Fernando Lemos: A surrealist in Brazil

Publicado em: 2 de October de 2019Fernando, your best known photos were taken when you were between 23 and 26 years old and lived in Lisbon, under António de Oliveira Salazar’s New State (1933-74). How did your artistic career start?

I was drawn to the world of art by chance, or better, by some circumstances of life. I learned to read very early, and from an early age was always writing and drawing on my school friends’ notebooks. At home, I helped my father in his carpentry shop, working with wood and designing small pieces of furniture. I learned the technique of lithography, and after that painting and drawing. This persistence has helped me to overcome the deficiency of paralysis: I felt that I should do everything that the other boys did, and a bit more. I went to the school of industrial design, where teachers helped me to improve my drawing and my writing. Later, the connection that developed between the surrealist movement and the automatic writing technique made me realize that there was room for my way of doing and thinking.

When did photography emerge as a form of expression for you?

When I was between 18 and 19, I had the opportunity to spend some time in the Berlengas Islands, off the west coast of Portugal, a historical place that had been a prison and housed the monastery Misericórdia da Berlenga. At that time, it was almost abandoned. It was a place of refuge for fishermen when they needed to shelter from storms, where the only inhabitants were an old couple, who made food for me and my friend Marcelino Vespeira. We liked the place precisely because there was no one living there to bother, and it was ideal for us to carry out our experiments in oil painting. In a way, oil painting led me to photography. It was there that I realized that the sea and the water acted as a lens, in an accumulation of transparencies, and had the insight into the nature of photography and its potential for transparency. As with painting, automatic writing and dreams, photography is a form of transparency of the unconscious, of revelation. In the centre of it all, was, for me, the phenomenon of concealment. So it was not just the strength of desire but a necessity, and I decided to buy a camera as soon as we returned to Lisbon.

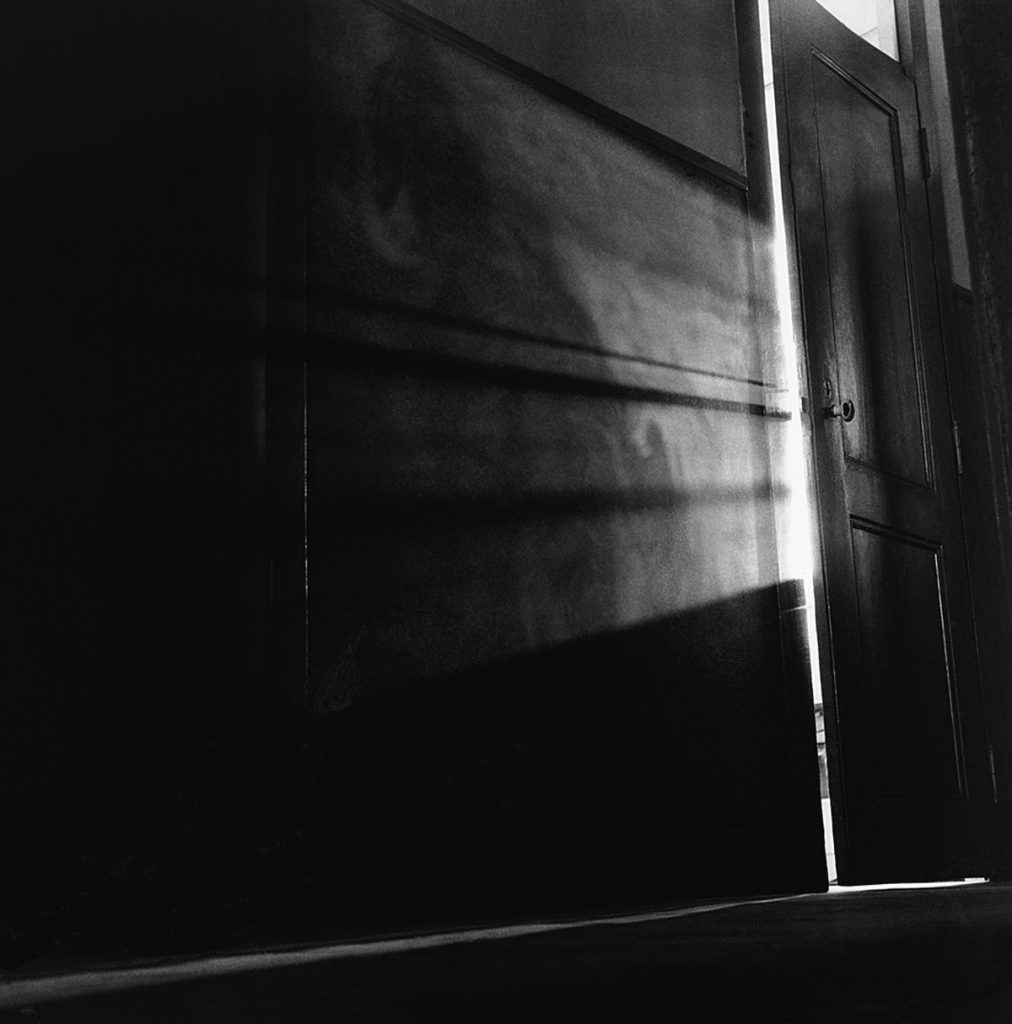

The day after I bought the camera, I took my first photo: a view from the window of my room – of Rua do Sol ao Rato – in which you can see part of the street where I was born at the left hand corner of the image. I became the only artist amongst the Portuguese surrealists who used photography – my colleagues made collages, paintings. I found a direction for my photography, taking portraits of prominent intellectuals, my talented friends who, because of the political repression, were little known in Portugal.

