Black power

Publicado em: 7 de June de 2022A black man who records his peers with a camera is a conquest. The under representation of Brazilian Black art in collections, museums, galleries, festivals, exhibitions, publications, and curatorial projects is evidence that the work of white Brazilians continues to dominate the visual arts.

If this Black guy is the son of a laundress and a docker – and he is happy to talk about his origins – and was born in Fazenda Grande do Retiro on the outskirts of Salvador, in the Todos os Santos bay, entering into the world of the arts is as challenging as organizing his artistic and political project. Lázaro Roberto dos Santos has included his work in the Zumví Arquivo Afro Fotográfico [Zumví Afro Photography Archive] since the 1990s. Starting with donations from personalities such as Jônatas Conceição, an activist in the Movimento Negro Unificado [Unified Black Movement], Luiz Orlando, a researcher into Black cinema, and photographer Rogério Santos, the Zumví today houses about 30,000 photographs from the collections of eight photographers. Two-thirds of them were taken by Roberto. They depict the work, daily life, the political and social struggles of the Black movement, popular and religious festivals, the remaining communities from quilombos [rural communities originally founded by escaped African slaves] and Black aesthetics.

The archive project is the result of the encouragement of militants Raimundo Monteiro and Aldemar Marques, who wanted to give visibility to the Black memory and history of Bahia and found in Roberto the ideal partner. When the two comrades left the project, it was up to Roberto to take it on. Aware of the relevance of the material, which was stored in precarious conditions, Roberto sought the help of his nephew, historian José Carlos Ferreira, who became executive producer of the archive. To bring Zumví to life, they wrote a manifesto and went in search of institutional support. However, they were received with disdain at first and a series of bureaucratic barriers, as well as empty promises.

Now the project survives with the help of a few close supporters, public funding from open funding calls, and the hope of keeping alive the memory of the Black population through Black lenses.

In the 1970s, Roberto was a member of a theater group set up by the progressive priest Paulo Maria Tonucci, who aimed at denouncing social misery, confront the military dictatorship and offer artistic and cultural training opportunities to the community of his local parish. There, at an annual arts festival, Roberto saw some photographs that immediately caught his attention. He began to take photographs using a camera borrowed from Geremias Mendes, responsible for recording the work of the group headed by Antonio Jorge Godi. Not knowing at that time what the future fate of these photographs of the neighborhood, of people, of parties, of demonstrations might be, he kept them so that the images of that period could be seen again in the future.

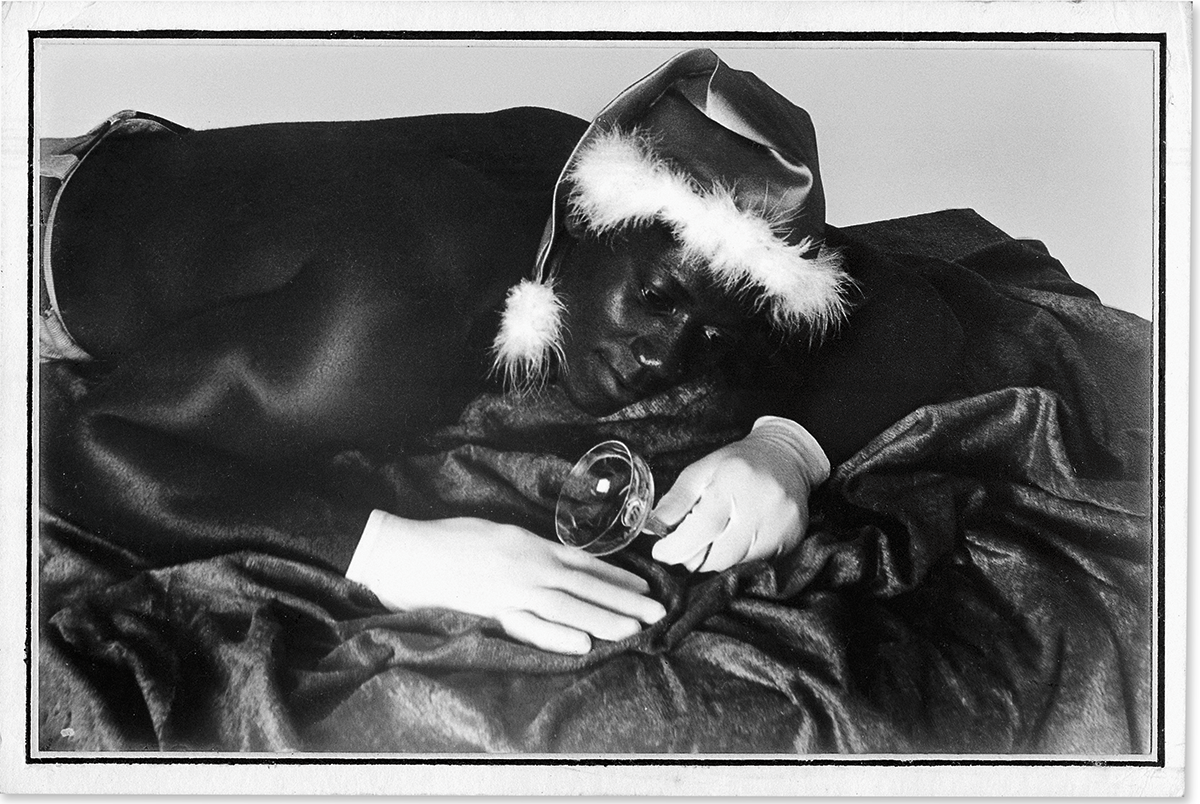

His images expose the structural racism, either by portraying homeless Black people or responding to the growing intolerance against religions of African origin in Brazil – as in the picture of the young man with the poster “Exu is not the devil. Respect my (sacred) beliefs.” Roberto’s photographs contrast the harshness of life with the broad smiles which celebrate the festive ethos of the Black people. He avoids taking stereotyped images, which sell sinuous bodies and toned muscles, to show the subjective strength of Afro hairstyles and hair.

