Everyday life on the hill

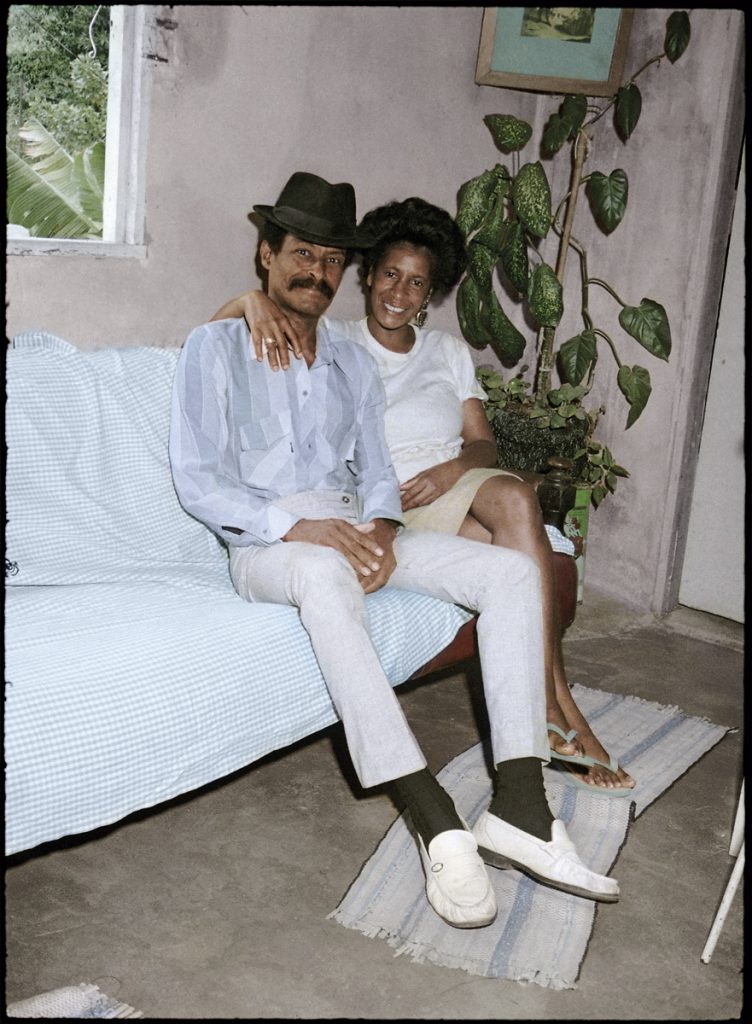

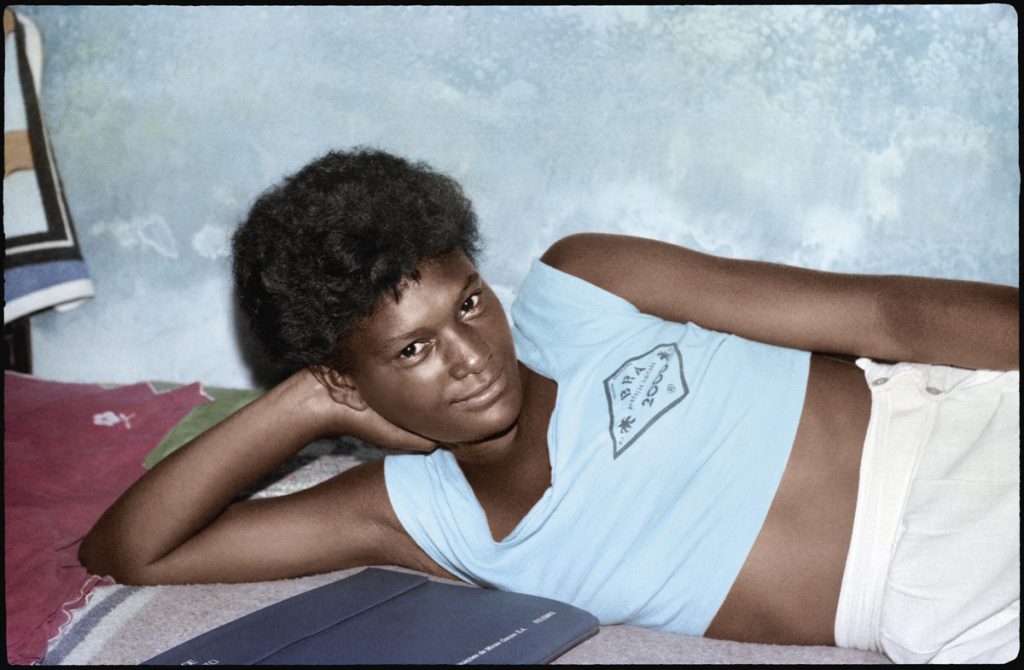

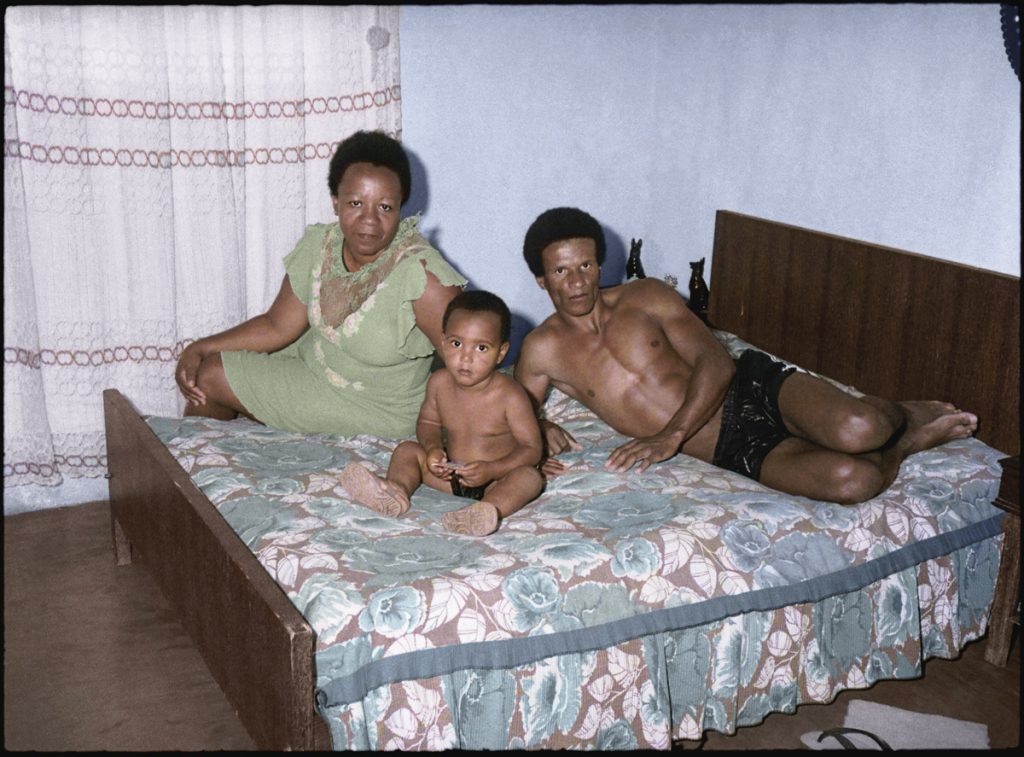

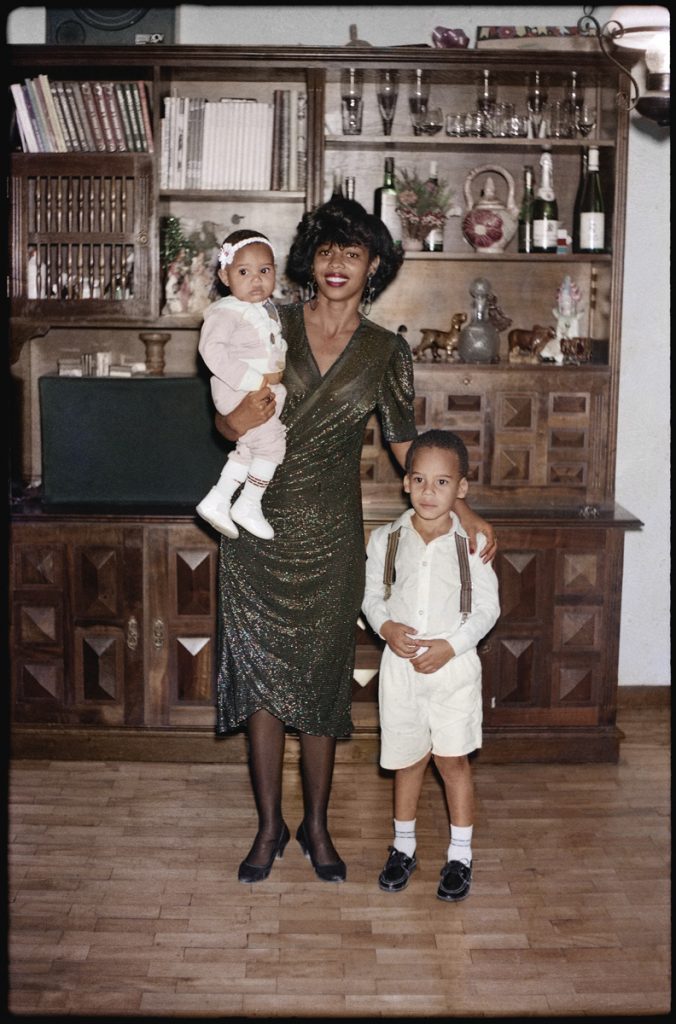

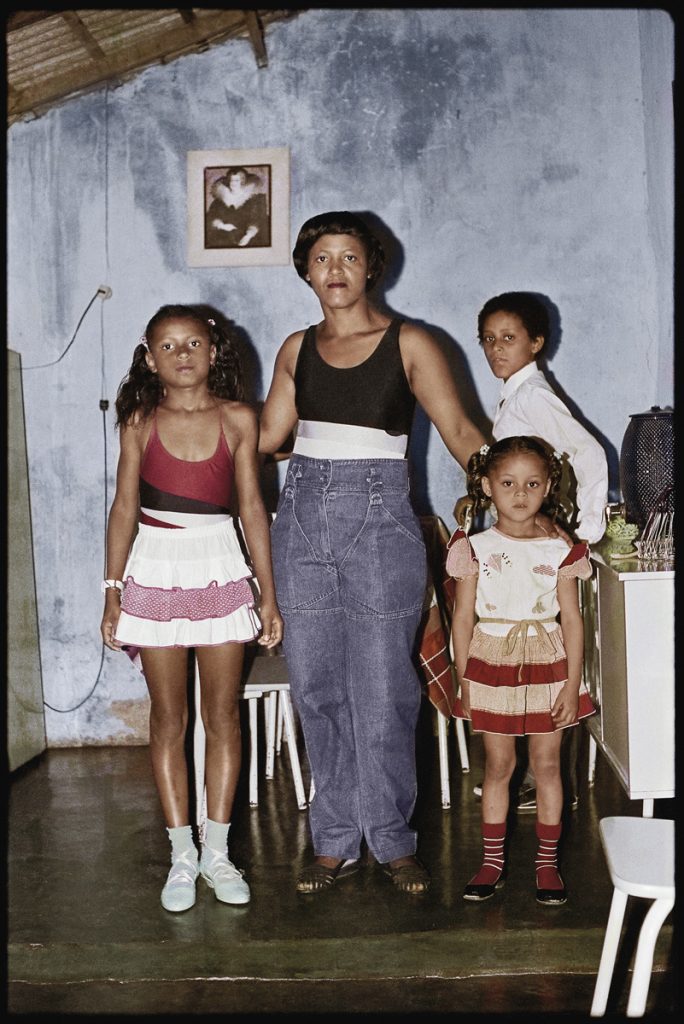

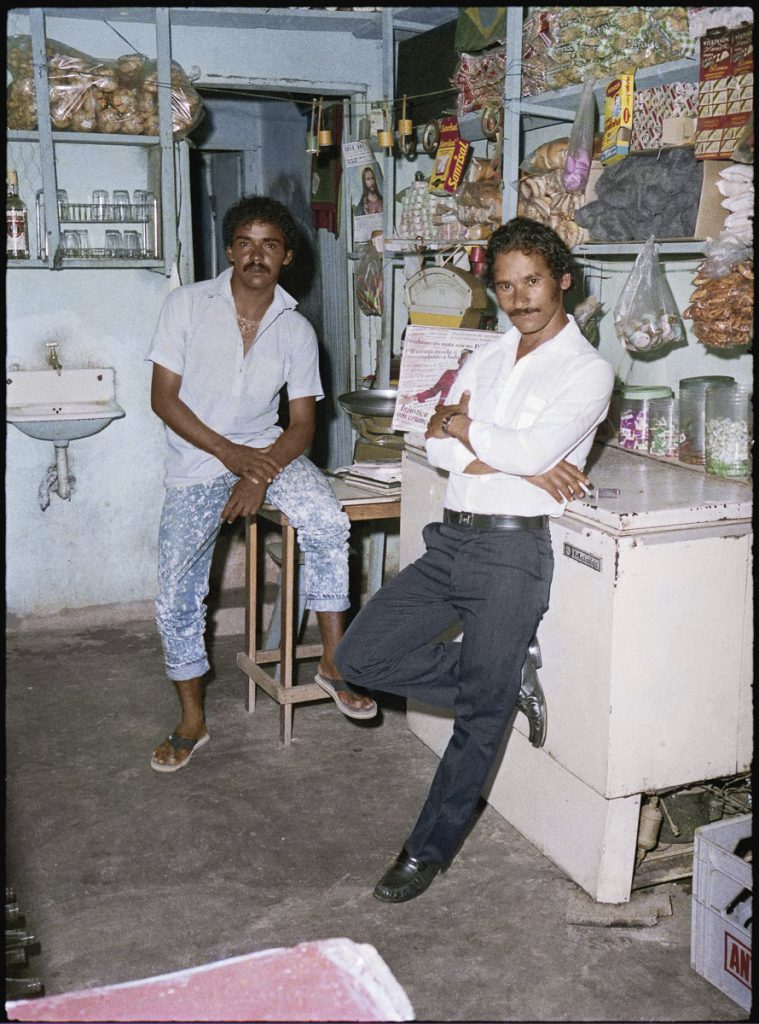

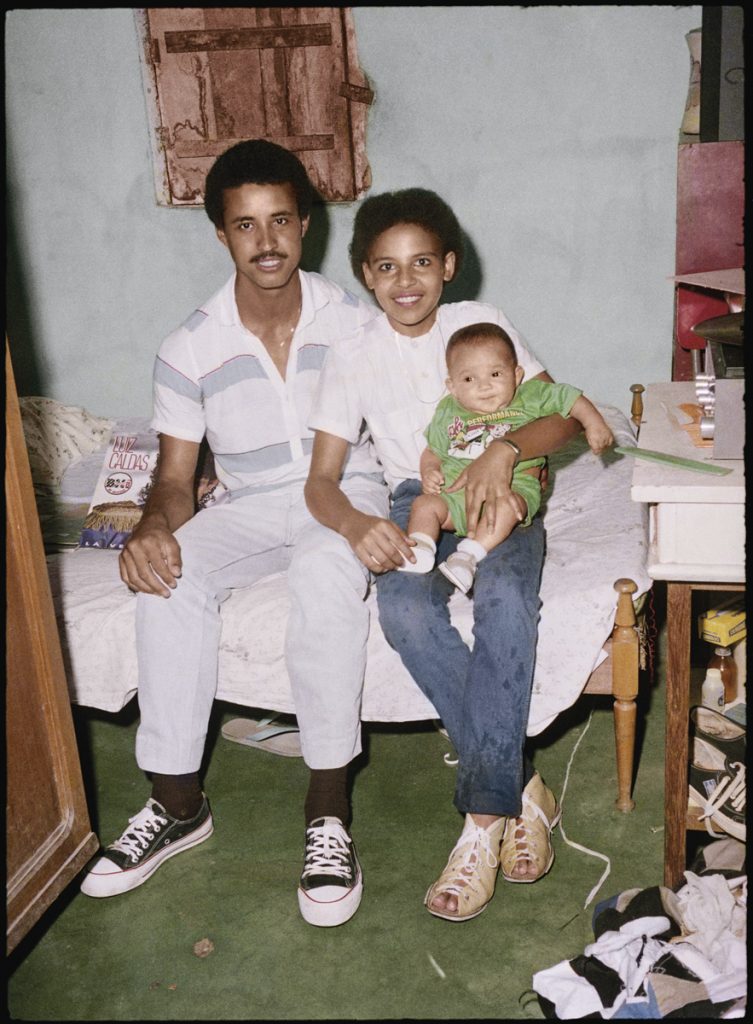

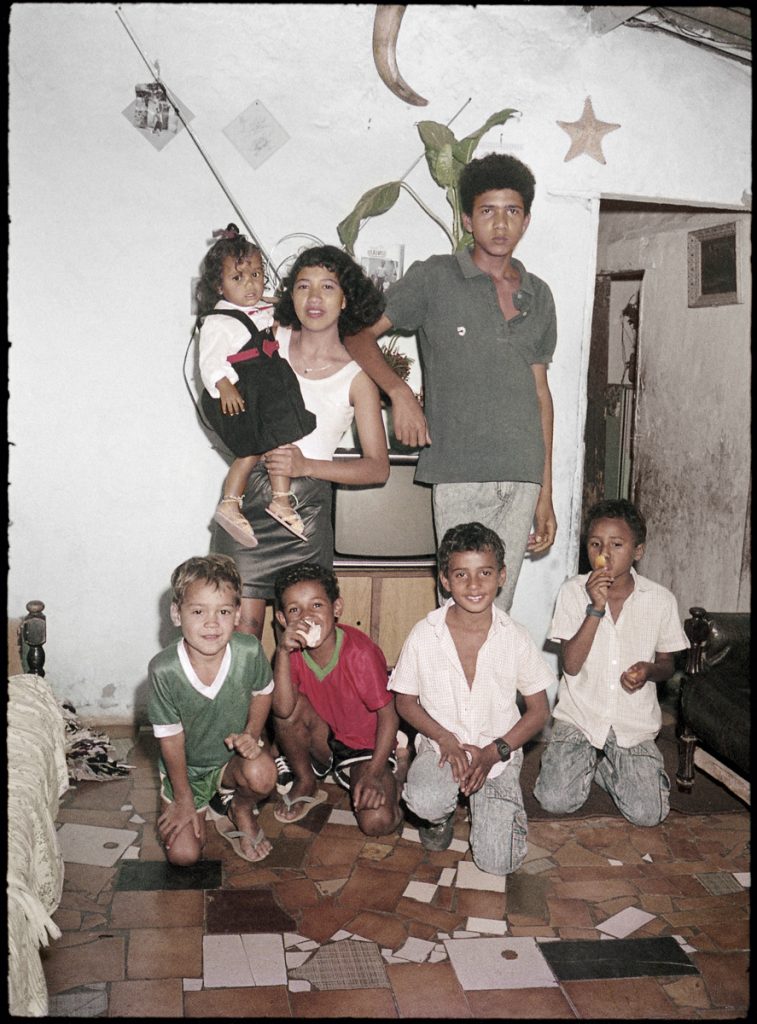

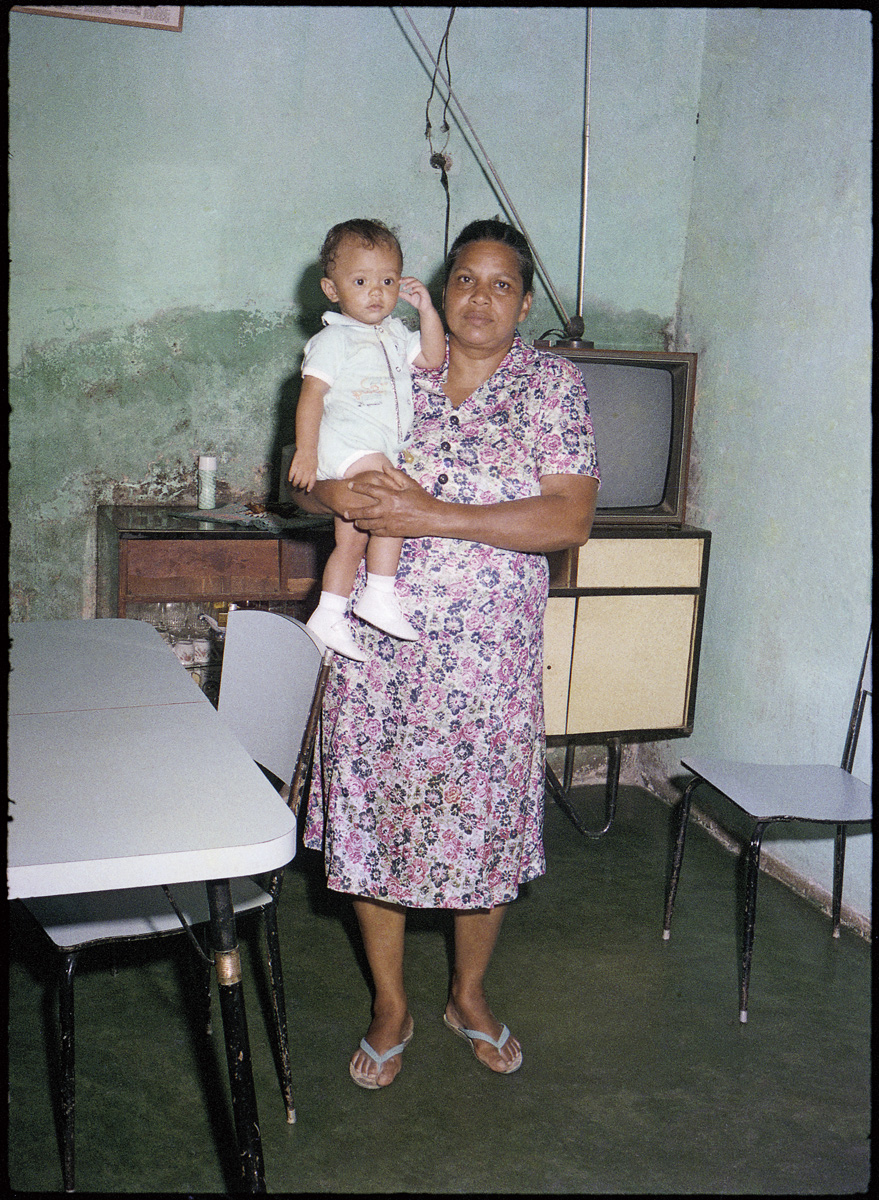