Where did the young Lemos get to know Marcelino Vespeira and the surrealists?

I already knew the surrealists, I knew them from school, bars, cafés. In Portugal, as well as in Europe, the intellectuals met in cafés, bringing their typewriters and working all day. There was a café where the surrealists, people connected to the Communist Party and the neorealists met – the Café Brasileiro. I started meeting all these people, mixing with them. I took portraits of Mário Cesariny, the greatest Portuguese surrealist poet, and of the poet and writer António Pedro, who had met André Breton and Benjamin Péret in Paris. Our group was strongly connected to Breton, but then we turned away from him, because he demanded that we distance ourselves from the neorealists and the communists. We responded negatively, because in Portugal, at that moment, we were all against Salazar. We met in the café and in places where there were debates and lectures, such as the National Society of Fine Arts.

We hated all that formality and participated just to annoy people. Once we went to a lecture by the conservative critic João Gaspar Simões, who hated the surrealists, planning to cause a scandal. Without him knowing, we stole his lecture notes from his coat pocket. He only realized this when he went onto the stage. When he started to speak, we chanted, parodying the Portuguese anthem: “Against Gaspar Simões…” Everyone laughed, there was an uproar. We wanted to demoralize the structures of the fine arts system.

In 1952, you, Vespeira and the painter Fernando Azevedo organized a collective exhibition at Casa Jalco in tribute to the poet and writer António Pedro.

It was the first time we made our mark in the visual arts world. The exhibition took place at the Casa Jalco, a shop selling furniture and decor in Chiado, one of the best neighborhoods in Lisbon, near the Fine Arts College. Students, who passed by, spat, tore things, insulted us, simply because they disagreed with our surrealist manifestations. Fifteen days later, when the exhibition finished, we hired a flat-bed truck, put everything on it, climbed on top of it and wound a banner, in big letters: go home, stay calm, burgeois. We were booed a lot on the way. Everything happened to us, even police harassment.

Another surrealist group, more into drugs, got friendly with the bullfighters. These people were very special, and we also loved bullfighting, which helped us get close to them. They threw parties dedicated to our group and collaborated with the general upheaval which we sought. My involvement with the art world came through this series of coincidences, of political and social circumstances. In spite of everything, Portuguese society allowed these marginal breaches.

Without Surrealism, it would not have been possible to challenge and question the conservatism of the dictatorship. I ended up dedicating myself to photography in part because of the surrealist impulse to add to the reality what one lacks, to have a passion for things that happen for their own sake, to give strength to reality, add hatred, coincidences, codes to things that do not yet have a truth. In a way, we were cursing ourselves. It was a space that we sought, in which there was some mistake, a form of controlled freedom that we, artists of the time, could not tolerate any more.

How much did you know about photography at the time?

Very little. When I bought my Flexaret 6×6, I started getting information about it in manuals and magazines. No teachers, much less going to exhibitions for comparison. My approach to photography was slow. I began to see a photograph in everything, guiding myself by poetry and literature. As everything needed an image, I chose photography to do it. When I read, I feel that there is an image there somewhere, as if seeing a landscape. It is a way of seeing, and not just a raw material that is there. That is why I started to give a lot of importance to literature, especially fiction, to the essay and everything that needs an image. For us, photographers, the great poetic images have something of photography about them.

But the photograph is not, in this context, something necessarily descriptive, is it?

No, it is the thing in itself, often temporary. When the poet says “piano”, it does not mean “a piano”. The image is temporary. Reading a lot has taught me to see the wide territory that is photography: seeing a Henri Cartier- Bresson is a way of reading.

Listening is also important for me. Seeing is a form of listening, and photography, as with poetry, should be listened to. Guernica, by Picasso, or Goya’s work should also be listened to. It is always a way to listen to the other. It is not just the eye, but a wider perception. The sound of a drum was the first form of human communication. The drum was the photography of the time; the sound was the image.

Were you interested in the technical side of photography, in the photographic process?

I am a primitive in relation to technology in general. I had a dark room at the studio, but soon gave up the process, when I realized that it was a matter of working at times that were not my own. The technique takes time and it takes a lot of work. In addition, I spoiled a lot of material. My way of thinking was associated with the act of photographing, painting, writing. When I write, I sense the images.

Many of your portraits create multiple views of the same person. Did you plan them like this?