Roberto is a sweet, attentive and unwavering man. His modest demeanor does not hide the marks of past suffering, which he reverted into energy to absorb the Black world and present it in photographs. In our conversation, Roberto shares his references and the process of creating a look that reflects in the encounter with the other his Black people, whom he wants to cherish. With one eye on the past and another in the future, Roberto highlights the educational purpose he wants to achieve with his work at Zumví. His voice enthusiastically reaffirms the militancy that flows in his blood, in the images he produces, in his body and in the look at the diaspora.

When did you realize that photography might be your artistic language?

I was twenty years old and was taking part in the theater work of the Experimental Arts Group in Fazenda Grande do Retiro. They ran an annual festival for artists to show their work. There was an exhibition that year of the work of the filmmaker Antonio Olavo, who I came to meet only recently. They were images of cangaço [banditry in the backwoods of northeastern Brazil], of sertão [the backwoods]. I have never seen those few black and white images again, but they had such a strong impact on me that I tried to find out how he had taken them and began to wish to become a photographer.

Was that how you made the leap from theater to photography?

Yes. I immediately started to follow Geremias Mendes’ work, my colleague in the group. He used to photograph the shows, our activities, and would lend me his camera sometimes. I started by photographing people in the neighborhood, the city’s celebrations, our daily lives, until coming back from a trip, Antonio Godi, the group’s director, brought me a camera he had bought abroad. It was my first camera.

And how did you become a documentarist of the Black people and their history?

I was then working in a printshop with Father Paulo Maria Tonucci and came into contact with some leaflets promoting the Movimento Negro [Black Movement] which we were printing. The way I saw the world started to change and I realized that us, Black people, only saw ourselves in our ID photographs. I felt like doing something with photography to change this perspective. I didn’t see any Black people with cameras. Moreover, I was interested in the political issues of the time and the situation of the country, and this included the invisibility of the Black population.

How did your own story influence your photography?

My mother only knew how to sign her own name, but that did not prevent her from doing everything possible so that her eleven children could study. Some of us only got as far as high school, like me, because our lives were difficult. My sisters helped to look after the younger kids so that my mother could work. At school I used to get excited about the history of Brazil told by the teachers. In the evening, we would sit with the older people to hear their stories. I believe that the stories and my studies led me to be- come an arts educator and photographer. In photography, we accumulate memories and tell stories. All the family and school situations really contributed a lot so that I take photos the way I do. When I got my hands on the camera, everything in my life somehow became an image.

In what circumstances did you realize that you were a Black boy?

I always knew. Faced with the reality of my life in the 1960s and 70s, I always realized the difference between being a Black boy and being a white boy. It’s not that different from the present day, even if things have changed a little. Until I was about fifteen, I carried a lot of white people’s dirty clothes on my head for my mother to wash. We become more aware.

What self-image did your awareness of being Black produce in you?

A lot of African issues kept coming up until I began to realize that I had changed, and that is why there was in me a Black assertion. When I look back, I know where I come from, I know that my parents were Black, that we were in a Black neighborhood. These elements helped me develop affirmative values and were later to influence me to join the Black Movement. But I don’t think I really developed my self-image until I was a teenager. It was only after that that I became restless, I started to assume my blackness and to understand those Black Power people I used to see on the television, the strength of Ilê Ayê [a Carnival group, or block], which began close to where I was born, and what these African blocks meant to Black culture, influencing even how I managed my own hair.

We know that hair and elaborating hairstyles are the result of ethnic heritages, and that the designs of the braids, for example, have also already acted as a communication strategy. How do the aesthetics of your photographs of hairstyles take on ways to communicate with the Black people?

Black aesthetics images began to be produced at my own house, when I saw the straightening irons my sisters used to straighten their hair. Black kids have to live with prejudiced phrases about their hair, especially at school and in places where they play. I photographed every type of hairstyle in portraits and close-ups: Black Power, straightened, dreadlocks, and all the modification young people do to their heads nowadays. Every day I say that what I do could be in the schools.

So, is your photography also educational?

Although I had an exhibition called Qual é o pente que te penteia? [What is the comb that combs you?] (2017) at the Pierre Verger Foundation, curated by Alex Baradel, I’ve never managed to do something more didactic, educational even, about the theme of Black aesthetics in Salvador. These images could be made available to all public schools to bring about discussions about representativeness.

The curated exhibitions are really important, but we have never managed to show them for a long time and in other spaces. The photography I do is based on an archive that can make a real contribution to Law 10.639/2003 [which deals with the teaching of Afro-Brazilian and African history and culture]. The educational side of my work is a choice so that Black people can see themselves in the images.

In that sense, how does the self-portrait build your image?

I’ve never taken many self-portraits. One of the only ones is one where I pose with dreadlocks and a camera. I like this photo as it is a symbol of my story: a Black man looking into a mirror, for a Black photographer. I feel I am part of the Afro-Brazilian culture. But we never saw ourselves before, and we didn’t have photographs of relatives, of our ancestors. Photography was just for white people.

Is the story of your life a reference to your photography?