Publicado em: 20 de November de 2019Afonso Pimenta’s portraits of the inhabitants of the Aglomerado da Serra community in Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, taken in the 1980s fill a gap in the recent visual history of Brazil, a period when photography was still a privilege of the few. Now 64 years old, Afonso Adriano Pimenta has done a bit of everything. He has worked as a street sweeper, bricklayer, factory worker, nightclub doorman, and brothel guard, amongst other things. From the early 1980s he worked as a photographer, photographing celebrations and everyday scenes. Most of his work features the inhabitants of Aglomerado da Serra, one of the largest favelas in Brazil, in Belo Horizonte. Aglomerado da Serra (literally, “agglomeration on the hills”) consists of a number of different neighborhoods sprawling over 1,5 thousand square kilometers with 50,000 inhabitants, according to the city authorities.

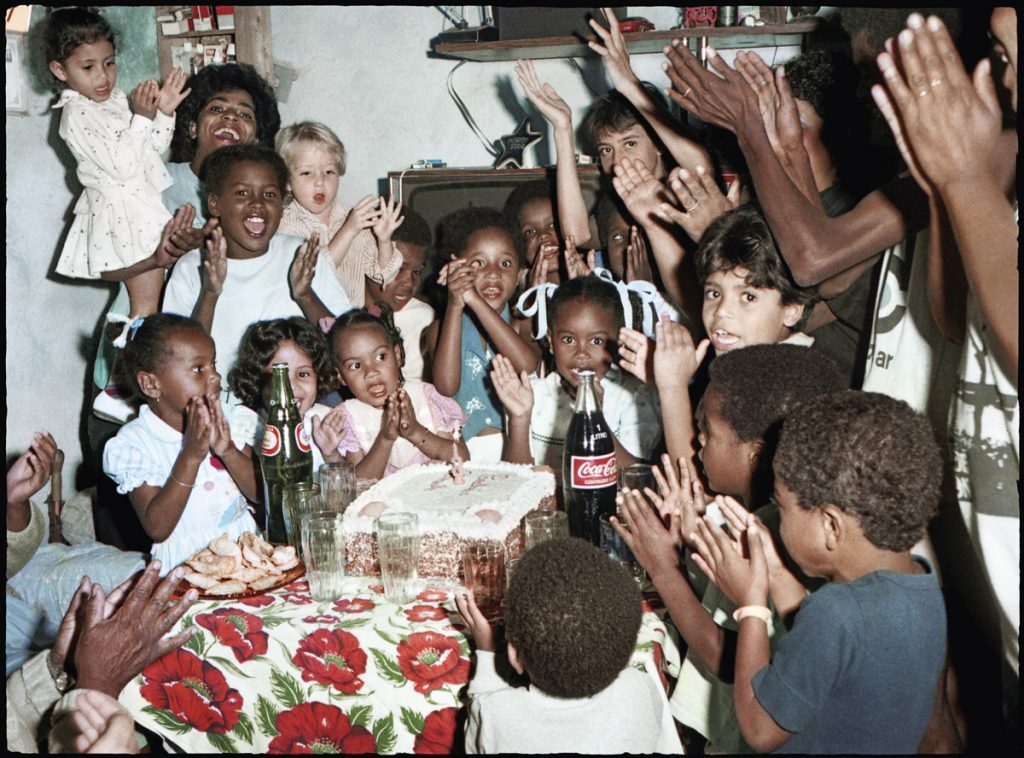

Afonso estimates that he has taken more than 300,000 photographs of the district, recording everything from children’s birthday parties to Black music in dance halls and raves. Many of them have been lost over time. The rest, about 80,000 images, were stored unseen at his home until 2015, when he joined the project Retratistas do morro [community portraitists], which was set up by the Minas Gerais visual artist and researcher Guilherme Cunha. Thanks to that project, Afonso’s photography is now to be seen in exhibitions in Belo Horizonte and in various cities in the state of São Paulo.