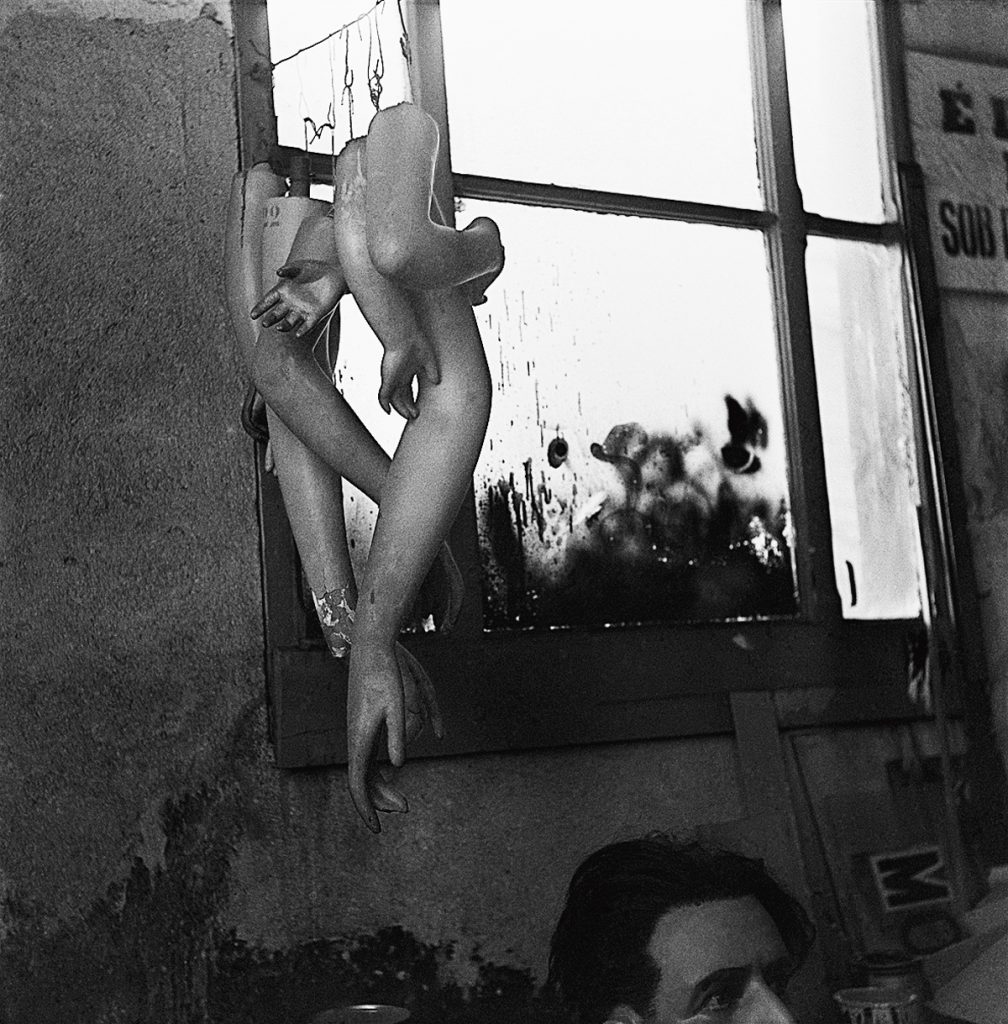

Yes. Overlays were more used in photography when I realized the richness in transparency that came from placing one negative upon another. In my photography, particularly in the portraits, I worked by overlaying two layers of images. When you photograph a person, we are not photographing something fixed, a mask. After all, in a split second everything changes. We change our expression from moment to moment, suddenly, several times. So the portrait should be multiple, to give more life to the image. We are not a mask. As I reflected on this question, it seemed logical that it was all one thing. The layer to me is an overlay, a transparency over another. The uniqueness of my work is in the use that I make of light to destroy an image with another.

I have always been political, ideological and aesthetically connected to those around me. I never photographed people I did not know. We were in our country, but confined in the darkness. My friends were affectionate accomplices; all posed granting the same aesthetic freedom to me, committed as they were to experimental Surrealism and poetic invention, an affront to the conservatives on duty. The intent behind the portraits was to reveal the face of Portugal through these smart people, these banned artists, discover the face that we Portuguese had at that somber time.

Cinema is perhaps the world’s self-portrait, but it is not ours, it’s not our thing. The idea that concerned me then was to put together all those experiences and show the non-mask, the non-thing. A person who suffers does not always show a mask of suffering. At most, I was writing a text, putting together a description of each of those friends who lived with us in those days. A description is a photograph.

Was there something of a performance about the portraits?

Yes, and no. There is a sign of expectation. One pose is always waiting for another; the gesture I make now is waiting for another. There are no free gestures.

In the 1940s, you went to Paris. How were your meetings with the Portuguese-French painter Maria Helena Vieira da Silva and with Man Ray?

I met Maria Helena in Paris, when she was married to the painter Árpád Szenes, soon after she left Portugal. I spent some time at her house/studio, where she would regularly welcome artists, conductors, writers, painters. I met a lot of people at these meetings and used the opportunity to take portraits of her and some of the guests.

I was with Man Ray on the eve of his exhibition of watercolors at Gallery Berggruen, in 1951. I believe that was the first of the post-war period. That was when I also met Paulo Emílio Sales Gomes. One afternoon when we were visiting many of the city’s film clubs, Paulo Emílio introduced me to the surrealist poet Benjamin Péret, the theoretician and film critic André Bazin and to the Portuguese art historian José-Augusto França, among others.

Did you photograph Man Ray?

I was familiar with his work, but did not know him personally. I only had a superficial knowledge of his photographs, as Portugal was isolated from the vanguard, precisely because of the dictatorship. On one of my visits to Maria Helena’s, we exchanged our cameras, but the portrait did not happen. Today it is only a good memory. At that time, my strongest references came from Marcel Duchamp and the German expressionist Max Ernst.