My mother, Valdelice Ferreira dos Santos, was a Bantu Black woman with very thick lips. She didn’t speak much. Like most Black women in the outskirts of Brazil, she divided her time between the house and work. My father would leave in the morning and return at night. Because he was an alcoholic, my mother wouldn’t tell him about any day-to-day problems. He was a rough man, who had grown up mostly without his parents, abandoned to the streets of the Recôncavo district. He was very closed in when he wasn’t drinking, but he loved throwing parties. They were happy parties, with lots of friends.

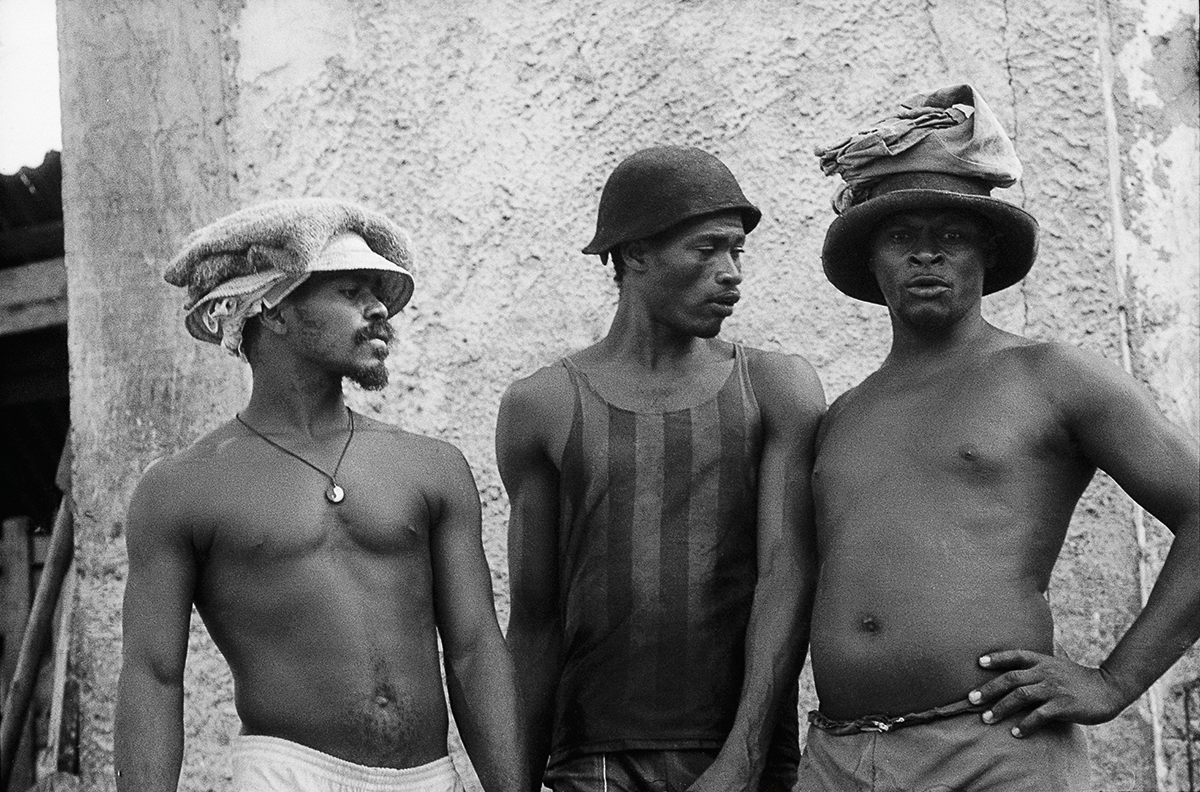

When I go out and photograph those workers, those market porters at the São Joaquim market, I think a lot about my father, José dos Santos, and the survival condition of the enslaved people, still waiting for an abolition that didn’t happen. They are all Black men doing very heavy work, really backbreaking. This can be seen in my photographs.

When I photograph people’s heads, I’m making a reference to my mother and the clothes bundles we used to carry together. It’s almost a fixation for me. It’s the head which carries a basket, which carries a pan, which displays some hair, an entire aesthetic. All of this is in the series Cabeça Identidade [Head – Identity].

The head is a sacred element in the culture of candomblé terreiros. How do the mythological connections with African roots appear in your work?

I learned a lot from my ten-year experience in a candomblé terreiro [place where the rites of the Afro-Brazilian cults are celebrated]. I have learned so much that I prefer to photograph this religiosity, which is also on the streets, at the popular festivals and at Carnival. The street is a public space. Of course, I had the opportunity to photograph in the terreiro, but I did not want to photograph the embodied deities, for example.

You knew Pierre Verger, who was responsible for an important photographic record of rituals in Brazil and Africa. Do you see any appreciation of Afro-Brazilian culture in his work?

Pierre Verger was a very polite man. I was introduced to him at Balbino Daniel de Paula’s terreiro, Obaràyí de Xangô, by the German ethnomusicologist Angela Lühning. She came to research music in Brazil, and eventually focused on studying the music of candomblé, becoming a good friend of Verger’s. When I worked with Jorge Batista in researching the professional heredity of the Água de Meninos market – which moved to the São Joaquim market in 1964 because of a fire – Verger gave us some photos to include in the exhibition. He liked my work. We ended up swapping photographs.

His work is didactic in nature. He researched a lot and used to take mail from the candomblé people here to Africa. This work is very much present in the academic field, for anthropologists, sociologists, historians, but it doesn’t filter down here, you know what I mean? Because it also brings with it some contradictions. He came from a rich family and was taking photographs for a long time, but did not see racism in Brazil, did not show people on the streets, living badly. But he did a very important job for a Black culture that needed to be recognized and contributed a lot for us to under- stand our roots.