First contact

In 1963 Afonso moved from the small town of São Pedro de Suaçuí in rural Minas Gerais to the big city. His parents were farm workers who had raised a family of sixteen of their own children and another four orphans. “As there were so many of us at home, my mother asked my godmother, who lived in Aglomerado da Serra, if she could look after me.” On getting off the bus in Belo Horizonte aged nine, he was enchanted by the lights and bustle.

At his godmother’s house, though, he slept in a little backroom and had to work harder than in the countryside. One of his jobs was to prepare manure to sell in the wealthier parts of the neighborhood. With no piped water in the district, a problem faced by most of the neighbors, he had to go to the well three kilometers from the house. A small boy, he couldn’t manage to carry a full can on his head, so he had to make the trip several times each day.

Afonso first tried his hand at photography as a teenager. One of his fellow students at night school owned a Kodak Instamatic 11. The simple camera was coveted at a time when photography was a luxury. “Anyone who had a camera was king,” explains Afonso. “One day, the guy opened the back of the camera and showed me how the diaphragm worked, which I thought was amazing.”

Afonso never managed to buy the camera from his colleague, however much he longed for it. At the time, he was making a living selling cardboard for recycling. A little later, in 1969, he started to work as a landscaper for the local council. He had his photograph taken for the first time when he was fourteen and needed the photo for his job applications.

In 1971, when he had been promoted to street cleaner, he became friendly with Mrs Inês, a neighbor in Aglomerado. “She was my second mother, she cared for me, gave me food and did my laundry.” Concerned about the bad company the boy kept, the matriarch decided to recommend him as an assistant to her son, the photographer João Mendes, who remains the owner of the photographic studio Foto Mendes in the Serra, a middle-class neighborhood which gave its name to the Aglomerado, to this day.

Comings and goings

Afonso’s eyes shone when he heard the word “photographer.” He started by developing 3 × 4 identify photographs, the mainstay of João’s small business. The boy had no experience whatsoever in photography – “just a lot of curiosity” – but rapidly became interested in cameras and the chemical processes involved in developing. “The features would start appearing little by little, the first to emerge was the nose.”

When the shop was quiet, Afonso, who divided his time between his job as a street cleaner with his apprenticeship at the photographers’, would study the cameras. He found out so much about them that he ended up being chosen by his boss to take photos on his own at a wedding in the suburbs of Belo Horizonte. With a 35mm hanging from his neck, he felt like a celebrity.

Afonso was working with João when his restlessness and desire to improve his life set him on the road, in the company of one of his brothers. In 1976 he started working on infrastructure projects around Brazil. Amongst the projects he worked on were the Itaipu dam in Paraná and the Angra 1 nuclear reactor on the coast of Rio de Janeiro state. As a contract worker for the big construction companies, he worked in Iraq, Angola and Kenya. In his spare time, he would write letters for his illiterate colleagues send to their families, photograph the workers with his own camera or offer to take them with other people’s cameras.

He had another reason for his frequent trips. Having studied the martial arts since he was a teenager, Afonso started taking part in Shotokan karate competitions. He visited almost twenty countries to compete, including the USA, Mexico, and Ireland – where he ended up living for a few months. His athletic build and Afro hairstyle won him the nickname “Lion.”

Enjoying life

When he tired of travelling, Afonso returned to Belo Horizonte and started working with João again. In total, they stayed together for more than a decade – from 1971 to 1982. As well as taking their 3 × 4 identity photos, João was hired by the inhabitants of the Aglomerado to photograph their baptisms, graduation ceremonies, and weddings. This work outside the studio was a godsend to Afonso, who, as time passed, started to find the routine studio work boring.

At the beginning of the 1980s, João opened a branch of Foto Mendes in Aglomerado da Serra and appointed his assistant as manager. That was when Misael Avelino dos Santos, one of a group which had set up Rádio Favela, a community radio station known as the “Voice of the Hill” because of its work supporting the inhabitants, came by the shop looking for someone to photograph the anniversary of one of the Black music parties, which the radio station advertised in the city.