How did you come to live in Brazil?

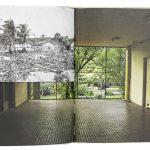

After all these experiences, at about the age of 20, I decided that I could no longer be confined to that place. I arrived in Rio de Janeiro during Carnival in 1953, soon after publishing Teclado universal in Cadernos de Poesia magazine in Lisbon. The Portuguese decorator and set designer Eduardo Anahory, an acquaintance, lived in the city and I brought with me letters of recommendation to Manuel Bandeira and Carlos Drummond de Andrade. Besides, I had met Paulo Emílio Sales Gomes in Paris. The impact of the change was huge, as I had left my country because of a dictatorship which strongly repressed freedom of expression. I soon found somewhere to live in Rio, in Santa Teresa, but in November the same year I moved permanently to São Paulo to work on the city’s celebrations of its 400th anniversary, in 1954. I made an abstract panel – 15m x 5m – for the entrance to Oca in Ibirapuera Park, on the theme of the city which was born wild and evoluted until it became civilized. Twenty years later, the mural was destroyed, without anyone letting me know.

What is the last memory you have of Portugal and the first of Brazil?

My experience in Portugal was linked to the Communist Party, of which I never became a member. There, I was always confined to the offices, never on the street, as I would like. I couldn’t put up posters, go leafleting, face off against the police, as I still had some problems related to the polio I had had as a child. I limped, and many friends were killed doing those things. Faced with this difficulty, I wanted to do more, but I didn’t want to be better than the other comrades. I wanted to do things as if I was healthy.

I arrived with no money, no job, nothing, just some fantastic contacts. I felt I was the same young man from Portugal, going through difficult times here just as I did there. But I was somewhere new. At least until 1964 [the year the civil-militar dictatorship began in Brazil], one could breathe very well here. My youth had been stolen by the dictatorship, but here I was another man. Brazilian people treated me differently, and this gave me a certain importance. Everything was lighter, more enjoyable. The journalist Flávio de Aquino introduced me as an illustrator to the Manchete magazine, and in April 1953 I started working there as an illustrator, alongside Lúcio Rangel, Paulo Mendes Campos and others. I also worked daily for some twenty years as an illustrator for the literary supplement of the newspaper O Estado de S. Paulo.

How did the opportunity to have the first exhibition of your photographs in Brazil come about?

I exhibited with Eduardo Anahory. I showed the photographs which I had brought with me, the works were ready and easy to display. Paradoxically, the photographs were quite successful and were well received by the artists and critics of the time. The images brought a certain freshness which adapted well to the Brazilian modernity. And, of course, the task was made easier by the contacts and friendships I had rapidly made here. Sérgio Buarque de Holanda, Rubem Braga, Antonio Candido, Sérgio Milliet (introduced to me by Paulo Emílio) and Regina Katz. In August 1953, I exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art of São Paulo (MAM), thanks to a recommendation by Paulo Emílio to Sérgio Milliet. And then, in November, I exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art of Rio de Janeiro, with the introduction by Manuel Bandeira.

Do you think you were befriended by the Brazilian cultural elite because you were a left-wing exile from the Salazar dictatorship?

I don’t know how to explain it, but I was recognized for my skills as a photographer, illustrator and painter, and I found my position in the arts world. I also got involved in politics through the Portuguese and Spanish anarchists living in Brazil. The 1950s were a very fertile period in Brazil in the cultural and political area, in particular in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro.

Here, you stopped photographing and started some business ventures, such as the Giroflé Publishing House. How did that come about?

Giroflé was set up to be an independent publisher of children’s books, something still in its early days in Brazil at that time. I gave it the name giroflé from an old Portuguese schoolyard rhyme [he chants “giroflé, giroflá”]. In 1961, I got together with Sidónio Muralha – an old friend, a great Portuguese neorealist poet, communist and, ironically, the director of Unilever in the former Belgium Congo – and another intellectual, Fernando Correia da Silva, all of us Portuguese, and we set up the publishing house after interminable meetings and discussions. We established the company as a cooperative and many intellectuals and businessmen with links to culture joined. The businessman Leon Feffer, for example, believed in the project and gave us all the paper for the first books we published. We published many writers who had never had the opportunity to write for children. We also tried to get Paulo Emílio, Cecília Meireles, Carlos Drummond de Andrade and Vinicius de Moraes, who volunteered to create the Dicionário da travessura [pranks and mis- chief dictionary], which unfortunately has never been published.

A lot of people signed up for it. We set up an office in a building designed by Paulo Mendes da Rocha on Baronesa de Itu street, furnishing it with furniture from Forma. Artists and writers such as Fanny Abramovich, Willys de Castro, and Aldemir Martins came on board as collaborators. Darcy Ribeiro was so excited with the project that he ordered our books for the Instituto do Livro [Book Institute] in Brasília, which never came to pass. We even produced a collection of postcards with drawings by children which we selected from public schools in the city, and the resulting income was donated to the school itself. They were idealistic projects, big ideas that had a short life. Following the military coup of 1964, the projects were abandoned, one by one. Two years later, the dream ended before it had a chance to become real.