Pierre Verger, Mario Cravo Neto and José Medeiros entered the universe of Afro-Brazilian religions in different ways and with very significant photographic results, each in their own way. They were all white men. What is it like for a Black photographer to be part of these symbolic and cultural resistance territories?

It is very rare to see a Black photographer document candomblé. Even with access to the spaces, the most famous works are those taken by white photographers. A new generation of more aware and concerned Black photographers is emerging, who are not taking advantage of such an important cultural manifestation as a trampoline or seeking to portray this theme from a perspective of someone who is not part of the Black population, even while respecting the sacred space. For example, Charles Bahia, who, like me, was a percussionist and born and raised within candomblé, has always done social photography, documenting the ceremonies there, without any intention of transforming his work into books or exhibitions. I don’t like those photos that we see in books about the people of the spirits. I think they appeal to the “exotic”. And we no longer want to be treated as exotic objects.

What is your relationship with religious traditions? How does knowledge of the religion foster further deepening of photography on this subject?

I attended the Ilê Axé Opô Afonjá in Salvador for a decade and became a probationary ogan [an assistant in the ceremonies] but I did not go through the initiation rituals to confirm me in that position. My family has always been divided between the Catholic church and candomblé. My mother was a daughter of Oxóssi and Omulu, while my sister was one of the founders of the neighborhood church. At the same time, we would all go and see the procession of iaô and the orixás festivals in the terreiro. But now the candomblé groups have moved to farther away places in search of better conditions.

You present the Black body as an ancestral phenomenon. How do the body and ancestry express themselves in the photographic image?

Ancestry is expressed in the body by means of gestures, in the way something colorful is tied to the head, in the way we dance, walk, eat, carry something, or speak. It is a knowledge that is transmitted down over time. Something so natural that Black people don’t even realize it. That’s when photography makes everything clear. However, people ask me if the photographs were taken here or in Africa, because there is a generally held view that the Black body is subjected, thrown in the streets, that it is the body of workers who continue to suffer with all this load of the bodies that preceded us, who were trafficked, violated by slavery. When I freeze the moment, I realize that our ancestry transcends Africa, but it still remains here. This is the body of the Black diaspora.

How is the Black body depicted in Brazilian photography in general, and specifically in your work?

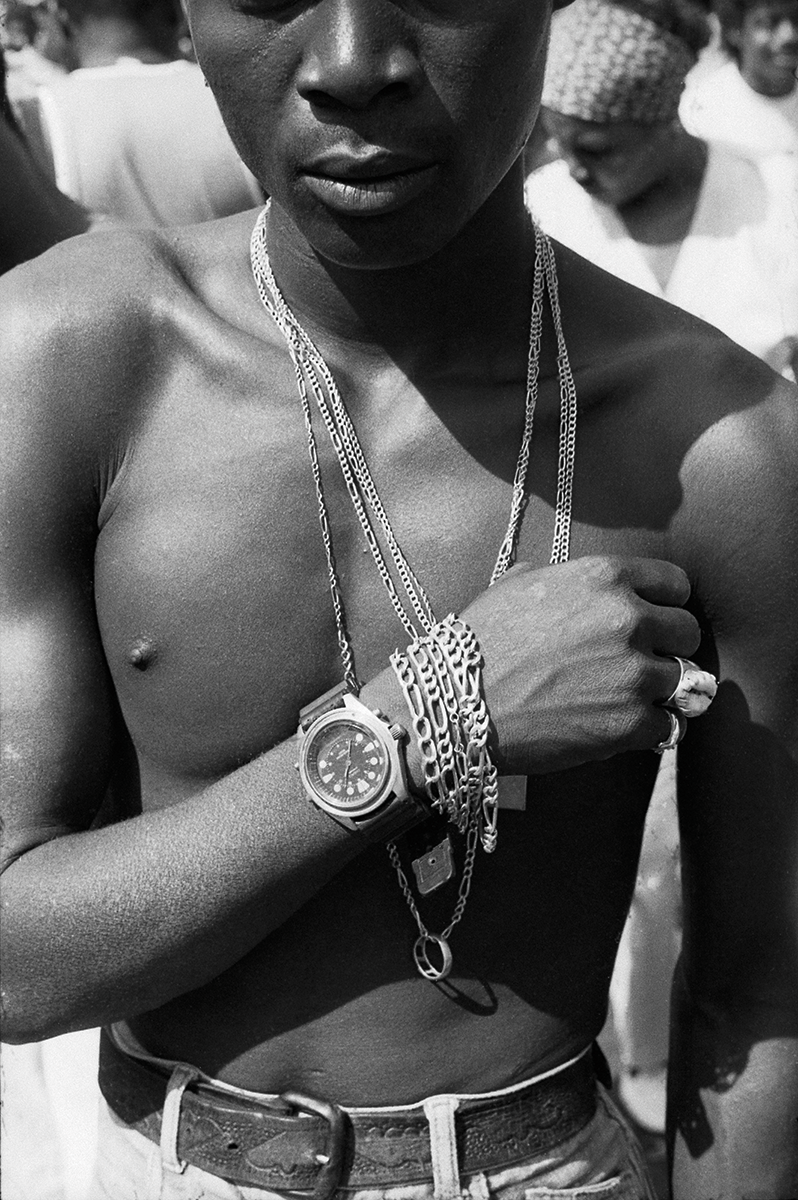

Overall, I see a very respectful job by the Black photographers who do this kind of documentary. I have this concern to do a job that brings information which is affirmative and which can be presented in the classrooms to generate discussions about the history of the Black people. It is my duty to have a more careful viewpoint than photographers who work with fashion and advertising, because my concern is with the is- sue of memory, of history. I fight against the extermination of Black bodies, coming from the awareness of identity. When I photo- graph a boy wearing lots of rings, I see that all his richness and nobility are represented there. That’s the area I work in.