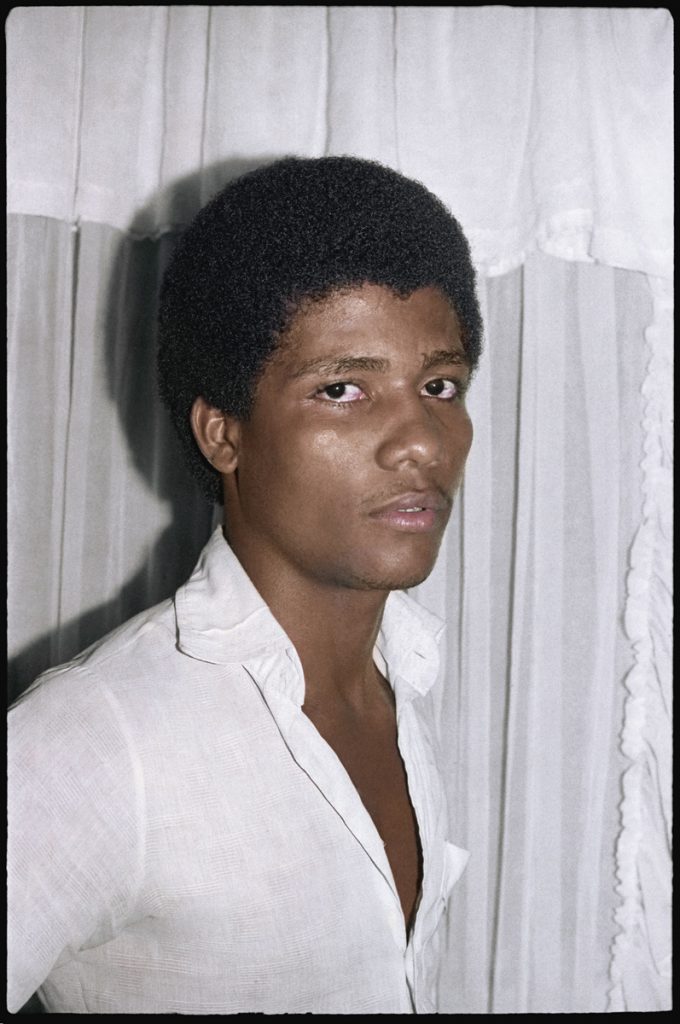

Afonso took on the job without knowing that he was sealing his fate as a photographer. The Black music parties had taken off in Belo Horizonte in the early 1970s, attracting large numbers of young people from the poorer areas of the city. “There wasn’t much for us to do, so those parties were our chance to have some fun,” sums up the 52 year old artist and craftsman Rení Cândido da Silva, who lives in the Aglomerado.

Afonso started going regularly to the parties. One of them was a regular party on the street that gave access to the Aglomerado. Another was organized away from the favela, at the PUC Minas Gerais Students’ Union, between the Serra and Funcionários middleclass districts in the south of the city. The student militants opened the doors of the big hall to the public, mainly black and poor. Afonso also frequented the party Italiana, in the center of the city. Many couples got together at the events, dancing cheek to cheek by the end of the night. “I ended up photographing some of their weddings,” he says.

Despite their success, the parties, with music of stars such as James Brown and KC & the Sunshine Band on the dance floor, were fiercely repressed by the police. Brazil was living under the yoke of the military dictatorship and large gatherings were seen as a problem by the regime. “And there was racism as well, which until today associates Black people with hooliganism,” adds Misael. As in other cities, it was not uncommon for the police to raid the parties and arrest those present. For Misael, the brutality was responsible for emptying the parties, which began to go out of fashion at the end of the 1980s.

Between 1984 and 1989, Afonso followed a routine: photographing the parties on Saturdays and Sundays, developing the films and, the following weekend, offering the 9 × 12cm portraits to the patrons. He rapidly added other parties to his routine. He estimates that he took more than 100,000 images during the five years, many of which have been lost. This was the way he started to live through photography and document a story: “Ours, the story of the favelado. And with great dignity for that matter,” praises Misael.

In fact, it was a story that has been little documented, and not only by photography, recalls the Minas Gerais filmmaker and researcher Joel Zito Araújo. “Even nowadays, the people that Afonso photographed are not seen as part of the ideal Brazil desired by our elite. On the contrary, they symbolize the poor, who should disappear from the map.”

After growing up in Rio de Janeiro, Joel Zito lived his first years as an adult in Belo Horizonte, between 1975 and 1984. “What the images show is the Black pride of poorer people whose idea of their own blackness came through mass culture, such as Michael Jackson’s music or Blaxploitation movies and TV series.