And soon after, you set up the design studio Maitiry?

Maitiry was born in 1965, soon after several photographers and journalists were dismissed by the magazine O Cruzeiro, owned by Diários Associados. Some of our collaborators, for instance the photographers George Torok, Luiz Autuori, Paulo Namorado and the journalist Audálio Dantas, came from the magazine, and we also had Aldemir Martins, the photographer Jorge Bodanzky and the poet and designer Décio Pignatari. The idea was to build a creation studio for both fashion and design, as well as multimedia projections (then still using slides), embryonic initiatives that already required a multidisciplinary work team.

Did the graphic arts become your main area of expertise?

Yes. My first course at the School of Decorative Arts in Lisbon was on lithography. I have always worked with the graphic arts. At Maitiry, I created and developed logos and packaging, far from the advertising area. I am against advertising. I connected to the creation of signs, to everything that man produces for man himself. Industrial de- sign takes the product to man; advertising is made to seduce and convince the consumer. I did everything in this area: wine labels, fabric prints, book covers, an infinity. I consider myself a graphic designer. It has something of crafts, which has fascinated me since my first experiences with my father in the carpentry shop.

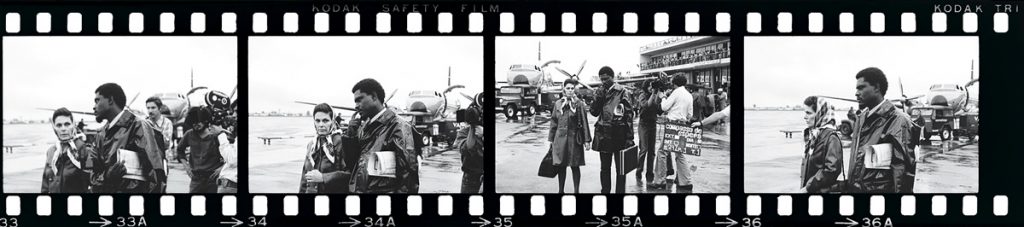

In a way, you only returned to photography with the film Compasso de espera [setback] (1973), directed by Antunes Filho. How was the experience?

Antunes was one of the few people who saw my show at MAM São Paulo, which at the time was still on Sete de Abril street. The museums rarely had photographic exhibitions at that time. Antunes showed me the script and gave me no option but to be the director of photography. “I want your photography in my film,” he said. I was very embarrassed, because, despite it being a wonderful invitation, I had no experience whatsoever with the film camera. I replied saying that I could not be the director of photography, because I lacked experience, but that it would be a pleasure to do the aesthetic direction of the photography. He insisted, and, given the impasse, I went in search of Jorge Bodanzky, who had just arrived from Germany and was working with me at Maitiry. Bodanzky ended up doing the direction of photography, and I took the scene and publicity photos. I did not have a direct involvement in the design of the photography for the film, but I remember that several scenes were redone with the intention of placing the actors with their backs to the camera, because Antunes wanted to highlight the shadows lost on the screen and the crossed lines of the characters on those shadows. The idea was that the film had little pretention to be an art film, but that the images should flow smoothly, naturally. I did not look for sophisticated angles or framing, just dense portraits of the characters. It was a well-behaved movie, but very well done.

During this time, the photographic work you did in Portugal was set aside. How did you restart it?

It was a gradual process, without me fully realizing it. In 1977, I participated in the collective show A fotografia na arte moderna portuguesa [Photography in Portuguese modern art], held at the Center of Contemporary Art, in the city of Porto. Then, in 1982, Lisbon decided to organize a major exhibition at the National Society of Fine Arts about the dark years in Portugal, the decade of the 1940s, when the Salazar regime stepped up its surveillance and strengthened its ideology. The show, called Refotos dos anos 40 [rephotographs of the 40s] brought together for the first time a generation of artists almost unknown in the country. This is because this group was against the government: they could not work, could not give lessons, could not publish. The pictures that I took became a gallery of important figures who at that time could not do anything themselves. It was not only art, it was a anti-fascist, anti- salazar struggle, which claimed the lives of many. In the early 1990s, the photographer Jorge Molder, at the time the director of the Center of Modern Art of the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, sought me out because he wanted a better look at my photographic work, which he knew only superficially. The Director General of the Foundation thought that it was urgent to make a book about my work. Molder invited me to go to Lisbon. I organized my negatives and off I went with all the material, which impressed him. He referred me to the largest photographic laboratory of France, the Chambre Claire, which was also delighted with the photos. In November 1990, the Gulbenkian Foundation organized my first big show, during the Paris Month of Photography.

After the Month of Photography, another exhibition, À sombra da luz [under the shade of light], opened at the José de Azeredo Perdigão Modern Art Center in 1994, the year in which Lisbon was the European Capital of Culture. It was a success. After this, I received more invitations: Madrid, Porto, where in 2000 I received the National Photography Award from the Portuguese Photography Center, directed by Tereza Siza; then Aix-en-Provence, at the international congress of Portuguese and French writers; Frankfurt, in the International Book Fair; Moscow; Barcelona.

That was a lot of exhibitions over a short time. Which one was the most striking to you?

