This organization suggests a sense of multiplicity and mirroring: they speak both of different women connected by gender-related issues and of various female archetypes living together and fusing their complexities in a single person. In this way, the sequences treat the portrait as a less assertive and more speculative exercise. The desire to cast doubt on a repertoire of representations motivated Sarfaty’s research into the post-production process in photography, for which she had the essential support of the architect and professor Julio Abe Wakahara. These investigations culminated in Transformations (1976), a simultaneous series which was in some way complementary to Auto-Photos. Taking analog portraits that she had already enlarged, the artist decided to produce even more provocative images. By bending parts of the paper and fixing them with metal thumbtacks, she created distortions in the images of her face. Rephotographed, the manipulated portraits lost their human contours, gained gigantic ears, flattened foreheads and cheeks shifted to the sides. Using extremely rudimentary methods, as in surrealist collages, Sarfaty’s handiwork explored photography as a technique and belief system – a system sustained by the false promise that the image can capture the real, when it is always subjective, relative, and ideological.

Among the many myths about women put about by the patriarchy, there is one in particular that this work shines light upon. It is the stigma of madness, a classic attempt to silence insurgent personalities by means of a diagnosis that de-legitimizes them even before they (or exactly not to) confront their arguments. Despite lighter and more amusing scenes, which show with playfulness the formal manipulations of the still-smiling artist’s physiognomy, the series gains dramatic intensity and revisits stereotypes to attest to female insanity: the staring eyes and the unkempt witch hair; the stifled cry trapped in the throat of the hysterical woman; the suffragan’s resilient confrontation of the veto; all open mouths, framed in close-ups; their cries echoing in many images, even if they are mute. From the way they are photographed, however, these gestures preserve ambivalence. They say as much about the fabled emotional torments projected onto women as their seizing back of a power that cannot be taken from them.

With these photographs and their ramifications, Sarfaty was ready to dispute the social imaginary of female madness. The migration of the series to drawing and dry point etching prolonged the time of the artist’s relationship with the scenes portrayed, allowing her to dive even deeper into the themes and taboos that they triggered. Her paintings for the series Transformations deepen the break with naturalism by means of vibrant fields of color that dialog with the detachment of pop art and the new figuration, but above all highlight the expressiveness of the figure represented. Sarfaty embraced her dramas and affections by means of this chromaticism, applied in loose and visible brush strokes. If the pictorial gesture resists in art history as an index of authorship, here it was used to mark the place of speech in a public debate. After performing, recording and editing these constructions of gender, the artist colored them by hand. By doing so she seems to emphasize her own pleasure to keep reinventing herself and enjoying the freedom to be monstrous.