Perfect framing

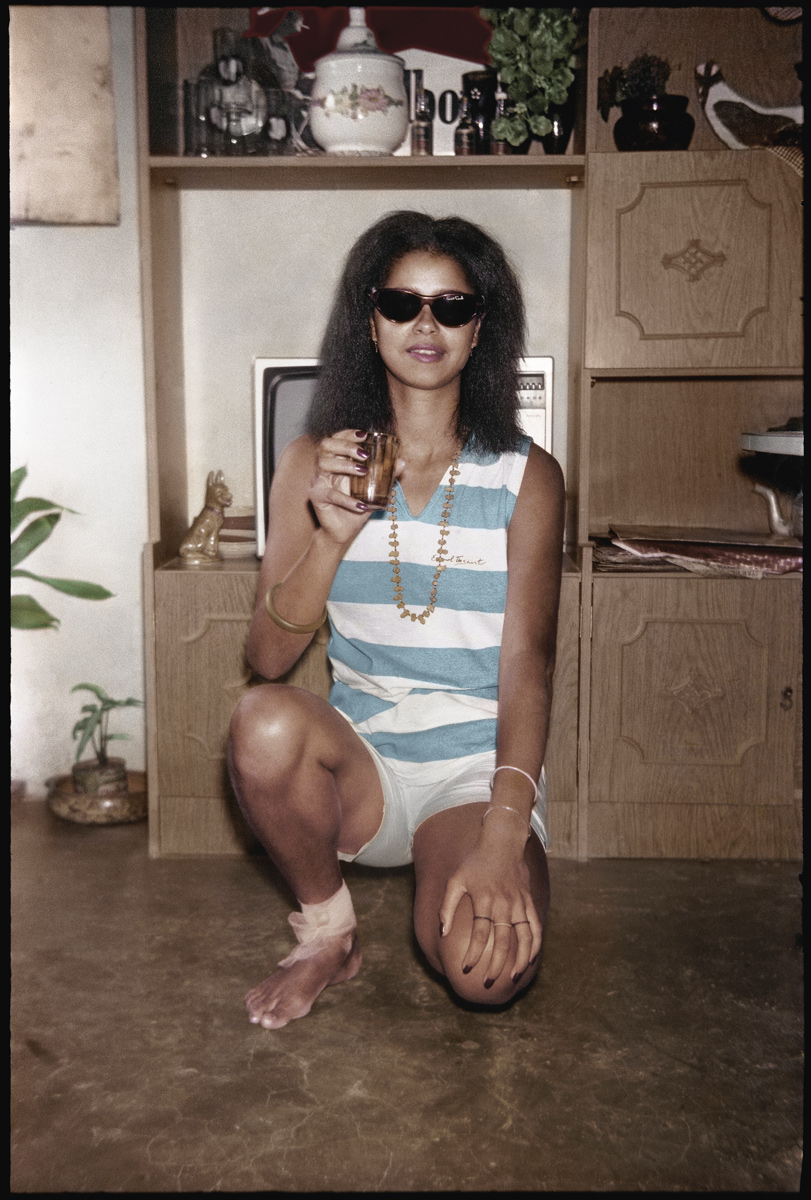

The black music parties opened the doors for Afonso to start photographing the homelife and relatives of the party-goers. Pleased with the impact of his photos, he started approaching people directly. “It’s when you go to the client, and don’t wait for him to come to you.” In the 1980s and 90s, he would walk through Aglomerado da Serra during the week with his 35mm camera, and sometimes on Saturdays. “It was an event,” recalls Marcilene da Conceição Dionysius do Amaral, a 55-year-old carer for the elderly. “Everybody would tidy themselves up at home, waiting for him to pass by.”

Anything and everything served as a pretext to invite the photographer in: new clothes, the birth of a child, a desire to show relatives their life in the big city. With the insight of a local, Afonso would frame his subjects perfectly. He often included consumer goods in the frame – such as a TV, a music player or boombox, or even a ventilator. “Everyone wanted to show off their material success. The objects were trophies.”

With an average of thirty clients a day, Afonso did not avoid challenges. When the client’s house was too small, he would photograph them in the yard or on the roof, with a view of the city in the background. Even the alleys could be pressed into service, like when he photographed a bride, whose appearance drew curious neighbors. When he heard that there hadn’t been a photographer at the wedding, Afonso would insist that the bride put on her white dress again so he could photograph her, even days later.

The local bars were also the scene of some of his photographs. “Sometimes I would be passing in the street and someone would call me over to take a photo of a pool game,” he recalls. He never refused work, not even from those involved in “the movement,” as drug trafficking is known. “I photographed everything, even bodies at funerals, but I never wanted to photograph naked women.”

When he started working door-to-door, Afonso had about fifteen competitors in Aglomerado, but through his creativity he managed to conquer his rivals. When he photographed an engaged couple, for example, he would hide a lamp in the floral arrangement. He also used professional filters such as a cross screen, and others which he improvised from PVC pipes and glass. Using this paraphernalia, he could simulate lighting effects in his images.

Self-taught, Afonso says that his main influence was his friend João Mendes, who taught him both the techniques and how to behave – one of his rules was that the photographer should never mix with the guests at a party. Another of his references is Câncio de Oliveira, whose scenes of Belo Horizonte in the 1940s appeared in the picture postcards commonly found in book- shops and stationers at the time.

No image

In looking back at her life, 35-year-old salesperson Renata Gonçalves dos Santos recalls that Afonso photographed almost all of it. Everything is in her photograph albums, from the first photograph taken when she was one year old, to her high school graduation, with her birthday parties as a child, her first Eucharist and confirmation in between. “When I get married, I want Afonso there to photograph the ceremony.”

Afonso’s images also populate the memory of thirty-year-old manicurist Daiane Cristina Oliveira. Some of the few photographs of her as a child show his mark. “My mother was a cleaner and had no money to buy a camera. Sometimes we didn’t have money even to buy a photograph from Afonso.” Until today she resents not having images of the first months of her life.

In “The Missing Image,” the Rio filmmaker Yasmin Thayná writes about the scarcity of photographic records of the black population in Brazil. Many of her friends, of African descent like her, do not have photos of when they were children. “In general, their first image is for a document, such as a student ID or Civil ID,” she notes. “It is an official image, not personal.” To Thayná, the absence of such images hides the oceanic depths of social inequality. “Who could take photographs in the past, and we are talking about up to the 1990s, were people who had the money to buy a camera and film, as well as affording to get them developed.”

Still in the fight

Afonso still doesn’t rest. He reckons that the cell phone has taken about 30% of his clients but, even so, every Saturday he leaves his house in Céu Azul in the Pampulha district. His destination is Aglomerado da Serra, his HQ on the other side of the city, where he still photographs debutante balls and marriages. When there is too much work, he usually takes his son Keny with him. Keny is the only one of fourteen children, the fruit of nine relationships, who follows his father’s footsteps.

Even retired, he still needs to work to help Keny and his youngest daughter, Kait, 23 years old and studying at college. To make ends meet, he still teaches martial arts and works as a masseur, as well as accepting commissions for painted portraits. Like so many other Brazilians, he continues working at anything that comes along. But photography is his true profession. ///

+ Retratistas do Morro: preservação da memória visual do Aglomerado da Serra [Community portraitists: preserving the visual memory of Aglomerado da Serra], curated by Guilherme Cunha, see www.facebook.com/retratistasdomorro/

Tags: Retratos