All were important, but the exhibition in Moscow in 2008 was different. The Russian curator Olga Sviblova asked the Camões Institute and the Gulbenkian Foundation to choose me to be the Portuguese photographer invited to the 7th International Photography Bienal. Imagine me, Fernando Lemos, representing Portugal almost sixty years afterwards at an international photography exhibition with works I had done in the middle of the Salazar dictatorship. What a glory!

How has it been, looking back again at your photographic work and rediscovering old companions 40 years later?

There was a hope in new things. Today there is much talk of young artists, and I wonder what will happen with them 40 years from now. I came to the conclusion that I should celebrate the entry of young artists and critics into the visual arts world, because they are the ones who are now looking at my previous work. And they are the ones who are surprised and say: it seems that it was made today. It has become clear that the photography was out of the ordinary. You won’t find a car or any other reference to the period in my photographs. That never interested me. In fact, they are intended to be timeless, because they come from strangeness, a new world that needed images. I had in me an intellect and a memory that needed images. I still feel that power, that shows how I was on fire, open to the new. The discovery of photography was for me not an end in itself, but the beginning of my quest for the strange. At the time, there were many poets, artists, writers and politicians who we liked, but only one or two photographers, who I discovered later. At that moment I was a sign of hope, which explains the letters of recommendation that brought me to Brazil.

How was it organizing the exhibition O real como enigma [the real as enigma] (2016) in São Paulo and what was the reaction of the public?

Drawing has occupied most of my time. I draw what is invisible on white paper, trying to show how each stage of my drawing reveals it: it starts by taking a stance, then grows like a building, gaining volume, it becomes a more cubist thing, until it turns into a kind of palimpsest. The drawings reveal what was inside the blank paper. That is what I created for this exhibition: a small drawing, like a mystery, which is then scanned and expanded as if it were a photograph. The drawings, which I do first thing in the morning, are free and automatic, coming from the dreams of the previous night. Each scene gives an impression of being able to be explained, but they are revealed as surprising and inexplicable. This effect of uncovering something in the drawing ends up turning into my secret. The procedures applied in developing this work create new syntaxes that deserve attention. This work is more conceptual; it demands more reflexion. What is represented is the result of a dream. No-one published a critique of the exhibition. If that is all or nothing, nobody wanted to know.

Have you been dreaming a lot?

I have for some time been experiencing these incredible nightmares, that I began to note down, to analyse and keep. I have gone through several phases, and today I am able to have nightmares that are focused on a few themes, recurrent places and things. Upon waking up, I realize that that image had already been with me for some time. I have some control over it, which does not stop them from being very short instants, of a few seconds, into which are concentrated more than 60 years of my life. This is terrible, including psychologically. Therefore, I am ready for anything, including madness. Some phases are more painful.

We have two types of humanity: one half of humanity that keeps trying to be more than it is; and the other half which is depressed, those who cannot suffer any more. I am now in a phase where I am recovering. I am not who I used to think I was. I started to review relations which I had cut without any reason. These people no longer have me as a reference, because they did not feel something positive in return. I started a period when I wanted to know exactly what my faults are. Since I was a child, I realized that, despite my disability, I had to do something, not to be better than anyone, but to show that I too was capable of doing something. This has helped me.

Now I am starting to feel an impact from the smallest things. I dream that I am in my street in Lisbon – I dream a lot about Lisbon –, and I dream of crowds of people, all with the same face and the same clothes. This is permanent. I walk up my street, I feel some difficulty with my left leg, the cane does not help, and I stop at a building. There is a hospital on the corner, and I can’t move. People who pass by don’t even look at me, I feel that I’m lost. “You’re already nothing. You’ve already died.” Then I wake up, and nothing seems funny. My psyche is part of my conception of work; I have to understand which is the reason for hiding things, the mysteries, this strangeness in the hundreds of drawings that I make. Humanity is a pain; if there is someone who feels it, it is the artist.

Do you create sleeping and execute awake?

Now we know that our life is divided into two parts: half asleep, half awake. The important time is when we are sleeping, when we dream, because the dream does not hide anything and brings the infinite. Being awake is the other part of the day. The part of the day when living is working. This question is latent at work. When we are awake, we do everything that we imagine. Things look for us. It is a mistake to think that we go after them: they are the ones who come after us. Photography is also something that mankind looked for, but in fact it was photography that came looking for us.

Do you believe that there is a relationship between dreams and automatic writing?

Automatic writing seeks that which is exactly the opposite of automated machinery, as the camera of good behaviour. With photography, for example, I always disrespected standards and applied some of the strategies of Surrealism – full creative freedom, the overlap of images from different light and shadow registers, and the automatism of a disobedient camera. I always sought to reveal the invisible. I have always tried to create images that brought to the surface my reflections on revealing the hidden. The only thing that interested me about the surrealist group for which I was the photographer, indeed, was the question of revealing the hidden.

In the beginning, I would take a printed sheet from a newspaper or magazine and, later, with India ink, gouache and a cotton swab, apply a random shadow until an empty space was revealed. This principle of concealing, of occulting, which has nothing to do with the occult, was a great learning experience, a procedure that has guided my whole creative life in photography, in writing and in drawing. I only became interested in Surrealism because the dream was the only territory in which there was nothing hidden. The dream was to reveal, to arouse interest, not to hide. The photograph is the moment of revealing. All our artistic actions are unconcealment, i.e., seeking what does not exist, that which is invisible, in the form of a palimpsest.