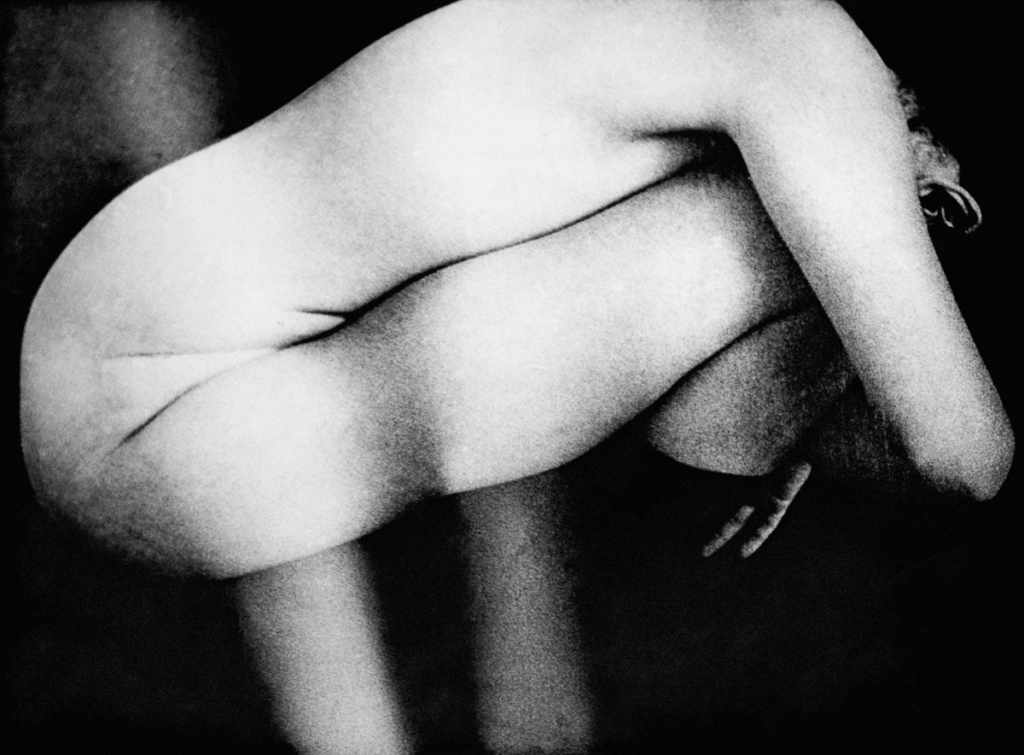

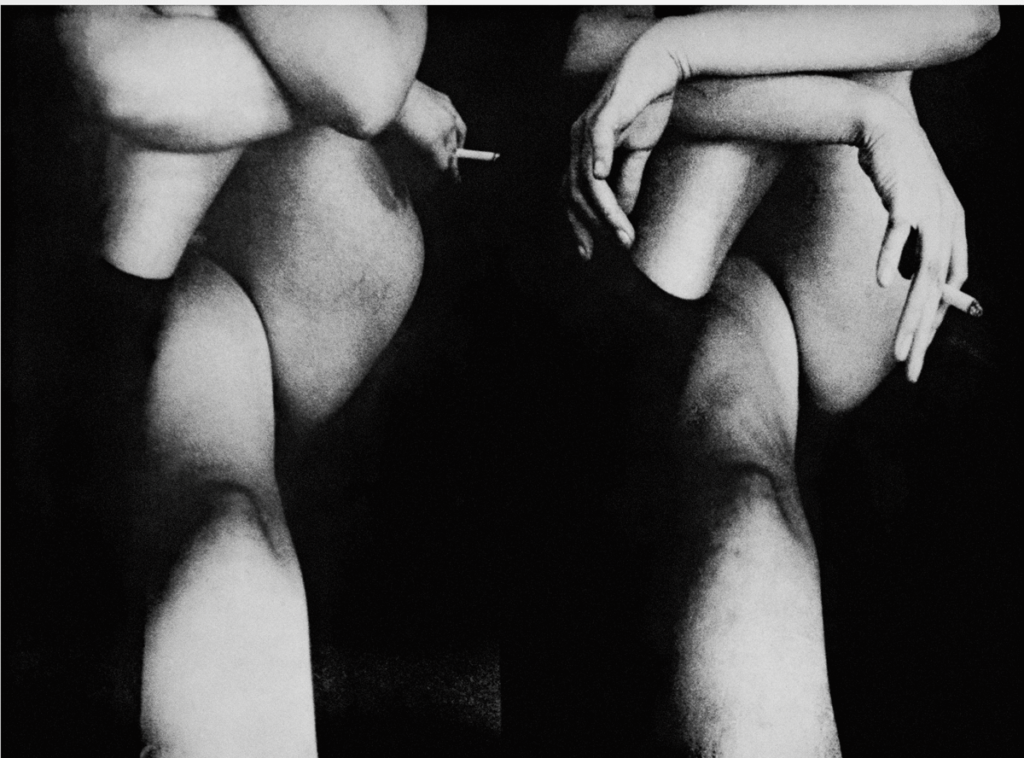

Any woman, whatever woman

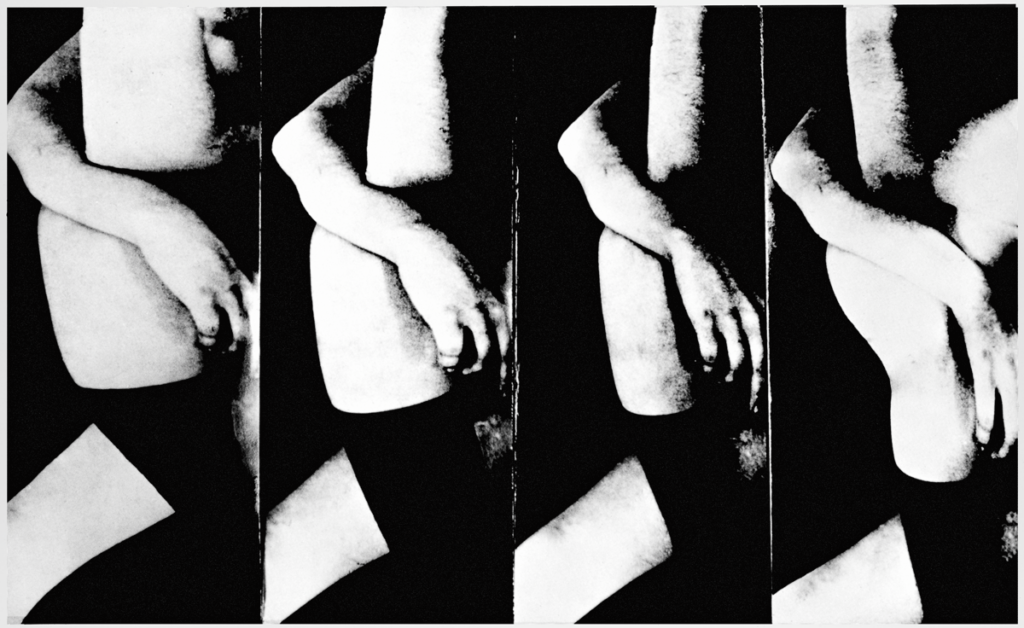

Throughout the 1970s, several artists experimented on their own bodies to demonstrate and criticize the cultural castration that comes from the condition of being a woman. In Brazil, along with Sarfaty, artists such as Vater, Maiolino, Letícia Parente, Iole de Freitas, Sonia Andrade, Anna Bela Geiger and Vera Chaves Barcellos produced iconic works in various media, especially video art. The emergence of the first portable video cameras made it possible the exercise of self-filming and, consequently, of breaking with the hegemony and hierarchies of audiovisual speeches made in an institutional or industrial context. In these works, the discussions about identity and resistance to forms of standardization focused on the face of the artists. If this is the point at which subjectivities are recognized and negotiated, what about the rest of the body and, consequently, the faceless representations? Differing in this aspect from all the other works of Sarfaty discussed here, A Woman’s Diary (1977) may offer some answers. In the series, the artist is photographed naked, in planes that fragment her body and always exclude her head. The framing, lighting and neutral studio background contribute to erase any evidence capable of contextualizing and singularizing her. Anonymous, she becomes again ambivalent: both an objectified body, subjugated in its generic form, and an empathic body, sensitive to what escapes from her. The sin of being an ordinary woman in the judgment of men runs in parallel with the possibility of being any woman, following the path of her own desire.

The images manage a nudity that does not serve the idealization of the idyllic body characteristic of classical art, or the fetish of the erotic body, constructed in film and advertising as a constant game of show and hide. Sarfaty established a direct relationship with the camera; she eliminated mediations and distances. Her photographic diary spoke of a policy of representations that only takes place in the presence and, therefore, presupposes active listening and the maximum complicity between the portraitist, the camera and portrayed, jointly responsible for the creation.