Would you classify your photography as activist?

No. I prefer to call it affirmative photography. I think this has started to have an effect especially on new photographers. We have become a point of reference for other archives, such as the Arquivo Atlântico [Atlantic Archive], an experience inspired by Zumví.

One of the purposes of your work is to give visibility to Black people, but is there a specific language so that the images meet that purpose?

My work is an archive, but I do not take photographs so that it can be preserved. I need to shine some light on the great struggle of men and women, in images alluding to themes that value Black people. It is my job to make characters such as Zumbi dos Palmares visible, as well as Dandara and Zeferina, the female warriors, who have been forgotten in the official historiography. It is to show the demonstrations in favor of racial quotas for the universities in 2005, because at that time less than 1% of students at the Federal University of Bahia were Black. It is to show Chico Tomé, in the municipality of Rio das Rãs, the first quilombo to be officially recognized in Bahia. These are the banners that my photography waves. I have photographed the Afro and Afoxé blocks at Carnival since the 1980s. They’ve changed the face of Salvador over these forty years. The same is true of the São Joaquim market. I try to create a memory of post-Abolition times, photographing this theme in the streets. It is in these works that I feel represented.

Do you follow Black photography, that is, taken by Black men and women photographers or that have Black Brazil as a theme?

I haven’t really been following the Black photographers movement. When I started, Black people with a camera could not be seen, but today there is a generation of very young Black photographers, a good harvest, which will surprise us. I would like to give you three names here from Bahia: Alberto Lima, who has already been working for a while, with a focus on the Afro blocks and with Black personalities; Helen Salomão, whose work with fat Black women is very visible; and Jô Almeida, who works with Black aesthetics and is directing documentaries. There are many others, who work mainly in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo.

Do you perceive a Black viewpoint in the images of those photographers?

I will repeat what photographer Januário Garcia used to say: there is no Black photography, there is a Black viewpoint. I accuse racism of everything I’ve seen, while a white viewpoint may not know what I know. I see that in the images. Now, with a certain projection, with galleries calling and getting interested in my work, I realize that these visions I manage to place in the images were already formed in my head and in my ways of looking.

Are there curators interested in the decolonial perspective of your work?

Since 2018, I have been invited to present my work in projects led by Black curators. Diane Lima took me to the Valongo Festival in Santos, in São Paulo state (SP). It was the first time I left Bahia. She also took me to the Arts Triennial at Sesc Sorocaba (SP) in 2021. Tina Melo curated the exhibition Memórias de resistências negras [Memories of Black Resistance] at the Afro Museum of the Federal University of Bahia. It was about the forty years of the Black Movement and is based on the Zumví Archive. She also edited our catalog, which was launched with financial support from the Aldir Blanc Law [an emergency Federal program providing financial support to the cultural sector during the COVID-19 pandemic]. Recently, Hélio Menezes invited me to include works in the exhibition Carolina Maria de Jesus: um Brasil para os brasileiros [Carolina Maria de Jesus: A Brazil for the Brazilians] at the Instituto Moreira Salles in São Paulo. This is very important, because Black curators are also interested in our memories.

I began to see cracks in the hegemony from the moment when the work of Black people is shown. It is only over the last ten years that I have been exhibited more. That has changed my expectations, because until then I thought Black photography was not to be sold to art galleries. Until then, my photographs were only used to illustrate books and simple things.

The historical importance of your photographic archive is undeniable. If you could curate an exhibition, what themes would you propose?

I would choose the Afro blocks in Bahia and the Black aesthetic, as I’ve already mapped out the history of these themes in my head. As almost forty years have gone by, this exhibition would show changes in events and people in the city of Salvador. We dream of creating a museum of memories of Black resistance, where we could develop our own curatorial projects.

What are the needs and challenges needed to keep the Zumví archive going?

Our needs are many, and the challenges too. Experts in collections are helping us understand how to professionalize access to the archive. Recently, we received resources from an open funding call from the Bahia Secretariat of Culture that will allow us to digitize 15,000 frames. With that, we will hire interns to clean, catalog, store and treat the images.

We still need an appropriate space, because everything is still stored in my home, which is small and doesn’t offer the right conditions. Collective funding has allowed us to rent a space in the district of Santo Antônio in Salvador to sell products, provide services, receive the public and mount exhibitions. Photographs, postcards, t-shirts, stickers can also be purchased from the webshop, available on our site. We would also like to create the Chá de Memória [Memory Tea] and invite people who have been photographed to tell their stories. But everything depends on financial resources. We hope that will happen. ///

+

Zumví address: Ladeira do Carmo, 28. Santo Antônio, Salvador – BA. Site: zumvi.com.br