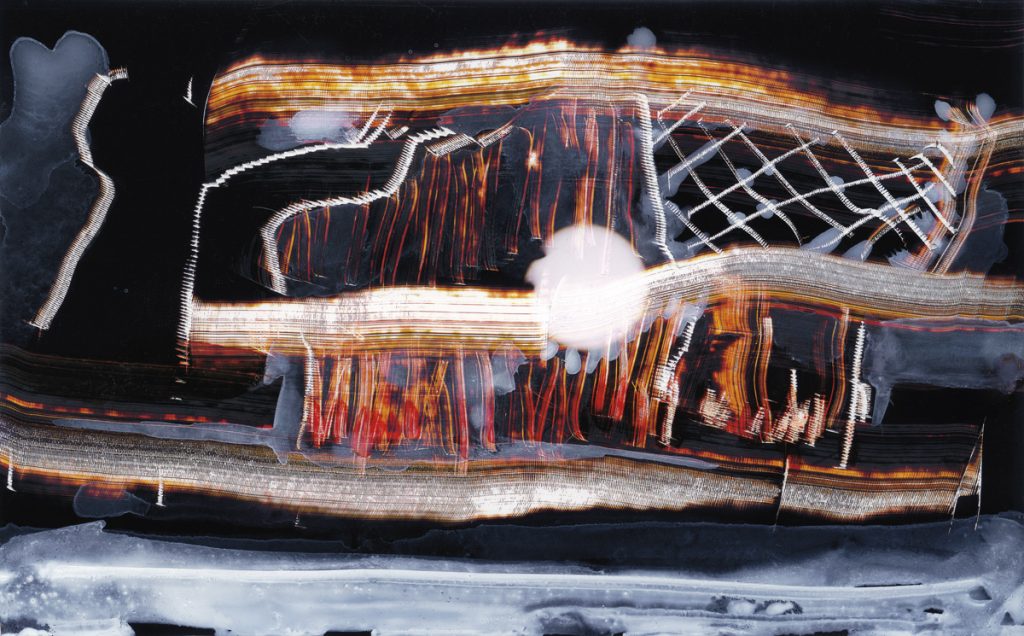

Do these thoughts also apply to the series Ex-fotos, which you showed in 2014?

This is an important work for the thesis that I have defended about revelations. The work is also associated with the idea of palimpsest. A search into language, into one art within another. In this series, it all came about almost by accident: I realized that the discarded amateur snaps made by friends who were enthusiastic about photography and which I had been collecting for some time, called out for interventions. The surrealist experience of concealment showed that it was possible to intervene in any image from a newspaper or magazine, and find something in it. Here the procedure was the same: intervention with a cotton swab or India ink in photos and the creation of a sort of hole. I was looking for something concealed to be able to reveal it. What was hidden in that hole?

I took those copies which I first called “rejects”, and started to play with the pun ex-vows, because it was something connected to the belief in desire, taking into account that desire is the cure for what we lack. I started the project with the goal of hiding and revealing things, sometimes scraping with a razor blade or steel wool, sometimes adding some water. Colors that I never imagined could be there appeared. I made a portfolio and took it to Lisbon. The curator of the Vieira da Silva Museum exhibited them and published a book.

How do you relate these two moments in your photographic work, the one in Lisbon and the Ex-fotos? Is there a common vision of what photography is?

I use the same procedure, bringing the invisible to the surface of the image and revealing what was pulsing in there. My photography is the result of the visual culture that I have acquired throughout my life. I use all my memories: a scene from a film or play, a cathedral, a piece of tapestry. Photographing is a hope. An analogue form of thinking. A photograph is not a whim or an invention of the moment. It is the scientific result of a desire to reveal things. Seeking the truth is a form of revealing falsehood, and photography is part of this craving for revelation. The importance of photography is memory. It is the revealer of truth and falsehood, of what is hidden.

I have always sought the strangeness. In the case of photographs, everything that is there was not put there by me. My photography is the revelation of the dream. The attraction of photography is to have and seek, in the aesthetic sense of art, the strength of a dialogue. Art is a form of permanent dialogue with the unknown. At the limit, you have to imagine that, to enjoy a thing, it also likes you. The veracity of a picture increasingly seems to me to be a latent power, irresistible. We are the interpreters of everything and wise about nothing. Nothing seeks us, a picture calls us. We have to be attracted to establish this dialogue. The dialogue is an enigma. Photography can be a chance, an appearance. It is as if it were something new and strange.

These reflections have emerged at a time when I adopted photography as language and expression, in those first experiences with oil paints and water on the Berlengas Islands. The water and the transparency offered me an understanding of the invisible. The eye, like the ocean, is an accumulation of transparencies – if we cut a slice of the ocean, the result is a lens. The optical degrees are exactly the sequence of accumulations of transparencies. The lens is an extension of the eyes, as the hammer is an extension of the hand. The lens is the dis- covery of space; it cancels the distances. Man needed the lens and reached the satellite, which, of course, has another scale.