All these series demanded long periods of investigation, which lasted until 1986. In 1978, however, they were collected, at the stage they were then found, in the book Auto- Photos, published by Massao Ono, an important editor of the independent market, including books by artists. At that time, Sarfaty was already dividing her time between São Paulo and Milan, until, in 1983, she moved to New York and drastically reduced her personal and professional contact with Brazil. Those almost thirty years of self-exile may explain the lack of awareness and historiography of the artist’s legacy in the Brazilian art world.

Her return in 2015 re-established interrupted processes, which involved making known those works which had rarely been shown but were already to be found in the collections of museums; locating records and projects in their documentation centers; rebuilding connections with the institutional and commercial art circuits; and increasing the dialog with other generations. The re-publishing of Auto-Photos in 2021 is part of this movement, still in progress, to make a reunion between Sarfaty and Brazil, critics, the public and the current issues of feminist art. In this state of entropy – when the identity agenda and gender activisms strengthen, while at the same time a swerve to conservatism, backed by the federal government, becomes explicit – dialectics and disobedience remain important driving forces. For new or old reasons, the structures continue to inform the body, and the body remains eager to transform the structures. ///

+

Auto-Photos, by Gretta Sarfaty (Central Galeria, 2021)

Ana Maria Maia (Recife-PE, 1984) is a researcher, curator and professor of Contemporary Art, with a PhD in Arts from Universidade de São Paulo (USP). She is the organizer of the book Flávio de Carvalho (Azougue, 2014) and the author of Arte-veículo: intervenções na mídia de massa brasileira [arte- veículo: interventions in Brazilian mass media] (Circuito e Aplicação, 2015). Since 2019, she has been a curator at the Pinacoteca de São Paulo.

Gretta Sarfaty (Athens, Greece, 1947) is a painter, photographer and multimedia and sketch artist. She became a naturalized Brazilian citizen in 1954. In 1970, she participated in the Grupo deVanguarda in Rio de Janeiro with Cildo Meireles, Artur Barrio and Rubens Gerchman. She has had works exhibited at the São Paulo Museum of Art (Masp), the Moreira Salles Institute (IMS-SP and IMS-RJ), the Museum of Modern Art of the City of Paris and the Georges Pompidou Center in Paris, among others.

Originally published in ZUM Magazine #23, October 2022

Tags: revista ZUM, ZUM 23