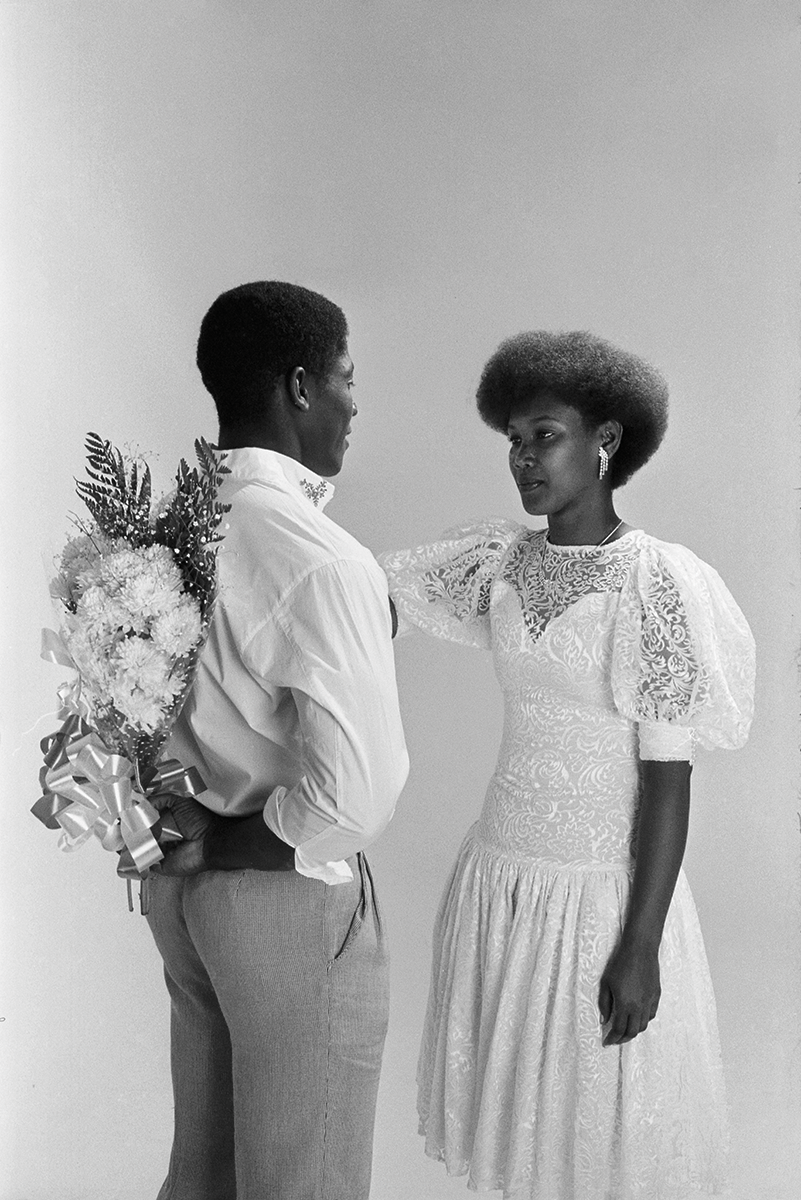

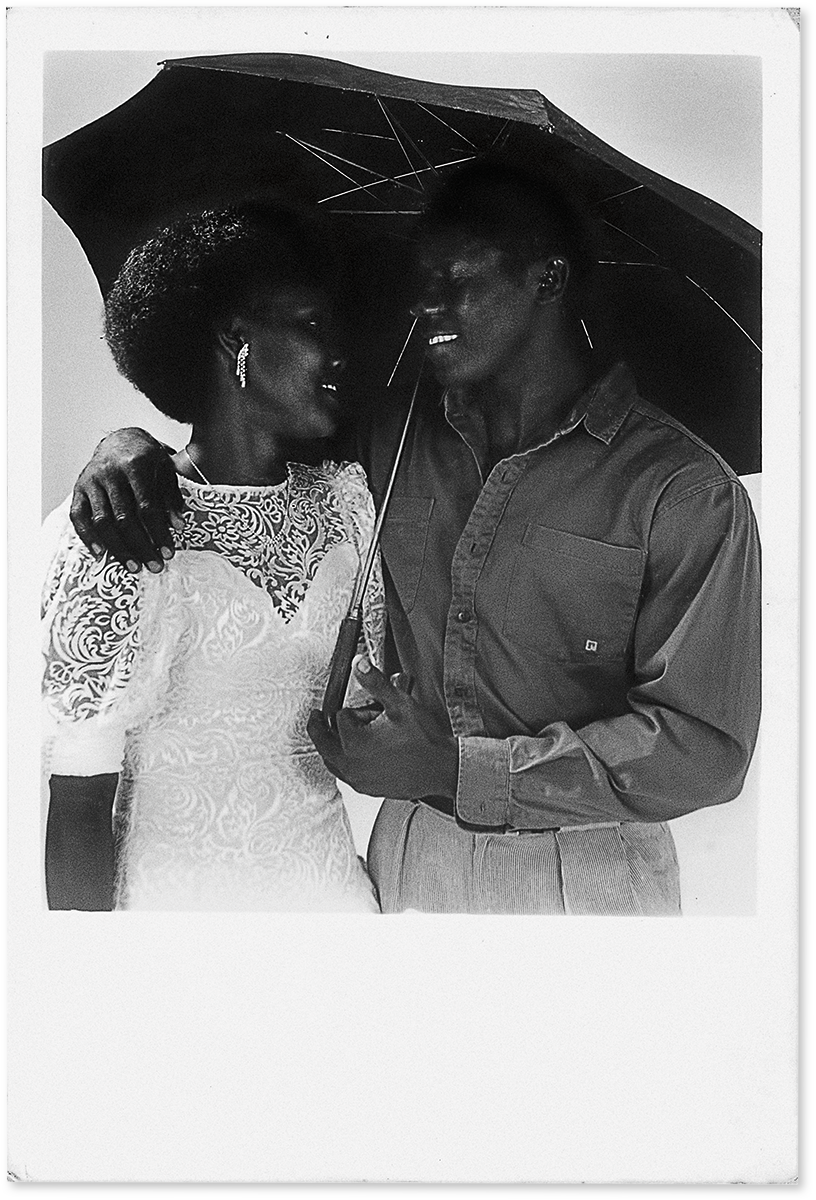

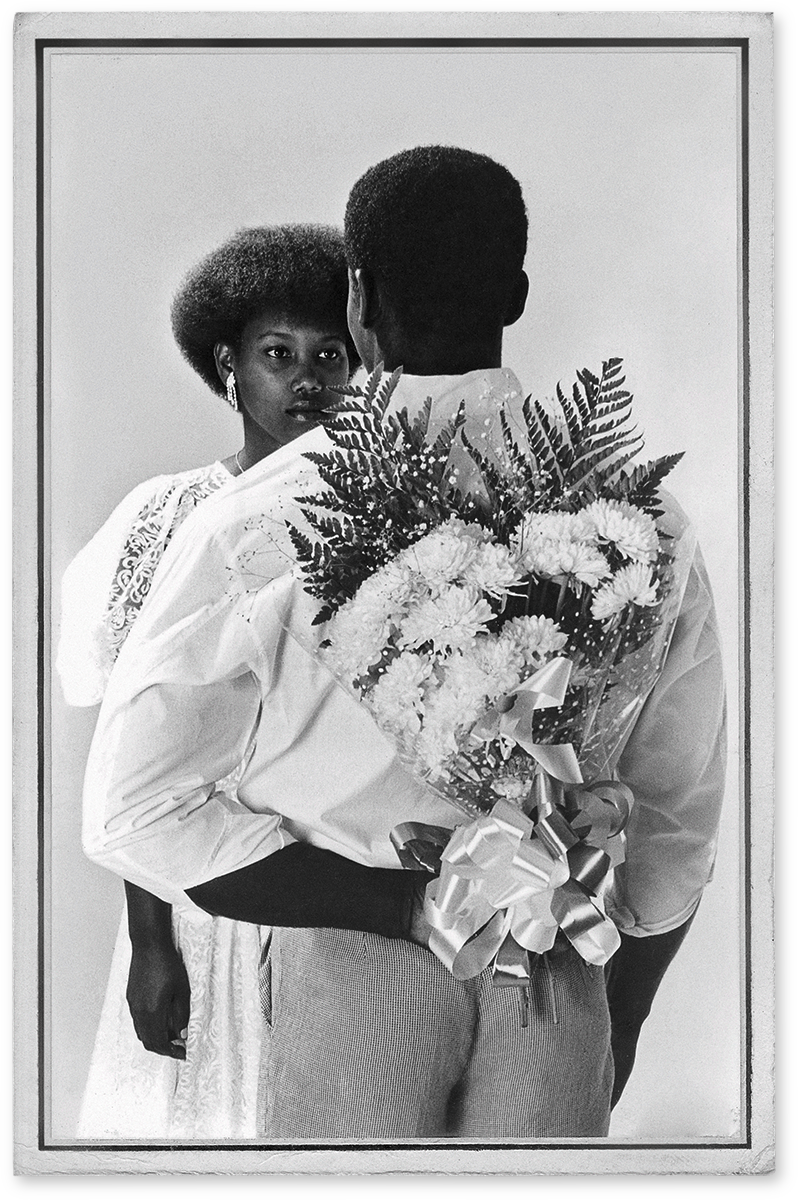

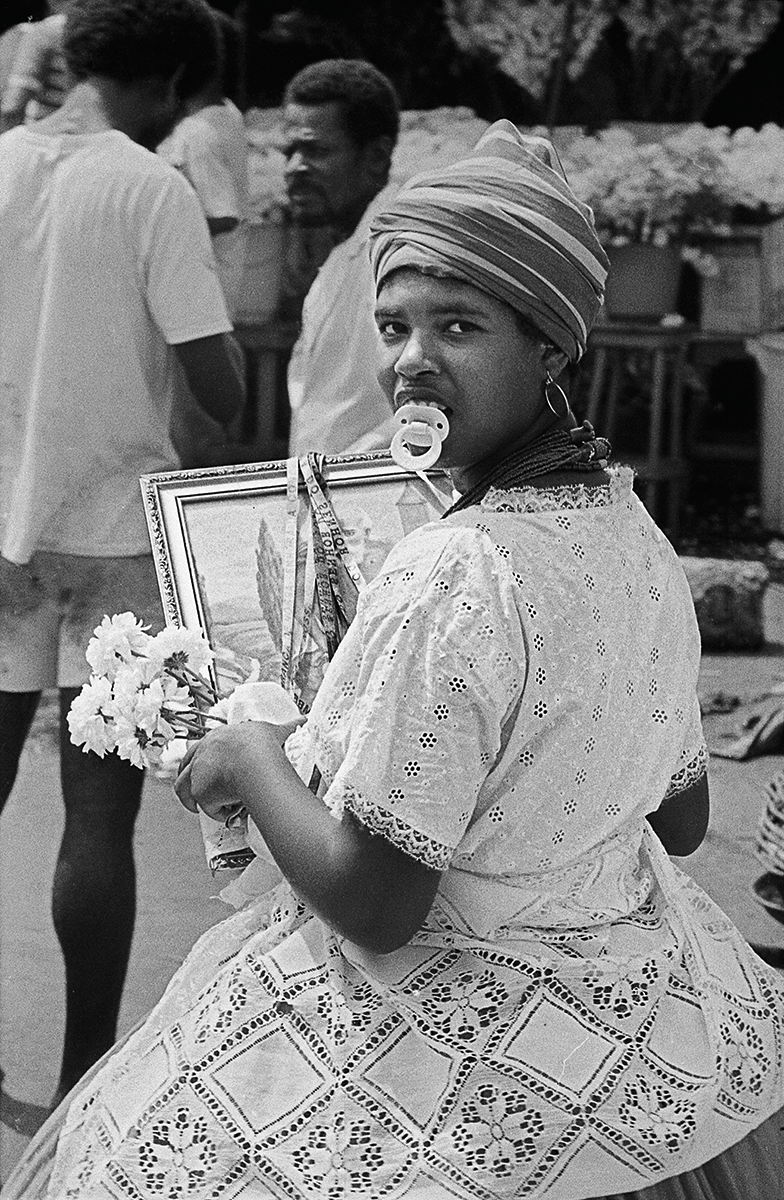

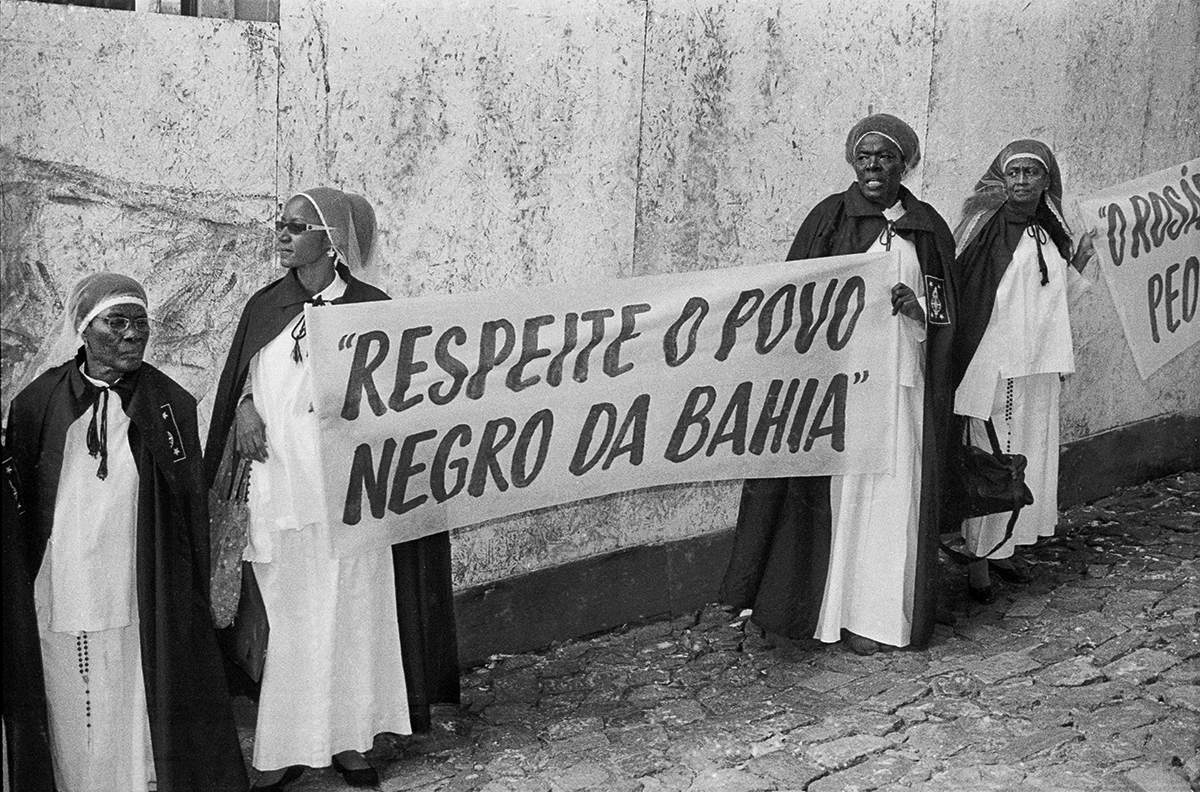

CAPTIONS p. 143: Model in the Black Consciousness Week at Odorico Tavares State School, Feira de Santana (BA), 1998. p. 145: Photo studio for the Black Cards series: postcards with Black subjects, Salvador, 1993. p. 147: Black Cards series: postcards with Black subjects, Salvador, 1993. p. 148: Estética Negra [Black Aesthetics] series: Afro hairstyle show at the Black Consciousness Week at the Parque School (Carneiro Ribeiro Education Center), in the Pero Vaz neighborhood, Salvador, 1991. p. 149: Estética Negra [Black Aesthetics] series: Afro hairstyle show at the Black Consciousness Week at Parque School (Carneiro Ribeiro Education Center), in the Pero Vaz neighborhood, Salvador, 1991. p. 151: Estética Negra [Black Aesthetics] series: combing the Black Power hairstyle in a hairdressers in the Retiro neighborhood, Salvador, 1994. p. 153: Candomblé adept asking for alms for São Roque [Saint Roch] in the Federação neighborhood, Salvador, 2013. p. 155: Cesteiro [basket seller] from the Praia Grande Quilombo in Ilha de Maré, selling baskets at the São Joaquim market, Salvador, 1992. pp. 156-57: Porters at the São Joaquim market, Salvador, 1992. The hats were used to protect the head from the load. p. 159: Seasoning seller at the São Joaquim market, Salvador, 1992. pp. 160- 61: Afro Olodum block Carnival parade, with the theme “The Treasures of Tutankhamun”, in the Largo do Pelourinho, Salvador, 1993. p. 163: Candomblé adept asking for alms for São Lázaro [Saint Lazarus] in the São Joaquim market, Salvador, 2008. pp. 164-65: Protest by the Sisterhood of the Church of Our Lady of the Rosary of the Blacks, in the Largo do Pelourinho, July 2nd, Bahia Independence Day, Salvador, 2012. p. 167: Young man working as cordeiro [rope man], a temporary job during Carnival for Black people to hold the Carnival blocks’ ropes so the white people can have fun, Salvador, 1992.

Tags: Arquivos fotográficos, Fotografia Afro Brasileira, Fotografia baiana