By distancing and closing in, the lens is responsible for revealing. At that time, painting was for me a liquid experience, near to that of the watercolor, something less thick and less extensive, which made me realize that it didn’t have the importance of black and white, the accumulation of light and dark offered by the analogue photography of that moment. All this coincided with my ideas. The relationship between concealment and transparency, black and white, is my principle in photography and the foundation of my visual theme.

You have established a relationship between the fish and the photograph countless times. What did you want to say?

This is also linked to the question of the sea and of transparencies. When I worked in the darkroom, I fished for the image in the chemical trays. For me, the image that came out of the developing trays had life, texture, personality, like the fish that we are catching. I had a good experience in Japan in 1977. There, the fisherman removes the fish from the water, takes it to the market, wipes it in black ink and then prints it, so to speak, using a piece of rice paper, creating a copy. This copy was pinned to his door with the price of the fish. All of this is communication.

The writer José Saramago, referring to your work in 2001, used the word “appearance”. Is it possible to establish any relationship between appearance and revealing?

Appearance refers exactly to revealing, which, in the poetic sense, is above all strangeness. If the image was not strange, it could die in itself. Everything that is new seems strange to us. This is the main idea behind my artistic work. The transparency of the lens and the photographic process itself is an appearance of things which are hidden or are invented. Max Ernst used to say: “We see more when the eyes are closed.” Therefore, the blind person is the true artist. The blind person is the one who invents everything that they cannot see, they are the great seer. We can classify the various types of blind person: he who does not know what he sees and then invents it; he who has imagination and thinks they know what they see; and he who does not have the slightest idea of what he really needs to see. This interests me as an artist. Simply put yourself in the place of a blind person to realize this.

Should the artist have a discourse about their work for their art to come to life?

I find it difficult to discuss this. It might be more worthwhile thinking about the meaning and the validity of the work. It is indisputable that art should be assumed as an object that will always have some validity, because there are also free gestures in art. But it is up to us, artists, to know where we want to get. Today, photographers are almost all the same. Photography is becoming a mannerism. On the other hand, what happens in the world obliges us to think all the time, even outside of art.

You said once that contemporary photogra- phy, in the face of so much sameness and repetition, is a graveyard. That it is not memory, it is forgetfulness. How do you see this?

I often say that photography has gone from mirage to execution. In the same way as architecture becomes over time a remembrance, the skeleton of a time that has passed, the photo also has moments where its usefulness is to awaken concern. The images are accurate, but they represent something that we already do not recognize. It is a time that is not ours, but it is there. This is intriguing, but, at the same time, could this not be death, in the sense of extinction? We know that photography is an art, eternal from the form of its birth. Photography is born with its own record and eternity.

What seizes us is to feel that we are part of that eternity. We are born with it as a rich, visual wand. It is our great revenge on death, because we know that there is nothing, nothing at all, better than life. Everything we do in life is more important than death. So photography is a revenge, a way for us to impose ourselves on the world, and at the same time a defence, a form of solitude and of taking care of loneliness. When we see a photograph, we have awakened something that was lonely. Loneliness is a narrative. Photojournalists and war photographers are the kind of photographers who offer us this loneliness. Loneliness is a trench, and is perhaps the only language capable of facing death itself. The vision gives us our presence in life.

Vilém Flusser used to say that, when we die, the photographs will remain, and that they prolong and intensify our existence in the lives of others. Do you agree?

Of course. Flusser also argues that memory is as important as forgetfulness, because our first great strength, the first great energy that we acquire, is intelligence. Intelligence as a defence and as an attack, with sufficient freedom to defend ourselves from other intelligences which want to dominate us. Intelligence includes the ordering of the world by the look. Why is the mother our first important muse? What is the first landscape that a child sees? The look!

Having worked in so many fields, do you consider yourself to be a photographer?

I reply: I am photography. The Catalan artist Joan Fontcuberta says: “I feel photography.” I like this statement because it sums up what I think about photography. Photography gives force to all that you are. Today we live with technologies that are dangerous because they rush through life. People, even with nothing to do, are always rushing.

You say that you like to photograph as if you were painting, write as if you were drawing, paint as if you were photographing.

This is the principle of automatic writing. Releasing the unconscious and letting it free. I start to write without registering any idea, I leave the writing to develop freely. Today I use this system in practically everything. I don’t approach drawing, for example, with a preconceived idea; things appear by themselves. You can have an intuition of blindness, a form of imagination which belongs to the invisible. You can be a knower of the unseen.

The experience of photography is a bit of this. We make visible what remains invisible there. The invisible is a power, a possession, a way of being. Then all this philosophy seems to me that it is for the artist to introduce a bit of fantasy, this thing that is not as inventive as well. When I see an image, when I see that it is already a photograph, then I will not photograph it. It feels embarrassing to copy it; I have the impression that it is already confirmed as a photograph. This means to say that the photograph was made before we took it. It is in nature, and nature brought the photo looking for us. It has become a science that seeks us out. It is like the question of memory. Memory also went after the photograph, just because it needed the image. This is the great potential of photography, it is the affirmation, the evidence of things. ///

+

Fernando Lemos: O real como enigma (Galeria Milan, 2016); Eu sou fotografia: Fernando Lemos (Fundação Cupertino de Miranda, 2011); Fernando Lemos, atrás da imagem (2006), a documentary by Guilherme Coelho